International

Labour Organization

Your health and safety at work

CONTROLLING HAZARDS

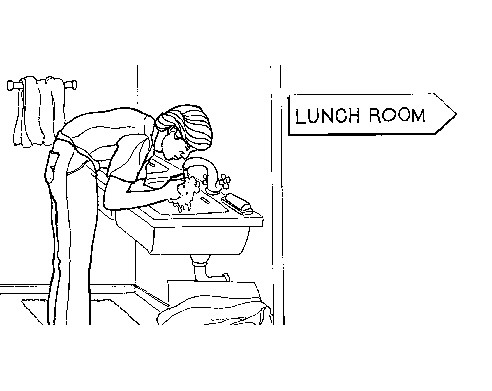

Finally, personal hygiene (cleanliness) is also very important as a method of controlling hazards. Your employer should provide facilities so you can wash and/or take a shower every day at the end of your shift, no matter what your job is. Wash your skin and hair with a mild soap, rinse and dry your skin completely to protect it. Washing hands regularly, and eating and smoking away from your work area help to prevent ingesting contaminants.

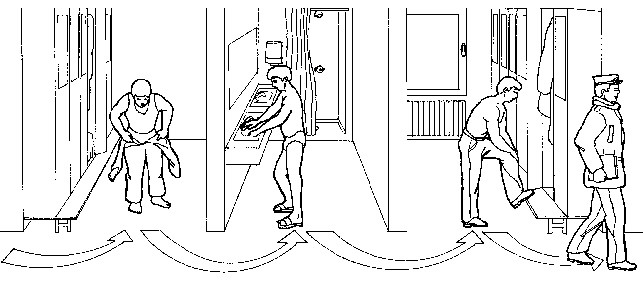

Do not take workplace hazards home with you! |

|

Lack of personal cleanliness can affect your family's health.

Your family can be exposed to the hazards you work with if you bring chemicals and other workplace contaminants home with you on your clothes, hair or skin. Before you leave work, wash/shower and change your clothes when necessary to prevent bringing workplace contaminants home. Leave your dirty clothes at work or, if you must wash them at home, wash them separately — not with the family wash.

Personal hygiene is very important in terms of reducing health hazards. Dirty clothes can spread hazardous substances to your family. |

|

It may seem that the amount of contaminant you can bring home on your clothes or skin is very small and cannot hurt your family. In reality a small exposure every day for months can add up to a big exposure. A classic example of this “spreading the hazard” involves asbestos, where wives of asbestos workers have developed asbestosis from exposure to the asbestos on their husbands' work clothes. Similarly, children have developed lead poisoning from exposure to lead which comes home on their parents' work clothes.

If you wear protective clothing at work, such as aprons, laboratory coats, overalls, etc., these should be cleaned regularly and you should inspect them for holes or areas that are worn out. Workers who launder these clothes should be trained in the types of hazards they may work with and how they can be controlled. Inspect your underclothes at home for any signs of contamination with oils, solvents, etc. If you find any signs, then it means your protective clothing at work is not effective. Use section VI, Personal hygiene in the Check-list on control methods at the back of this Module for some reminders on personal hygiene at work.

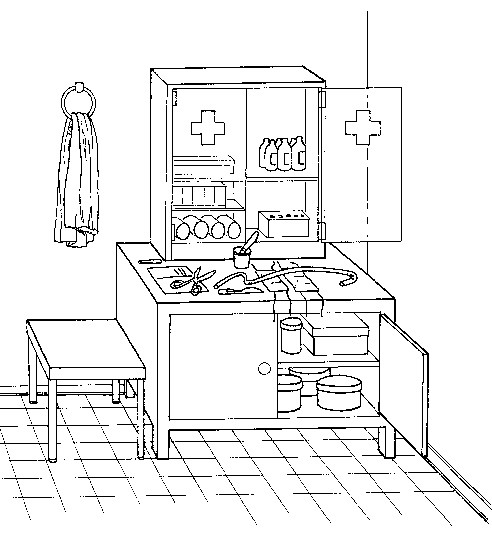

Every workplace should have some kind of first-aid facility

Every workplace should have at least minimal first-aid facilities as well as adequate personnel trained to provide first aid. First-aid facilities and trained personnel are important components of a healthy and safe workplace.

A basic first-aid facility |

|

Does your workplace have at least basic first-aid facilities? See Appendix IV at the back of this Module for some basic information on what a minimum first-aid station should include. Use section VII, First-Aid and fire-fighting equipment in the Check-list on control methods at the back of this Module to help you assess first-aid and fire-fighting facilities in your workplace.

|

Points to remember about general cleanliness and personal hygiene |

|

|

III. Choosing methods of control

If you cannot completely eliminate a hazard, then use a combination of control methods to protect workers from being exposed to occupational hazards. No one method of control can protect you completely from hazards. When you are choosing methods of control, it is important to consider how workers are likely to be exposed to the hazard: whether the hazardous agent can be inhaled, absorbed through the skin, ingested, or whether it can cause immediate injury. This information will help you to decide what protections are necessary.

Finally, the atmosphere in the workplace must be monitored (checked) regularly for levels of hazardous materials. Knowing what the levels of contaminants are in the air, for example, will help you decide on the best methods of control for those contaminants at those levels. Health and safety representatives must always check on the operating systems in the workplace — do not assume that a new exhaust ventilation system will work forever: filters get blocked, fans lose their efficiency, etc. Always look for signs of hazards, such as the smell of fumes, lack of ventilation, etc. All safety equipment should be serviced frequently and have its level of efficiency checked. Use section VIII, Methods of control in the Check-list on control methods at the back of this Module to help you assess control measures in your workplace.

