International

Labour Organization

Your

health and safety at work

Your

health and safety at work

HEALTH AND SAFETY FOR WOMEN AND CHILDREN

Goal of the Module

This Module provides trainees with basic information on some of the health and safety issues for two special categories of workers: women workers and child workers. Topics discussed include some of the reproductive health issues for women workers, such as when and how reproductive damage can occur as a result of occupational exposures, what is known about some of the occupational health hazards to child workers, what are some of the recommended actions towards eliminating child labour, and the role of the health and safety representative.

| Objectives | |

|

At the end of this Module, trainees will be able to: (1) describe several kinds of female reproductive health problems that can occur from exposure to occupational hazards; (2) state two other health and safety issues important for women workers; (3) explain why child workers are more susceptible to occupational hazards than adults; (4) state several of the health problems that have been found in child workers; (5) state two actions that could lead toward the eventual elimination of child labour; (6) state two actions that have been recommended for humanizing work for children. |

What is in this Module

Women workers face many workplace health and safety hazards. There are hazardous chemicals as well as a variety of physical and biological agents (such as radiation and bacteria) used in many workplaces which expose women workers to health and safety hazards. Additionally, there are many work situations (such as work which is highly stressful, or shift work) which may have negative effects on the health of female workers, including their reproductive health.

To date, most chemical substances and work situations have not been studied for their potential to have damaging effects on a worker's health. It is known, however, that many substances may have negative effects on the reproductive health of women workers who are exposed to them. Unfortunately, many substances are used at work anyway, despite the lack of information about possible reproductive health effects.

It is important that workers and trade unions learn as much as possible about the substances and situations in their workplaces, when information does exist. Protective measures should be implemented to ensure that pregnant workers and women who may be planning to have a child are not exposed to known or suspected reproductive health hazards.

In addition to the reproductive health issues, matters of security, rights for maternity leave, and maximum weights to be transported manually are other important health and safety issues for women workers. These are issues that should be discussed by trade unions.

The special category of child workers is also addressed in this Module. Although the subject of child workers is not one of the usual occupational health and safety issues, it is none the less an important topic because of its very sensitive nature. There are a number of health and safety issues directly related to child workers. First of all, children are not the same as adults physically and emotionally. Child workers are at a greater risk than adult workers of suffering from work-related problems. Furthermore, occupational hazards and work conditions may have permanent effects on the development of children who work.

This Module is not a manual on child labour. There are a number of other ILO publications that discuss the issue of child labour in detail. The purpose of this Module is to raise some health and safety issues related to child workers that trade unions can begin to discuss, if they are not doing so already.

|

Points to remember |

|

II. When and how does reproductive damage occur to women?

Note: The subject of reproductive health hazards in the workplace is discussed in greater detail in the Module Male and female reproductive health hazards in the workplace.

Exposure to certain hazardous substances or hazardous work conditions can affect a woman's reproductive health before or after conception takes place. Some occupational hazards can seriously affect a developing embryo or foetus (also written fetus), particularly certain chemicals and radiation. Appendix I at the back of this Module gives some examples of chemicals which are known to have negative effects on sexual behaviour and reproduction.

Adverse effects due to occupational exposure can also occur after birth, affecting the development of a baby or child. While effects that occur after birth are not considered reproductive hazards, it is important to know that newborns and children are particularly sensitive to the effects of hazardous substances.

Some workplace exposures can prevent conception. Exposure to certain substances or combinations of substances can cause changes in a woman's sex drive, damage to the eggs, changes in the genetic material carried by the eggs, or cancer or other diseases in a woman's reproductive organs.

A substance that causes changes in genetic material is called a mutagen. There are special laboratory tests, often performed on animals, which can identify substances as mutagens.

Make a list of mutagens used in your workplace. This can be done by making a list of the generic names of chemicals you use and checking them against Appendices I and II at the back of this Module. Most cancer-causing chemicals (except most solvents) are mutagens. |

|

Once fertilization occurs, some harmful substances can pass through the mother to the developing embryo or foetus. The foetus is generally thought to be at greatest risk during the first 14 to 60 days of the pregnancy, when the major organs are being formed. However, depending on the type and amount of exposure, a foetus can be harmed at any time during the pregnancy. A substance that prevents the normal development of a foetus is called a teratogen. Teratogens can pass from the blood of the mother to the blood of the foetus across the placenta.

The umbilical cord carries the blood of the foetus to the placenta where it passes close to the blood of the mother and nutrients and wastes are exchanged. It is in the placenta that teratogens can be passed on to the embryo or foetus. |

|

There are a number of chemical, biological and physical agents used in a variety of workplaces that are known to cause birth defects. Birth defects can include a wide range of physical abnormalities and behavioral or learning problems.

Other factors can also affect the health of a developing foetus, such as stress at home, smoking cigarettes, drinking alcohol or taking certain drugs and medications. These factors can combine with hazardous work situations and increase the dangers to a foetus even more.