Which control method to use? |

|

|

Points to remember about choosing a method of control |

|

|

IV. Role of the health and safety representative

Your role is to work proactively (to take action before hazards become a problem) to prevent workers from occupational exposure by making sure hazards are controlled and kept under control. The control methods discussed in this Module are the most important means of protecting your health and your co-workers' health at work. Use section VIII, Methods of control in the Check-list on control methods at the back of this Module to help you assess hazard controls in your workplace. You can use that information in working with your union and employer to solve problems with hazards in the workplace. Other steps to help you reach your goals are:

Safety representative |

|

Work with the union and the employer to eliminate hazards wherever possible. If new work processes are being discussed, or equipment purchases are being planned, try to get agreement from the employer to place safety as a priority in the planning process. For example, only machines that meet national or internationally recognized safety standards should be purchased. Similarly, if a chemical has been banned or severely restricted by any government, it should not be used. When hazards cannot be eliminated, then a combination of control methods is the best way to prevent exposure.

If you are looking for “safer” substitute chemicals, try to find out whether the proposed substitute chemicals really are safer. Try to get information on substitute chemicals from: your employer, the chemical manufacturer, your union, local factory or labour inspectorate, local colleges or universities, the local fire department, your local library, ITSs (International Trade Secretariats) or the ILO (International Labour Office).

It is best to enclose all toxic materials or work processes using toxic materials. However, since this is often not possible, try to get the employer to enclose at least all highly toxic materials.

When using administrative controls, it is important that employers use other protective measures at the same time to prevent exposing workers to hazards. Administrative controls only reduce the amount of time you are exposed — they do not eliminate exposures.

PPE is the least effective method of hazard control and should be used only when hazards cannot be controlled sufficiently by other methods. Before requiring the use of PPE, the employer should demonstrate to the union that he or she has tried to control hazards with engineering controls, but was not able to reduce exposures to “safe” levels. Try to get agreement from the employer to implement effective engineering controls and eliminate the need for PPE by a specified date. PPE should always be used together with other control measures.

Remember that the effectiveness of some PPE decreases in hot, humid working conditions.

When purchasing PPE, try to get items that have been designed in accordance with recognized standards set by relevant institutions. Also, try to get the employer to purchase protective clothing in sizes to fit the workers who will wear the PPE.

Workers who must use PPE should be trained before using the equipment and should receive refresher training at least once a year. Workers using PPE should participate in a company-sponsored medical surveillance programme (if the employer will not provide this then the union may want to sponsor such a programme).

Washing/toilet facilities should be a priority among union demands for a healthier and safer working environment. It is possible to provide adequate washing/toilet facilities for a minimum cost. Workers should be encouraged to wash/shower regularly, not only when they think they may be contaminated.

Try to get your employer to provide laundry facilities so that workers do not have to launder their work clothes at home. Workers should be educated about the importance of washing work clothes separately — not with the family's clothes. This is particularly important if workers receive laundry money from the employer.

First-aid facilities and adequate personnel trained in first aid should be a priority among union demands for a healthier and safer working environment.

Workers should be provided with eating and break areas away from their work areas to prevent ingesting hazards and for a more pleasant work environment.

Work with the union and employer to make sure the atmosphere in the workplace is monitored regularly for levels of hazardous materials. If the employer or union does not have personnel trained in monitoring, then the local factory inspectorate may be able to help you.

|

Controlling occupational hazards is the best way to protect workers from exposures. Occupational hazards can be controlled using a number of strategies. All of the control methods described in this Module are based on the same idea: workers should not be exposed to workplace hazards. Some control methods are better than others, but no single method of control can completely protect workers from hazards. If a hazard cannot be completely eliminated, then a combination of methods should be used to reduce hazards to “safe” levels (levels that will not place workers' health at risk). Some methods of control cost less than others but may not reduce hazards effectively. The responsibility for preventing exposure is often placed on workers, requiring them to wear protective clothing, which is usually very uncomfortable in the hot and humid conditions that exist in many workplaces. Personal protective equipment, such as respirators, protective suits and ear muffs, should be thought of as providing a back-up for other techniques that are designed to control hazards at the source. There are a number of actions mentioned in this Module that you and your union can take toward controlling hazards in your workplace. |

Exercise 1. Machine-guarding case-study

|

Source: This material is taken from Making Your Illness/Injuri Program Work, produced by the UCLA - LOSH Program, 1001 Gayley Avenue, Los Angeles, Cal. 90024, U.S.A. Note to the instructor For this exercise, you will need to give each trainee or group of trainees a copy of the case-study and the questions. The list of answers are for you to use with the class. If you cannot make copies, then read the case-study to the class and allow trainees to discuss the questions in small groups. The purpose of this exercise is to give the participants in your class a chance to evaluate and discuss an occupational accident that could have been prevented with proper control methods and training, and to discuss machine guarding in the participants' workplaces. You can change the names of the people in the case-study to common names in your region if you like. Instructions Trainees should work in small groups of three to five people. Ask them to read and discuss the case-study with their group, then answer the questions together with their group. Discuss the groups' answers with the whole class. Case-study (This accident is based on a real work-related death. Only the names and dates have been changed.) On August 16, 1986, Juan Espinosa was assigned to work as an operator on a steel-slitting machine at ABC Steel. Juan was killed on his first day operating the machine, which was also his first day working at ABC Steel. The machine The steel slitter is a machine that cuts rolls of steel into strips. The steel rolls off a roller, is cut into strands, and wound up again by a recoiler. The strands of steel on the outside of the roller must stay taut (tight). Workers in the factory did not use the tension stand that was available to keep the steel taut — instead they inserted pieces of cardboard by hand into the pinch-point of the recoiler. (The pinch-point is the place where the flat steel coming out of the slitter meets the rolling recoiler that rewinds the steel.) This kept the steel taut but was a very dangerous practice. Workers were able to do this because there were no guards on the machine. The company knew the use of cardboard was unsafe, yet they allowed workers to do it because it was quicker and more economical. Training Usually a worker assigned to his job was given 30 days of training. Juan Espinosa did not receive any training at all before his first day operating the steel slitter. Safety meetings were held approximately every three months but the content of the meetings was generally not communicated to the workers. Events leading up to the accident On the day of the accident, slitter helper John Doe was told to work with Juan Espinosa throughout the evening shift. Espinosa only spoke Spanish. Doe only spoke English. After five hours of work, Doe went to another section of the plant to get another coil of steel. As he did this, he heard an unusual noise from the machine. He ran back to the recoiler and saw Espinosa wrapped in it, dead, with approximately 12 sheets of steel on top of him. Doe ran to the emergency stop button which was approximately three metres away from the machine. Espinosa was caught in the recoiler while inserting cardboard to keep the steel taut. He was killed instantly. |

Questions

| 1. What do you think were the factors that caused this accident? | Answer |

| 2. How could this accident have been prevented? | Answer |

| 3. Do machines in your workplace have guards on them? | |

| 4. Are there any problems with machine guards in your workplace (for example, do the guards cause you discomfort when you do your job, do they slow you down, etc.)? | |

| 5. Are you familiar with the machine-guarding regulations for your region or country? Do the regulations apply to the machine(s) that you operate? (If your country does not have guarding regulations, work with your union to press the government to develop regulations.) | |

| 6. What actions can you take to make sure machines in your workplace are properly guarded? |

Exercise 2. Control methods

|

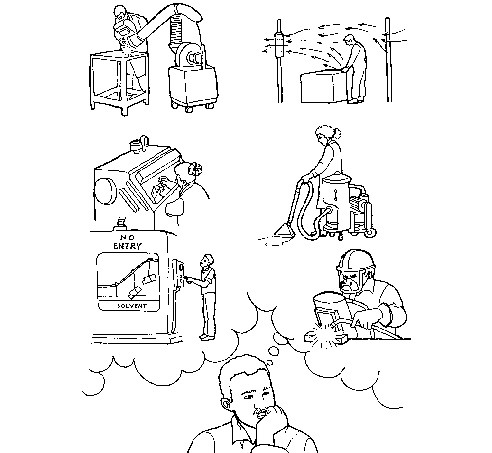

Note to the instructor For this exercise, you will need enough copies of the pictures in the exercise so that each trainee or group of trainees can see them easily. If the class is small, you can just hold the pictures up in front of the class. You will also need a flipchart (or some large pieces of paper taped to the wall) and markers or a chalkboard and pieces of chalk. Use this exercise to get the class participants involved in identifying problems and suggesting solutions related to the topics discussed in this Module. These pictures and the discussions you stimulate will reinforce what you have taught in this Module. Instructions Show each picture to the whole class and ask the questions in the text or questions of your own. When you ask questions, wait several seconds for a response from the trainees. If no one responds, then you can prompt with the responses given below. Write the trainees' responses on the flipchart or chalkboard. Mark a line down the middle with “PROBLEMS” written on one side and “SOLUTIONS” on the other. Write the trainees' responses in the appropriate columns. |

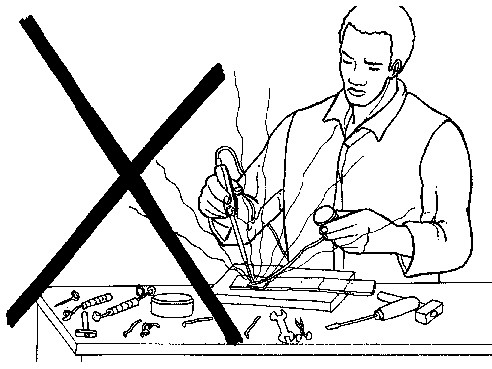

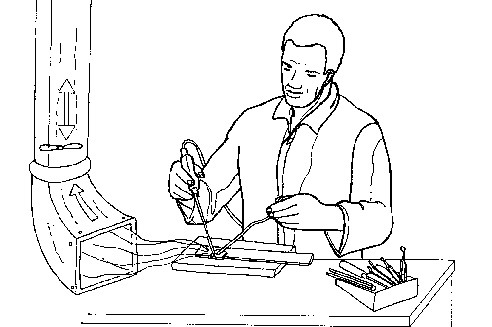

1. A worker soldering in a dirty shop without ventilation and with no PPE. |

|

| Question: What is wrong with this picture? What is missing? How will this situation lead to this worker being exposed to the lead used in the soldering process? Could this situation also cause his family to be exposed to lead? How? What suggestions can you make to prevent this situation? | Answer |