Cigarettes, alcohol, certain drugs and medications, radiation and stress may have bad effects on a developing foetus. |

|

Occupational exposures can also harm a developing child even after it is born. It is important to know that newborns and children are particularly sensitive to chemicals or other harmful substances, such as dusts or fibres, that may be brought into the home on clothing, shoes or even skin and hair. If harmful substances are present in breast milk, then infants can also take in those substances while breast-feeding.

|

Points

to remember about when |

|

III. Other health and safety issues for women workers

There are a number of other health and safety issues which are particularly relevant for women workers. Issues of security, rights for maternity leave, and the weight of a load to be transported manually are three more important areas of concern for many women workers. While it is not within the scope of these training materials to discuss these issues in detail, it is important to raise awareness about these matters and for trade unions to begin to discuss them, if they are not doing so already. There are a number of ILO publications that discuss these points in greater detail.

It is essential that adequate measures are provided which ensure the personal safety and security of women workers. Security is of particular importance for women who work at night or in dark places such as underground areas, and for women who work alone or in isolated or remote areas of a worksite. Appendix V at the back of this Module contains ILO Convention No. 171 concerning night work, (1990) and Appendix VI Convention No. 89 concerning night work of women employed in industry (Revised), 1948, and Protocol of 1990. Find out if your country has ratified these international Conventions. Do employers comply with the terms of the Conventions if your government has accepted them?

Adequate provisions for maternity leave are also important considerations in working to protect the health and safety of women workers. Adequate maternity leave should also guarantee the worker's right to return to her job, at the same rate of pay and without loss of seniority. Appendix VII at the back of this Module contains ILO Convention No. 103 concerning maternity protection which requires that at least 12 weeks are provided as a period of maternity leave. Appendix VIII contains ILO Recommendation No. 95 concerning maternity protection.

Has your government ratified Convention No. 103? Does your country have its own national legislation providing for a minimum amount of maternity leave for women workers? If so, how much time is the minimum guaranteed leave?

In some countries, individual employers provide more maternity leave than is required by national legislation. Your union may want to begin negotiating this point with the employer. The union can also help to protect women workers by ensuring that employers comply with the guaranteed minimum maternity leave, if such policy exists in your country. If there is no national legislation in your country, your union may want to put pressure on the government to adopt legislation.

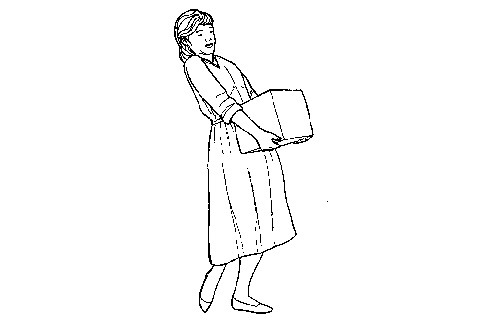

A worker's health and safety can be seriously endangered if she is required to move loads that are too heavy for her. |

|

The health and safety of women workers can be seriously endangered

if they are asked or required to move manually loads that are beyond their physical

capacity. Adequate provisions should exist to guarantee that women workers do not have to

do so. Appendix III at the back of this Module highlights the key points of ILO Convention No.

127 and Recommendation No. 128 which limit the maximum weights that employers may assign

women workers to transport manually.

Does your country have legislation which limits the maximum weight women workers may

transport manually? If not, your union may want to put pressure on the government to adopt

such protections for women workers. Are there other health and safety issues for women

workers that you can identify within your union? What are those issues?

|

Points

to remember about other |

|

|

IV. Information on the health of children at work

According to the International Labour Organization, in the early 1990s the number of children under 15 working in the world was estimated between 100 to 200 million. The majority of these child workers were and still are in developing countries. Since it is difficult, if not impossible, to know the precise number of child workers in the world, it is also generally accepted that these figures are a gross under-estimation; the actual figure may be more than double this number. One reason that the official estimates are under-estimated is that they only include full-time child workers. In addition, child labour is illegal in many countries and therefore is not reported. Even when it is reported, in many cases it is minimized for a variety of reasons.

For more recent (1995) statistics on child labour, see ILO Statistics on Working Children and Hazardous Child Labour in Brief

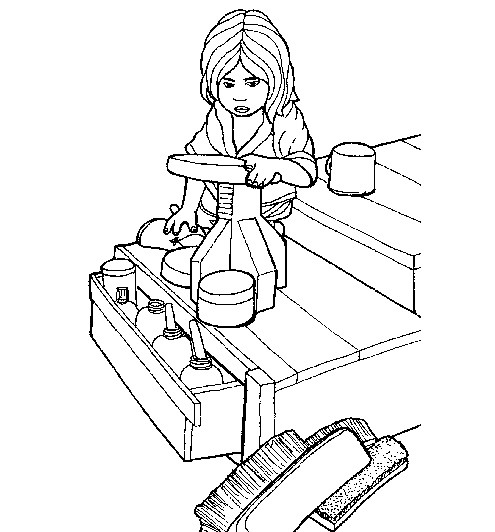

Child workers face a multitude of occupational health and safety hazards. |

|

Child labour is not a new phenomenon. What is new, however, is the systematic exploitation of children outside the family environment. There are many effects of having children in the labour market — probably the most important being the fact that working children generally do not go to school. Without schooling, a child has little opportunity to advance or have a better life. Even if a working child does manage to continue to go to school, he or she is likely to perform poorly in school, to fail and to drop out. These unfortunate results are directly related to the fact that the child works long hours at a job, is exhausted and cannot concentrate or perform in school.