Picture of local exhaust ventilation system while the same worker is soldering. |

|

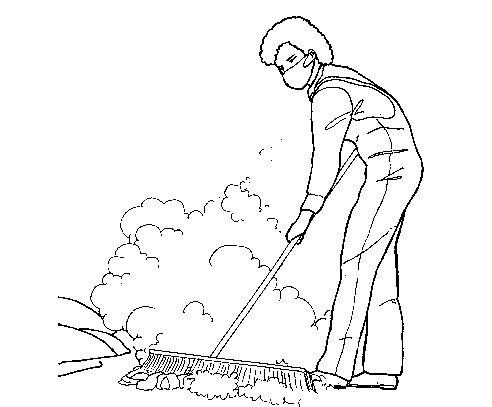

2. A worker dry sweeping dust from soldering area. |

|

| Question: What is wrong with this picture? | Answer |

Picture shows a worker cleaning up the worksite with an industrial vacuum cleaner. |

|

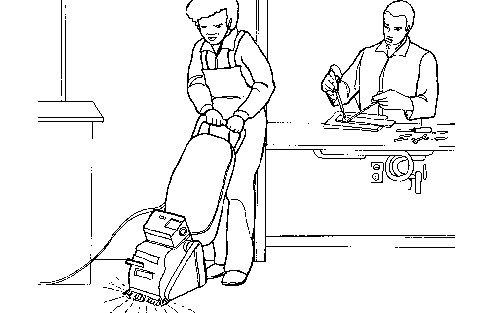

3. A worker eating something in the work area. |

|

| Question: What is wrong with this picture? | Answer |

Picture shows a worker washing his hands. There are clean towels, and a lunch room sign. |

|

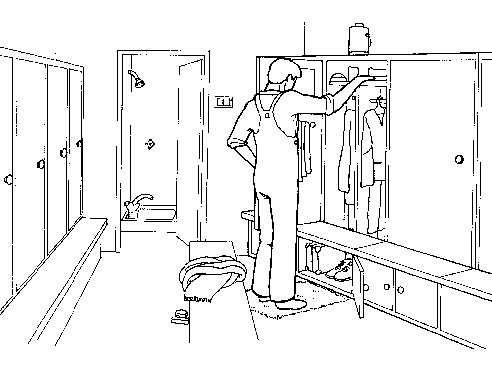

4. Picture shows shower and locker areas. |

|

| Question: Why should employers provide shower and locker areas? | Answer |

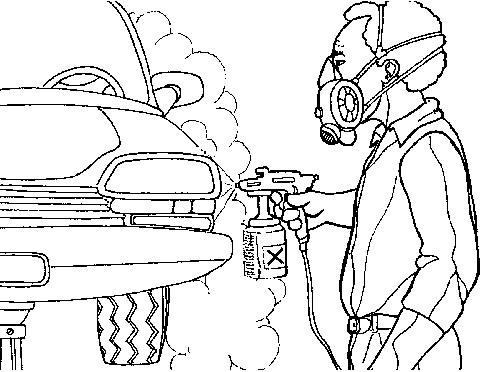

Picture shows a worker wearing a cartridge respirator while working around dusts. |

|

| Question: Will this respirator prevent the worker from breathing in dusts or other hazardous substances? | Answer |

(Note to instructor: If you can get a cartridge respirator and a paper mask to show the trainees, pass them around to show the difference, then explain as follows: one method of preventing inhalation of hazardous substances is to use respirators, although this is not the best method of prevention. A paper mask does not fit tightly against the face and will not prevent the worker from inhaling gases, vapours or even dusts. A paper mask can be used for occasional exposure to non-toxic dust when the dust concentration is low. The cartridge respirator is needed for working around gases or vapours but the type of cartridge you need to use depends on the substances with which you are working.)

|

Note to the instructor Give the trainees a copy each of this check-list for use in their own workplaces. I. Machine guards When evaluating your workplace for proper guarding, check for the following: |

| 1. Are the operators' hands, fingers and bodies kept safely away from the danger areas when a machine is being operated? If no, what type of guard could be installed? | ||

| 2. Are starting and stopping controls within easy reach of the operator? | ||

| 3. Are belts, pulleys, chains, sprockets, gears and blades properly guarded? | ||

| 4. Are rotating parts covered or out of reach inside the equipment? | ||

| 5. Are fans that are located near the floor guarded? | ||

| 6. Are guards firmly attached so they cannot easily be removed? | ||

| 7. Have operators been trained in the importance of using guards? Have they been trained in the operation and maintenance of guarded machines? | ||

| 8. If operators are not within sight or hearing distance of other workers, is an alarm device provided in case of an accident? | ||

| 9. Is there an effective system for disconnecting and locking out the machine from its power sources when guards are removed during maintenance? Have workers been trained in lockout procedures and in machine maintenance procedures? | ||

| 10. Do machine guards restrict workers' productivity, cause discomfort or annoyance to the operator? | ||

| 11. Does the design or construction of the machine guards create any new dangers? | ||

| 12. Is the company following all local or national requirements for machine guarding and any special rules for guarding of hand and portable powered tools and laundry machinery? |

| Use the following questions to help you when evaluating a local exhaust ventilation system in your workplace. |

| 1. Do you smell chemical odours or see dust building up near the hood or machines? Can you see contaminants in the air? | ||

| 2. Is the hood close enough to the place where air contaminants are being released? | ||

| 3. Are the ducts plugged? When you tap a duct, it should sound hollow; a “thud” may mean it is plugged. Are filters clogged? | ||

| 4. Are any ducts broken or leaking? | ||

| 5. Check motors and fans. Are any belts broken? Are fans installed correctly (not backwards)? Are fan blades covered with dirt, grease, etc. and inefficient? | ||

| 6. Ask your employer to show you the original design of the system. Have extra hoods been added to cover new machines? If any were added, was the system balanced again? Can it handle the new load? | ||

| 7. Are cross-draughts present that could carry contaminants away from the hood opening? Could the operation be enclosed with shields or booths to prevent draughts? | ||

| 8. Are there many bends, twists or Ys in the duct system? These can slow down the movement of the exhaust air as well as causing increased noise levels. | ||

| 9. Does the hood pull contaminants in the proper direction away from the worker's face rather than past it? | ||

| 10. Does the amount of clean air brought into the system equal the amount exhausted? If you have trouble opening doors because of “negative pressure”, this may be an indication that more fresh air is needed. | ||

| 11. Has the employer used an instrument called a velometer to see if the airflow is strong enough? | ||

| 12. To be sure the exhaust system is protecting workers, ask your employer to show you monitoring measurements of the levels of chemicals or other hazardous materials in the air. A ventilation system is only useful if it works and if it protects workers. |

III. Personal protective equipment

| Use the following questions when evaluating PPE if it must be used in your workplace. |

| 1. Has all protective clothing (masks, helmets, gloves, eye protectors, overalls, boots, aprons, etc.) been personally fitted and issued? | ||

| 2. Are protective clothing items immediately replaced when damaged or lost? | ||

| 3. Are protective clothing and equipment of good quality and the correct type for the job being done? For example, are eye goggles the correct type for the hazards? Some only offer protection against small flying particles, other types are required for protection against large particles or acid splashes. | ||

| 4. Are respirators handled carefully? Are masks personally fitted to ensure a proper seal? Is the type of respirator correct for the conditions (e.g. dust filters do not protect against gases or fumes; different canister and cartridge respirators are needed to neutralize different vapours and gases in the air)? Is there an independent air supply — either air-line or self-contained breathing apparatus for the most dangerous conditions? Have these been thoroughly checked and maintained (a failure to do so could result in death)? | ||

| 5. Have workers been properly trained in the use of PPE? Have workers and supervisors been trained in the use of filter, canister and air-bottle systems (they are only effective for limited periods of time)? Is the amount of time that workers are required to work in PPE limited to short periods? | ||

| 6. Is protective clothing (which can cause restrictive and oppressive working conditions) only worn for limited periods of time? Are jobs rotated to enable wearing the PPE for only short periods? | ||

| 7. Is all PPE provided to workers free of charge? | ||

| 8. Is PPE inspected, cleaned and maintained by management? Are workers expected to take contaminated clothing home? | ||

| 9. If the correct use of PPE affects bonus earnings, is the scheme altered to allow for this? | ||

| 10. Does the use of PPE create other risks, e.g. by reducing vision, mobility or hearing? | ||

| 11. Has the union been consulted about the purchase of PPE, and about setting up adequate systems for fitting, issuing, testing, maintenance, cleaning, replacement, training and supervision to ensure that equipment is effective? |

IV. Glove or respirator programme

| Use these questions to help you when assessing a glove or respirator programme. |

| 1. Ask for a meeting with management to learn all the details of the new programme. | ||

| 2. Request any sampling results that the employer has on exposure levels. | ||

| 3. Find out what the employer is doing to remove chemicals from the air or to prevent skin contact. | ||

| 4. Ask for a written plan showing how the employer will reduce or eliminate the need for wearing respirators or gloves in the future. | ||

| 5. Ask the employer to put a qualified person in charge of respirator and glove use. | ||

| 6. Ask what medical testing of workers will be done to ensure they are physically fit to work wearing a respirator. | ||

| 7. Make sure that medical testing will not be used to discriminate against workers who are experiencing lung problems caused by prior exposure to chemicals in the workplace. | ||

| 8. Request that several different sizes or brands are made available so each worker can choose one that fits well. | ||

| 9. Ask the employer to show the union any guidelines used for choosing the equipment. | ||

| 10. Are respirators approved by recognized standard-setting institutions? | ||

| 11. Ask for a union representative to be present at the training sessions for workers who will wear protective gear. |

| Use this check-list when assessing cleanliness and order in the workplace. |

| 1. Is the layout designed to facilitate order and cleanliness? Is there adequate space between machines? | ||

| 2. Are aisles, passageways, transport areas and exits clearly marked and free of obstacles? | ||

| 3. Are special areas set aside for storage of raw materials, finished products, tools and accessories? | ||

| 4. Are there racks for hand tools or other necessary items above work tables? | ||

| 5. Are there underbench slots or other spaces for storage of small personal belongings? | ||

| 6. Are receptacles for waste and debris in convenient locations? | ||

| 7. Are floor-covering materials suitable for the work and for cleaning? | ||

| 8. Are there screens or simple devices to prevent deposits of oil, liquid wastes or water on the floors? | ||

| 9. Are there drainage channels for waste water? | ||

| 10. Are there special groups of people to carry out day-to-day cleaning and weekly or monthly cleaning? | ||

| 11. Have arrangements been made to remove finished goods and wastes? | ||

| 12. Is there a clear assignment of duties for maintenance and repair of work premises, particularly stairs, walkways, walls, lights and toilet/washing facilities? |

| To practise good hygiene, remember to: |

| 1. Drink clean, potable water. | ||

| 2. Never eat in locker rooms, washrooms or where dangerous materials are used. | ||

| 3. Wash your hands and the exposed parts of your body regularly and take daily baths or showers. | ||

| 4. Clean your teeth and mouth daily and have periodic dental check-ups if possible. | ||

| 5. Wear proper clothing and footwear. | ||

| 6. Do not mix work and street clothes. | ||

| 7. Clean working clothes, towels, etc. with the help of a special laundry, if possible, particularly when they get contaminated. | ||

| 8. Keep physically healthy with regular exercise. |

VII. First-aid and fire-fighting equipment

| Use this check-list to help you assess the first-aid and fire-fighting equipment in your workplace. |

| 1. Is adequate first-aid equipment provided and checked regularly? | ||

| 2. Are trained and adequate first-aid personnel present during all shifts? | ||