The economic exploitation of working children has received a great deal of attention but the effects of work on the health of child workers have not yet been well studied. It is known that child workers face a multitude of occupational health and safety hazards, as do adults. Occupational hazards and work conditions can have permanent effects on the long-term development of children who have to work.

B. Exposure to environmental agents

In a number of occupations, child workers might be exposed to chemical and physical health hazards. Although there have been few real-life studies on the effects of occupational hazards on working children, it is assumed that children are at a higher risk than adults of suffering work-related physical health problems. In addition, emotionally, child workers are at greater risk than adult workers of suffering from work-related health problems.

Child workers can be affected more quickly and more seriously than adults exposed to the same concentrations of chemicals. Exposure limits that are recommended for adult workers are not adequate for protecting children. For some extremely toxic chemical substances such as lead, and harmful physical agents such as ionizing radiation, the only protection for children is to eliminate exposure completely.

In a number of occupations, child workers might be exposed to chemical and physical health hazards. |

|

The results of some research have shown that, at the same level of exposure, children tend to absorb higher amounts of lead than do adults. Furthermore, children are more likely than adults to develop serious permanent health effects after exposure to lead. Similar findings have been reported in studies of child workers exposed to silica in the slate-pencil industry, young girls performing spinning and weaving in a viscose fibre factory, and young workers exposed to benzene.

In addition, young workers are more likely than adults to lose their hearing from exposure to noise in the workplace. Therefore, lower exposure limits for noise are needed where children and young workers are working.

C. Working capacity and limitations

In general, the concept of work design includes: the selection and training of operators; the design of tools and machines; the design of workstations; the use of working procedures and working postures; the prescription of working hours and rest periods; the design of personal protective equipment; and the control of physical factors in the working environment.

It is very difficult to identify and eliminate risks related to work design for children since each individual child grows and develops at a different rate. With adults, it is possible to assess working capacity and limitations on a group basis. With children, however, it is necessary to make an individual assessment of each child in relation to his or her work because there is a wide range of variations within each age group.

A World Health Organization Study Group on the Special Risks of Children at Work has summarized the following results of a number of health studies of child workers:

In many developing countries, the numbers of children who suffer from under-nutrition and illness are very high. This makes it even more important to try to assess the possible risks to children that can result from problems related to work design.

It is necessary for communities and countries to examine the contribution that their children make to the economy. |

|

D. Psychosocial risks to child workers

The special situation of being both a child and a worker can create many psychosocial (meaning emotional, developmental and behavioural) risk factors for the child worker. Additionally, child workers may react differently from adults exposed to similar psychosocial risks. There are a number of common stressful psychosocial factors associated with child labour, regardless of the job. In particular, the very unfortunate socio-economic and family backgrounds that have forced the children to work in the first place are themselves a source of stress.

Most child workers do not have the opportunity to go through the normal stages of childhood development. Many of them never get the chance to develop meaningful relationships with family members, friends and other people in their community. They do not get the opportunity to play, to be spontaneous or to get an education. Most children who work are not allowed to express their feelings or needs. They are often severely disciplined and sometimes physically abused. In many countries, there is no legal protection for child workers. This means that there is no compensation available to them if they get injured at work, even if the injury leaves them permanently disabled.

Although this is a relatively new area of study, the World Health Organization has reviewed a number of studies on the social and psychosocial problems of children at work, which revealed the following results:

Workers, employers, the government, and the community in general must share the responsibility of controlling the special psychosocial risk factors that working children face. Both workers and employers need better knowledge of the basic requirements for a healthy work environment, of the ways to adapt work to the capacity and needs of each worker and information on ways to maintain a healthy and safe working environment. The community and the government can intervene with socio-economic planning, and determine the types of work appropriate for children, taking their health and education into consideration.

E. Primary health care for child workers

In general, working children do not receive health care. General health services are not organized to provide health care to working children, and occupational health services are organized to look after the health of adult workers and young people (15 years and over). In fact, one of the tasks of occupational health services is to exclude children who are too young to work. The reality is that young children who must work will work — but without the protection of any health services. Primary health care may be the only way to provide health care to working children.

One of the goals of primary health care is to "reach people where they live and work", and this includes child workers. Primary health care services, utilizing community health workers and any facilities a workers' health service can make available, should be able to provide the basic services that are needed to protect child workers.

It is essential that child workers receive primary health care. |

|

Community health workers, an essential component of primary health care, can reach children at work, regardless of the type of employment — unlike labour inspectors. Health workers can collect information on all children in any workplace. This information can be used to create community awareness of the problem of child labour and can help the community to take actions to control the problem.

|

Points

to remember |

|

|