| 3. Is adequate fire-fighting equipment provided? | ||

| 4. Is fire-fighting equipment maintained in a usable condition? | ||

| 5. Are locations of fire-fighting equipment posted? | ||

| 6. Have workers been trained in the use of fire-extinguishing equipment? | ||

| 7. Are emergency telephone numbers posted? |

| Use this check-list to help you evaluate the methods of control in your workplace. Before being satisfied with any methods of control, ask yourself the following questions: |

| 1. Does it adequately control the hazard? | ||

| 2. Does it allow workers to do their job comfortably without creating new hazards? | ||

| 3. Does it protect every worker who may be at risk of exposure to the hazard? | ||

| 4. Does it eliminate the hazard from the general environment as well as the workplace? | ||

| 5. Are less toxic chemicals used whenever possible? | ||

| 6. Are work processes used which minimize the release of gases, vapours, dusts or fumes? | ||

| 7. Are the sources of the release of gases or vapours completely enclosed? | ||

| 8. Are dust-producing machines or piles of dusty materials isolated or enclosed as much as possible? | ||

| 9. Are workstation locations chosen so that exposure to gases, vapours, dusts or fumes is minimal? |

IX. Labelling, information and emergency measures

| Use this check-list to help you assess whether chemical labels, information and emergency measures are adequate. |

| 1. Are containers with chemicals in them labelled indicating the contents and warning of the hazard? | ||

| 2. Is necessary information on safe handling and first-aid measures given on the label or as written instructions? | ||

| 3. Have workers been trained on health risks and safe handling of hazardous chemicals? | ||

| 4. Does training include information on safe storage and transportation of chemicals? | ||

| 5. Are emergency showers and eye-wash stations available at the worksite? |

Appendix I. List of extremely hazardous chemicals

Source: The WHO recommended classification of pesticides by hazard and Guidelines to classifications 1994-1995, International Programme on Chemical Safety, WHO/PCS/94•2, (Geneva, UNEP/ILO/WHO).

Entries and abbreviations used in the tables

The following notes apply to Table 1.

Status (Column 2):

ISO: Common name approved by the International Organization for Standardization. Such names are, when available, preferred by WHO to all other common names. However, attention is drawn to the fact that some of these names may not be acceptable for national use in some countries. If the letters ISO appear within parentheses, this indicates that ISO has standardized (or is in the process of standardizing) the name of the base, but not the name of the derivative listed in column 1. For example, fentin acetate (ISO) indicates that fentin is an ISO name, but fentin acetate is not.

N( ): Approved by a national ministry or other body, which is shown in the parentheses as follows:

A: United States Environmental Protection Agency or American National Standards Institute or the Weed Science Society of America or the Entomological Society of America;

B: British Standards Institution, or the British Pharmacopoeia Commission;

F: Association franšaise de Normalisation;

J: Japanese Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry;

U: Gosudarstvennyi Komitet Standartov, Russian Federation.

Main use (Column 3):

In most cases only a single use is given. This is only for identification purposes and does not exclude other uses.

| AC | acaricide |

| AP | aphicide |

| B | bacteriostat (soil) |

| FM | fumigant |

| F | fungicide, other than for seed treatment |

| FST | fungicide, for seed treatment |

| H | herbicide |

| I | insecticide |

| IGR | insect growth regulator |

| Ix | ixodicide (for tick control) |

| L | larvicide |

| M | molluscicide |

| MT | miticide |

| N | nematocide |

| O | other use for plant pathogens |

| PGR | plant growth regulator |

| R | rodenticide |

| RP() | repellent (species) |

| -S | applied to soil: not used with herbicides or plant growth regulators |

| SY | synergist |

Chemical type (Column 4):

Only a limited number of chemical types are shown. Most have some significance in the sense that they may have a common antidote or may be confused in the nomenclature with other chemical types, e.g. thiocarbamates are not cholinesterase inhibitors and do not have the same effects as carbamates.

| C | carbamate |

| CNP | chloronitrophenol derivative |

| OC | organochlorine compound |

| OM | organomercury compound |

| OP | organophosporus compound |

| OT | organotin compound |

| P | pyridyl derivative |

| PA | phenoxyacetic acid derivative |

| PY | pyrethroid |

| T | triazine derivative |

| TC | thiocarbamate |

These chemical classifications are included only for convenience, and do not represent a recommendation on the part of the World Health Organization as to the way in which the pesticides should be classified. It should, furthermore, be understood that some pesticides may fall into more than one type.

Chemical type is not shown where it is apparent from the name.

Physical state (Column 5):

Refers only to the technical compound.

| L | liquid, including solids with a melting point below 50o C. |

| Oil | oily liquid — refers to physical state only |

| S | solid, includes waxes. |

Route (Column 6):

Oral route values are used unless the dermal route values place the compound in a more hazardous class, or unless the dermal values are significantly lower than the oral values, although in the same class.

| D | dermal |

| O | oral |

LD50, mg./kg. (Column 7):

The LD50 value is a statistical estimate of the number of mg. of toxicant per kg. of body weight required to kill 50 per cent of a large population of test animals: the rat is used unless otherwise stated. A single value is given: “c” preceding the value indicates that it is a value within a wider than usual range, adopted for classification purposes: + preceding the value indicates that the kill at the stated dose was less than 50 per cent of the test animals, and is used for typographical reasons in place of the symbol >.

Table 1.

List of technical products classified in class Ia

“extremely hazardous”

| Name | Status | Main use | Chemical type |

Physical state |

Route | LD50 (mg./kg.) |

Remarks |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) |

| acrolein | C | H | L | O | 29 | ||

| aldicarb | ISO | I-S | C | S | O | 0.93 | |

| arsenous oxide | C | R | S | O | 180 | Adjusted classification; see note 1, end of table EHC 18 |

|

| brodifacoum | ISO | R | S | O | 0.3 | ||

| bromadialone | ISO | R | S | O | 1.12 | ||

| bromethalin | ISO | R | S | O | 2 | ||

| calcium cyanide | C | FM | S | O | 39 | Adjusted classification; see note 2, end of table |

|

| captafol | ISO | F | S | O | 5,000 | Adjusted classification; see note 8, end of table |

|

| chlorfenvinphos | ISO | I | OP | L | O | 10 | |

| chlormephos | ISO | I | OP | L | O | 7 | |

| chlorophacinone | ISO | R | S | O | 3.1 | ||

| chlorthiophos | ISO | I | OP | L | O | 9.1 | |

| coumaphos | ISO | AC,MT | OP | L | O | 7.1 | |

| CVP | N(J) | See chlorfenvinphos | |||||

| cycloheximide | ISO | F | S | O | 2 | ||

| DBCP | N(J) | See dibromochloropro pane | |||||

| demephion -O and -S |

ISO | I | OP | L | O | 15 | |

| demeton -O and -S |

ISO | I | OP | L | O | 1.7 | |

| dibromochloro- propane |

C | F-S | L | O | 170 | Adjusted classification; see note 3, end of table |

|

| difenacoum | ISO | R | S | O | 1.8 | ||

| difethialone | ISO | R | S | O | 0.56 | ||

| difolatan | N(J) | See captafol | |||||

| dimefox | ISO | I | OP | L | O | 1 | Volatile |

| diphacinone | ISO | R | S | O | 2.3 | ||

| disulfoton | ISO | I | OP | L | O | 2.6 | DS 68 |

| EPN | N(A,J) | I | OP | S | O | 14 | See note 7, end of table |

| ethoprop | N(A) | See ethoprophos | |||||

| ethoprophos | ISO | I-S | OP | L | D | 26 | DS 70 |

| ethylthiometon | N(J) | See disulfoton | |||||

| fenamiphos | ISO | N | OP | L | O | 15 | |

| fensulfothion | ISO | I | OP | L | O | 3.5 | DS 44 |

| flocoumafen | N(B) | R | S | O | 0.25 | ||

| fonofos | ISO | I-S | OP | L | O | c8 | |

| hexachloro- benzene |

ISO | FST | S | D | 10,000 | Adjusted classification; see note 4, end of table; DS 26 |

|

| leptophos | ISO | I | OP | S | O | 50 | Adjusted classification; see note 5, end of table; DS 38 |

| M74 | N(J) | See disulfoton | |||||

| MBCP | N(J) | See leptophos | |||||

| mephosfolan | ISO | I | OP | L | O | 9 | |

| mercuric chloride |

ISO | F-S | S | O | 1 | ||

| merkaptophos | N(U) | When mixed with merkaptophos teolovy, see demeton-O and-S |

|||||

| metaphos | ISO | See parathion-methyl |

|||||

| mevinphos | ISO | I | OP | L | D | 4 | DS 14 |

| parathion | ISO | I | OP | L | O | 13 | DS 6 |

| parathion-methyl | ISO | I | OP | L | O | 14 | DS 7; EHC 145 |

| phenylmercury acetate | ISO | FST | S | O | 24 | Adjusted classification; see note 6, end of table |

|

| phorate | ISO | I | OP | L | O | 2 | DS 75 |

| phosfolan | ISO | I | OP | L | O | 9 | |

| phosphamidon | ISO | I | OP | L | O | 7 | DS 74 |

| prothoate | ISO | AC,I | OP | L | O | 8 | |

| red squill | ISO | See scilliroside | |||||

| schradan | ISO | I | OP | L | O | 9 | |

| scilliroside | C | R | S | O | c0.5 | Induces vomiting in mammals |

|

| sodium fluoroacetate | C | R | S | O | 0.2 | DS 16 | |

| sulfotep | ISO | I | OP | L | O | 5 | |

| TEPP | ISO | AC | OP | L | O | 1.1 | |

| terbufos | ISO | I-S | OP | L | O | c2 | |

| thiofos | N(U) | See parathion | |||||

| thionazin | ISO | N | OP | L | O | 11 | |

| timet | N(U) | See phorate | |||||

| trichloronat | ISO | I-S | OP | L | O | 16 |

Notes to class Ia, Table 1

Arsenous oxide (also known as arsenic trioxide, arsenious oxide, and white arsenic) has a minimum lethal dose for humans of 2 mg./kg. Evidence of carcinogenicity for humans is sufficient.

Calcium cyanide is in Class Ia as it reacts with moisture to produce hydrogen cyanide gas. The gas is not classified under the WHO system.

Dibromochloropropane has been found to cause sterility in humans and is mutagenic and carcinogenic in animals.

Hexachlorobenzene has caused a serious outbreak of porphyria in humans. See also WHO Technical Report Series No. 555 (1974).

Leptophos has been shown to cause delayed neurotoxicity.

Phenylmercury acetate is highly toxic to mammals and very small doses have produced renal lesions: teratogenic in the rat.

EPN has been reported as causing delayed neurotoxicity in hens.

Captafol is carcinogenic in both rats and mice.

|

Appendix II. How to find out whether a certain chemical is banned, withdrawn, or severely restricted by any government

First, you will need to know the generic name of the chemical. See Appendix V (How to find the generic name(s) of a brand name chemical) in Appendices. Chemicals in the workplace.

To find out whether a specific chemical is regulated in your country, check the local laws on the handling and use of “dangerous goods”, “prohibited goods”, or “toxic substance control”. A public library, lawyer, local fire department, trade union or factory inspectorate should be able to help.

To find out whether a specific chemical is regulated in other countries, check the various United Nations publications, some of which may be available at public or university libraries or from national or international trade union organizations. The International Labour Office and the United Nations Environmental Programme have compiled listings of regulated chemicals. You may also be able to obtain a free copy of the Consolidated list of products banned, withdrawn, severely restricted or not approved by governments by writing to the United Nations Secretariat, 2 United Nations Plaza, New York, NY 10017, USA.

Appendix III. How to find a safer alternative to a dangerous chemical

You will need to know the generic name of the chemical you wish to replace. See Appendix: How to find the generic name(s) of a brand name chemical in the volume in this collection entitled Chemicals in the workplace. Appendices.

See a List of IARC evaluations. Overall evaluation of carcinogenicity to humans in the separate volume in this collection entitled Chemicals in the workplace. Appendices which classifies agents (mixtures) as to their carcinogenic risk to humans.

Identify the chemicals with similar properties by checking in Appendix: Chemical groups in the volume in this collection entitled Chemicals in the workplace. Appendices. For example, methyl ethyl ketone is listed with other ketones, such as acetone and methyl isobutyl ketone.

Compare the health and fire risks of each of the chemicals in the group to see which is less hazardous. Among the ketones, for example, acetone is considered to be safer to use than other ketones. When comparing chemicals, it is absolutely essential (1) to consider how the chemical is to be used, (2) to review several medical texts which describe the toxicity of the chemical, and (3) to consult an expert on chemical toxicology.

If any chemical is associated with causing cancer, mutations (changes in cells), or birth defects, it should be replaced immediately with a chemical which does not pose these risks. See Appendix: Chemicals which have toxic effects on reproduction and Appendix: Carcinogenic chemicals in electronics manufacturing in the volume in this collection entitled Chemicals in the workplace. Appendices.

Remember: for many chemicals, the evidence on toxicity is often not complete because of inadequate testing or failure to record all information about health effects. Thus, it is important to review every year or so the current literature on chemicals used at work. Always use the latest available edition of a textbook on toxic substances. The International Registry of Potentially Toxic Chemicals (IRPTC), a division of the United Nations Environment Programme in Geneva, Switzerland, publishes the IRPTC Bulletin twice a year providing a summary of the latest news from dozens of countries on toxicity and legislation with regard to specific chemicals.

Appendix

IV.

Basic information on first-aid stations

First-aid boxes, first-aid kits and similar containers

First-aid boxes, kits and containers must contain suitable and enough materials for delivering basic first aid, especially for bleeding, broken or crushed bones, simple burns, eye injuries and minor injuries.

In some countries, only the principal requirements are stated in regulations, for example, that adequate amounts of suitable materials and appliances must be included in first-aid kits, and that the employer must determine what precisely may be required and in which quantity, depending on the type of work, the associated risks and the configuration of the enterprise. In most countries, however, more specific requirements have been set out, with some distinction made as to the size of the enterprise and the type of work and potential risks involved.

The contents of these containers must match the skills of the first-aid personnel, the availability of a factory physician or other health personnel, and the proximity of an ambulance or emergency service. The more elaborate the tasks of the first-aid personnel, the more complete must be the contents of the containers.

A relatively simple first-aid box will usually include the following items:

First-aid boxes should always be easily accessible and should be located in a number of areas, especially where accidents could occur. The boxes should be able to be reached within no more than one to two minutes. They should be made of sturdy materials, and should protect the contents from heat, humidity, dust and abuse. They need to be clearly identified as first-aid material — in most countries they are marked with a white cross or a white crescent, as applicable, on a green background with white borders.

If the enterprise is divided into departments or shops, there should be at least one first-aid box available in each unit. However, the actual number of boxes required will be determined by the needs assessment made by the employer. In some countries the number of containers required, as well as their contents, has been established by law.

Soap, clean water and disposable drying materials should also be easily available. If possible, there should be a water tap within reach. If that is not available, water should be kept in disposable containers near the first-aid box for eye wash and irrigation.

Small first-aid kits should always be available where workers are away from the establishment in such sectors as lumbering, agricultural work or construction; where they work alone, in small groups or in isolated locations; where work involves travelling to remote areas; or where very dangerous tools or machinery are used. The contents of such kits, which should also be readily available to self-employed persons, will vary according to circumstances, but they should always include:

Specialized equipment and supplies

More first-aid equipment may be needed where there are unusual or specific risks. This applies specifically to situations where first-aid personnel are expected to assist with cases of shock, respiratory and cardiac arrest, electrocution, serious burns and, especially, chemical burns and poisonings. Equipment for resuscitation is particularly important.

This equipment and material should always be located near the site or sites of a potential accident, and in the first-aid room. Transporting the equipment from a central location such as an occupational health service facility to the site of the accident may take too long. If the equipment and supplies are located on site, they will be ready and available when the physician or nurse arrives, according to a plan which the employer must devise in advance.

If poisonings are a possibility, antidotes must be immediately available in a separate container, though it must be made clear that their application is subject to medical instruction. Long lists of antidotes exist, many for specific situations. Only an assessment of the potential risks involved will indicate which antidotes are needed.

The first-aid room

A room or a corner, prepared for administering first aid, should be available. Such facilities are required by regulations in many countries. Normally, first-aid rooms are mandatory when there are more than 500 workers at work or when there is a potentially high or specific risk at work. In other cases, some facility must be available, even though this may not be a separate room, for example, a prepared corner with at least the minimum furnishings of a full-scale first-aid room, or even a corner of an office with a seat, washing facilities and a first-aid box in the case of a small enterprise.

Whatever the specific requirements in a given enterprise, a first-aid room or other facility should meet the following requirements: