International

Labour Organization

Your health and safety at work

AIDS AND THE WORKPLACE

There are many ways that HIV is not transmitted

AIDS and everyday life

|

This does not transmit AIDS

HIV cannot be transmitted through casual contact. Personal contact in the workplace is casual. You cannot get HIV by any of the following activities:

Research shows that family members of people with HIV/AIDS have not been infected with the virus through normal household contact. Even people who have bathed or slept in the same bed with AIDS patients have not become infected.

In the absence of any effective treatment, prevention is the only way to combat the spread of AIDS, since certain sexual and drug-related practices greatly increase the risk of contracting the disease. Only a change in this behaviour can protect us and limit the spread of the disease until treatment and a vaccine are available. Your state of health in relation to AIDS depends to a large degree on you . . . |

|

AIDS |

What is safer sex?

The safest sex is no sex, or sex with only one partner who is not infected. Take precautions if you are sexually active with more than one partner, or if you are unsure about whether your sexual partner is infected or not. Use latex condoms (also called preservatives or rubbers) for all penetrative sexual acts (anal, vaginal, oral). Using a spermicide may also help to reduce the risk of sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV, but spermicides are not an alternative to condoms.

Exposure to blood

Always avoid exposure to large quantities of blood. Intact skin (no cuts, tears, breaks, dermatitis, etc.) is a good barrier against the AIDS virus. However, it is not always possible to know if you have minor cuts or scratches. Cover known wounds with dressings. Treat all blood as potentially infected: this avoids discrimination and protects against other bloodborne diseases, e.g. hepatitis. Therefore the best rule is to avoid skin contact with blood, and to wear gloves if you come into contact with blood. Remember: the virus has to get inside the bloodstream in a relatively high concentration for a person to get infected.

Cleaning up blood spills

Spilt blood should be soaked up with absorbent material (cloth, rags, paper towels or sawdust), direct skin contact with the blood being avoided. Blood spills can be cleaned up using detergent-disinfectant formulations — chemical germicides. In addition to these, a solution of household bleach and water (prepared daily) is an inexpensive and effective germicide and will kill the HIV virus when used properly. Remember to wear disposable gloves when cleaning up blood spills using chemical germicides or bleach and use them in well ventilated areas. See Appendix II.

How can the AIDS virus be inactivated?

Fortunately, the AIDS virus is not very resistant outside of the body. For this reason, it is relatively easy to inactivate in the ambient environment.

If you think you may come into contact with blood, you are urged to take certain recommended precautions. This is especially important for people who may have cuts, abrasions or lesions (from dermatitis, for example) who perform first aid or clean-up functions that may expose them to blood or body fluids containing visible blood. Appendix II at the back of this Module contains the World Health Organization Guidelines on AIDS and first aid in the workplace. You can get other information on AIDS from:

Global Programme on AIDS,

PPC

World Health Organization

20, avenue Appia

1211 Geneva 27

Switzerland

Can saliva, sweat, tears or urine spread HIV?

Although small amounts of the virus have been found in the saliva, sweat, tears and urine of some AIDS patients, the concentrations were extremely low. These body fluids are not considered likely to transmit HIV because the quantity found is generally below the level necessary to cause infection. However, if these body fluids contain visible blood, then the recommended precautions referred to above should be used.

Can HIV be spread through food?

Scientists have never found a single documented case of AIDS which was transmitted through food. Cooking food would kill the virus anyway.

Can mosquitos spread HIV?

There have been no recorded cases of anyone becoming infected from mosquito bites (or bites from any other insects).

Is there a risk of becoming infected with HIV when providing first aid?

First aid treatment which involves contact with blood presents a very small risk of transmission of HIV (and other bloodborne infections such as hepatitis B) from an infected person. In fact, there are no reported cases of HIV transmission from mouth-to-mouth resuscitation with an infected person. However, as a precaution, when providing first aid, you can reduce the possibility of infection by following these rules:

Is there a test for AIDS?

There is a test for the HIV antibody — which is a test for HIV infection, not for AIDS. When the virus enters the body, “antibodies” are produced by the body's immune system. There are tests to find these antibodies in the blood. A positive test means that antibodies have been found and that the person has been infected with the virus, can transmit the virus to others, and is likely to develop AIDS. A negative test means that no antibodies have been found and the person is not infected. However, there is a “window period” between the time of exposure to the virus and the time antibodies appear (up to three months) when the test will show a negative result even though the person is actually infected (a false-negative result). This means that a test may not be able to find antibodies for up to three months after the person has been exposed to the virus.

Who should get tested?

If you are worried that you have been exposed to HIV, you may want to consider being tested. You should always seek counselling before deciding whether or not to be tested. Counselling will give you information about the testing procedure and help you to understand the implications of the test result, whether it is negative or positive.

|

|

|

|

The World Health Organization (WHO), in cooperation with the International Labour Office (ILO), held a meeting in Geneva, Switzerland in June 1988 on AIDS and the workplace. Experts from governments, trade unions and employers as well as from the public health, medical, legal and health education sectors agreed unanimously that two fundamental principles should guide policies toward workers with HIV infection (and AIDS):

Most workers have no risk of becoming infected with HIV in the workplace because HIV is not spread by casual contact. However, any worker who may come into contact with blood, semen, vaginal fluids or body fluids containing blood may risk exposure to HIV.

A. Jobs with an increased risk of exposure

Medical and paramedical personnel and AIDS

Health professionals are in daily contact with patients, their body fluids and their blood. Some of these patients or these fluids may be contaminated with the HIV virus.

Several studies have estimated the risk of HIV infection in the work environment. Several thousand health workers in direct contact with infected patients were followed over a period of several months without the use of any particular precautions. Among those who had an accidental exposure, the risk of infection was estimated to be between 0 and 0.76 per cent.

|

|

To date, a total of twenty health workers, throughout the world, may possibly have acquired HIV infection at work. Seroconversion, i.e. passage from seronegativity to seropositivity, has been documented in the majority of these subjects. Most cases of infection appear to be secondary to injury with a contaminated needle or cut. Other people have been infected by contact with blood or blood fluid onto damaged skin or mucous membranes.

|

|

|

With the hygiene precautions usually recommended in the hospital environment, the risk of HIV transmission to health personnel is even lower. The French Ministry of Health has proposed certain recommendations for measures to be taken to prevent transmission, in the work environment, of HIV and an other micro-organisms transmissible by blood, sexual secretions and certain biological fluids.

These precautions are described as being universal, as they must be applied every day in all patients, as it is impossible to identify all seropositive subjects. Furthermore, several other microorganisms, such as hepatitis B virus, cytomegalovirus and other retroviruses (HIV 2, HTLV) are also transmitted by blood.

Workers who may be at an increased risk because of their work include:

|

|

There have been a few cases of health care workers who have been infected with HIV from exposure to contaminated blood by accidentally being stuck with needles (“needlesticks”), exposure of mucous membranes to blood (through the mouth, eyes or nose) or blood spills on broken skin. Generally, contact with saliva, urine, sweat or tears is not considered a normal exposure route to HIV unless these substances contain blood that you can see. Other workers such as ground-keepers and custodians may be exposed to HIV from glass or needles which have been thrown away and are contaminated by infected blood.

Hepatitis B

If workers are exposed to

blood, they also risk exposure to another dangerous virus transmitted in blood

(bloodborne) — the hepatitis B virus (HBV). Hepatitis B is a serious — and

potentially deadly — disease of the liver. Hepatitis B is much easier to transmit

than HIV because HBV is 100,000 times more concentrated in the blood than HIV. Fortunately

a safe vaccine exists for hepatitis B. However, it may not be available in all countries.

Ideally, employers should make the vaccine available at no cost to workers with potential

exposure.

B. Preventing workplace exposure

Because it is impossible to know who is infected with the HIV or HBV, it is recommended that all blood be treated as if it were infected — this means that all blood should be treated as if it were a toxic substance. Workers exposed to blood should follow the guidelines recommended by the World Health Organization. Appendix II, World Health Organization Guidelines on AIDS and first aid in the workplace at the back of this Module contains more detailed information on preventing the transmission of HIV in work that may involve exposure to infected blood or infected persons.

What if a worker is exposed at work?

A written policy stating what to do and whom to contact in case of exposure should be developed in all workplaces where workers may be exposed to blood or other body fluids. Workers should be familiar with the policy, and it should be posted where everyone can see it. If a worker is exposed to blood or other potentially infectious fluids:

Note: All procedures must protect the confidentiality of the exposed worker. If workers suspect that the process is not completely confidential, they may be reluctant to report the injury, or to seek needed treatment and counselling.

Engineering controls

Engineering controls should be the first choice to control hazards in the workplace. Engineering controls remove the hazard, rather than require the worker to use special protective equipment or follow special work procedures. Engineering controls are available to protect workers against needlesticks. For example, some unions are asking health care employers to get new devices like “self-sheathing needles” that allow the needle to remain covered before, during and after it is used. They are also pressing for other types of safer procedures and equipment which have become available. Proper worker training in good housekeeping practices is also vital for the prevention of needlesticks.

Infection control plans

Experts and some regulatory agencies recommend that every employer prepare an infection control plan designed to reduce or eliminate exposure if the workers face possible occupational exposure to HIV and HBV. The infection control plan should have specific procedures for specific categories of workers and job tasks and, most important, it should be supported and followed by all supervisors.

Is there ever a reason to know if someone is infected with HIV?

In situations where there is a real risk of exposure, such as in a hospital, the best solution is to assume that anyone could be infected and take the same precautions for everyone. Since it is impossible to know everyone who is infected, workers must be especially careful when handling all blood and certain body fluids.

|

|

|

|

V. AIDS education in the workplace

AIDS education training seminar |

|

The workplace is an important environment for promoting the health of all workers as well as for disseminating information and education about the transmission and prevention of HIV/AIDS. Education in the workplace is particularly important since many people express fear about having contact with people who have HIV infection and AIDS. At work, these fears can affect workers' attitudes towards co-workers with AIDS or even towards workers suspected of being in “high-risk groups”.

Co-workers may have serious concerns when they learn that a worker has AIDS or is infected with HIV. They may ask for absolute proof that AIDS cannot be transmitted casually. Fears about contamination may surface. Workers may think about requesting transfers, or not using the same telephones, drinking fountains or workplace equipment. Some workers may be convinced that they are at risk just by being near an infected co-worker. Unions must take action to fight prejudice or discrimination.

The best solution to these problems is a worker education programme to decrease fears and to make sure everyone has accurate information about AIDS. To be most effective, workplace educational programmes on HIV/AIDS should be developed cooperatively between management, workers and their representatives and the occupational health service, if there is one.

Unfortunately, workers with HIV or AIDS often face discrimination in the workplace. This can include loss of job, violations of confidentiality, unnecessary restrictions placed on infected workers, and being passed over for promotions, better work assignments, and other rights.

There are several tools that unions can use to fight discrimination, including:

|

|

|

|

VI. AIDS and the workplace policy issues

In many workplaces, labour and management have worked together to develop a joint policy on HIV/AIDS and other chronic illnesses. If such a policy is developed, it should be circulated widely and all management and workers should understand it. The policy could be incorporated into existing contract language.

When developing HIV/AIDS-related policy and educational programmes for the workplace, employers and trade unions should utilize the expertise of any relevant non-governmental and community-based organizations. This type of collaboration can save time and effort by helping to share knowledge and procedures that are known to be effective.

Policy development and implementation is a dynamic process. Therefore, HIV/AIDS workplace policies should be:

The following are some recommended points for workplace policy for HIV/AIDS.

|

Points to remember about AIDS and the workplace policy issues |

|

|

VII. Role of the health and safety representative

Health and safety representative |

|

As a health and safety representative, your co-workers will bring many problems to you. It may happen that a union member will confidentially tell you that he or she is infected with HIV and needs your help. There will be many issues for you to deal with in such a situation:

The worker will probably want to keep working. You may need to work together with the union to make sure that the worker continues to work as long as he or she is physically able.

You may have to confront possible discrimination against the infected worker, as well as the fears of management and co-workers.

You may need to get information for the worker regarding medical treatment, possible special employment options, benefits, insurance, etc.

You may have to confront issues of confidentiality.

It is not easy to be a health and safety representative under the best of circumstances. Helping members who have life-threatening diseases can be stressful. Dealing with other members who are afraid, uninformed, or even prejudiced can also create stress. It is also important to recognize your own fears and prejudices. If you feel uncomfortable or overwhelmed dealing with the issue of AIDS, try to find support from others in the union, or from members working on the health and safety or grievance committees, for example.

Remember that the World Health Organization's Global AIDS Programme can lend assistance to you, including providing you with AIDS information pamphlets - available in a number of different languages - which you can distribute in your workplace and union. The local and regional offices of the World Health Organization and the International Labour Office are other resources for assistance.

|

AIDS is a problem all over the world today and increasingly it is an issue which trade unions must confront, as well as individuals, governments, etc. There are three ways that HIV is known to be transmitted: by sexual intercourse with an infected person where there is an exchange of body fluids, by blood-to-blood contact, and from an infected mother to her unborn child. HIV is not spread by casual contact and therefore most workers have no risk of becoming infected with HIV at work. Exposure to HIV/AIDS can be prevented in those particular occupations where there is a potential risk of exposure. In these occupations, it is important that workers are provided with education in the methods of prevention. Even where there is no occupational risk of exposure, workers should still receive education on the facts known about HIV/AIDS in order to decrease the potential for fear and prejudice. HIV and AIDS have given rise to a number of important policy issues which trade unions must begin to address with their members. |

Exercise.

HIV in the workplace: Case-study and role play

|

Note to the instructor For this exercise, ask the class participants if anyone has already experienced a workplace issue involving HIV/AIDS. If someone in the class has an example, it is recommended that you use that case in this exercise since it may have more personal value to the class members. Instructions Ask trainees to work in small groups of three to five people for this exercise. Give each group a copy of the case-study and ask them to read and discuss it. (If you cannot make copies, you can read it out loud to the class). One person in each group should take notes for the group, writing down the group's suggestions for handling the issues, and any other issues that the case raises for them. Approximately 20 minutes are recommended for this part of the exercise. Follow the small group discussion with a labour/management role play of confronting the issues and attempting to resolve the situation. Ask for volunteers for the various roles. The roles include: a union representative, a management representative, a health and safety committee representative, a worker with AIDS, a line supervisor, two co-workers afraid to work with the infected worker, and any other roles you would like to include. The rest of the class should observe and be prepared to discuss how the issues were handled. Approximately 20 to 30 minutes are recommended for the role play. Leave at least 15 to 20 minutes at the end of the exercise for a class discussion. |

A health and safety representative in a factory learns that a co-worker is HIV positive. The worker has been open about his condition; everyone in the factory knows he is HIV positive.

The health and safety representative has heard co-workers discussing their fears of working with him. They don't want to share the same equipment or eating area with him. There have been rumours that people are requesting job transfers. There have been comments made by management too; the line supervisor is not so sure that it is safe to work with this worker.

The situation has reached a crisis. The health and safety representative is afraid there will be trouble unless immediate action is taken.

How should the various people involved handle this situation?

|

|

Consider the following issues. What did your group decide on each of these issues? Are any of these good strategies for action?

|

|

Acute disease: a disease of short duration that often has sudden severe symptoms.

AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome): a disease caused by infection with HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) that damages the body's immune system.

Antibodies: substances (proteins) that are produced by the body's immune system as part of its response in fighting infections.

Chronic disease: a disease lasting a long time, or recurring often.

Condom: also known as a preservative or “rubber”. A sheath (usually made of latex) used to cover the penis during sexual intercourse to prevent semen from entering a woman to prevent pregnancy and to reduce the risk of sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV/AIDS in both men and women.

Engineering controls: protective measures that are taken to prevent exposure to a toxic substance by changing the equipment or instruments that are used to do the job.

Exposure: coming into contact with an infectious agent (such as bacteria, fungi, viruses, etc.) or toxic substance (chemicals, etc.).

HBV: hepatitis B virus

Healthy carriers: people who have micro-organisms in their body (such as bacteria, viruses, etc.) but do not show any signs of disease and are healthy. However, they may transmit the micro-organism to other people. In the case of HIV/AIDS, this term is inappropriate to describe persons who have the virus but who are in apparently good health, since some (or perhaps all) of these people will later develop the disease and therefore cannot be considered to be perfectly healthy. It is more accurate to use the term “asymptomatic carrier” (literally meaning “without symptoms”) for these people. This means that they carry the micro-organism - which they can transmit to others - but do not show any signs of the disease.

Hepatitis B: a viral infection that damages the liver. Effects can range from inflammation to cirrhosis of the liver, and death.

High-risk groups: refers to individuals at greatest risk of developing a particular disease. In the case of HIV/AIDS, the high-risk groups are male homosexuals with multiple partners, injecting drug users, haemophiliacs, prostitutes, sexual partners of any of these groups, and children born to seropositive mothers. (See also seropositive.)

HIV (human immunodeficiency virus): the name of the virus that causes AIDS.

HIV-positive: a person who has been tested and is found to be infected with HIV.

Homosexuality: sexual attraction for individuals of the same sex. Homosexuality may be occasional or exclusive.

Immune system: the system in the body that attempts to destroy substances (viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites) that are not part of the body and which can cause disease.

Infection: an invasion of the body (entry) by a disease-causing organism.

Latent infection: infection from microbes which does not have any clinical signs in the patient. The patient is referred to as a “healthy carrier”. However, in the case of HIV infection, it is preferable to use the term “asymptomatic carrier”. (See also healthy carriers.)

Pandemic: (disease) prevalent over the whole of a country or over the whole world.

Preservative: see condom.

Semen: fluid produced by the seminal vesicles and the prostate gland in men which contains the sperm. In infected males, semen also contains cells infected with HIV and is therefore able to transmit the infection to sexual partners.

Seroconversion: the appearance of antibodies in the serum (the liquid part of the blood) so that a person who was previously antibody-negative becomes antibody-positive. With HIV, seroconversion (the appearance of antibodies to HIV) usually occurs 4 to 12 weeks after a person becomes infected.

Serological test for HIV: blood test that allows the presence of antibodies to HIV in the body to be detected.

Seropositive: in the case of HIV/AIDS, a person with a positive screening test for antibodies directed against HIV. This person has been in contact with the virus and should be considered as capable of transmitting the virus to others. When the test does not detect antibodies, the person is said to be “seronegative”.

STD: abbreviation for sexually transmitted disease. STDs are diseases that can be contracted by means of sexual relations. AIDS is essentially a sexually transmitted disease.

Symptomatic HIV infection: this condition has commonly been referred to as AIDS-related complex (ARC). Signs and symptoms that HIV-infected persons may exhibit during the symptomatic stage of infection include generalized lymphadenopathy (swollen lymph glands), oral lesions and non-specific health complaints such as persistent diarrhoea. The symptoms are not as severe as those that define AIDS. (It is more accurate to describe a patient's condition with a description of symptoms, which may cover a wide range of conditions, and laboratory evidence of HIV infection rather than using the term “ARC”.)

Virus: one kind of micro-organism that causes disease.

Appendix

I.

Policy principles and components:

Statement from the Consultation on AIDS and the workplace, Geneva, 27-29 June 1988,

World Health Organization in association with International Labour Office.

Global Programme on AIDS.

The Consultation dealt with occupations and occupational settings in which the work does not involve a risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV between workers, from worker to client, or from client to worker; it did not consider occupational situations such as those of health workers, in which a recognized risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV may occur.

III. Policy principles

Protection of the human rights and dignity of HIV-infected persons, including persons with AIDS, is essential to the prevention and control of HIV/AIDS. Workers with HIV infection who are healthy should be treated the same as any other worker. Workers with HIV-related illness, including AIDS, should be treated the same as any other worker with an illness.

Most people with HIV/AIDS want to continue working, which enhances their physical and mental well-being and they should be entitled to do so. They should be enabled to contribute their creativity and productivity in a supportive occupational setting.

The World Health Assembly resolution (WHA41.24) entitled, “Avoidance of discrimination in relation to HIV-infected people and people with AIDS” urges Member States:

“...(1) to foster a spirit of understanding and compassion for HIV-infected people and people with AIDS ...;

(2) to protect the human rights and dignity of HIV-infected people and people with AIDS ... and to avoid discriminatory action against, and stigmatization of them in the provision of services, employment and travel;

(3) to ensure the confidentiality of HIV testing and to promote the availability of confidential counselling and other support services ...”

The approach taken to HIV/AIDS and the workplace must take into account the existing social and legal context, as well as national health policies and the Global AIDS Strategy.

IV. Policy development and implementation

Consistent policies and procedures should be developed at national and enterprise levels through consultations between workers, employers and their organizations, and where appropriate, governmental agencies and other organizations. It is recommended that such policies be developed and implemented before HIV-related questions arise in the workplace.

Policy development and implementation is a dynamic process, not a static event. Therefore, HIV/AIDS workplace policies should be:

(a) communicated to all concerned;

(b) continually reviewed in the light of epidemiological and other scientific information;

(c) monitored for their successful implementation;

(d) evaluated for their effectiveness.

V. Policy components

Persons applying for employment: Pre-employment HIV/AIDS screening as part of the assessment of fitness to work is unnecessary and should not be required. Screening of this kind refers to direct methods (HIV testing) or indirect methods (assessment of risk behaviours) or to questions about HIV tests already taken. Pre-employment HIV/AIDS screening for insurance or other purposes raises serious concerns about discrimination and merits close and further scrutiny.

Persons in employment:

HIV/AIDS screening: HIV/AIDS screening, whether direct (HIV testing), indirect (assessment of risk behaviours) or asking questions about tests already taken, should not be required.

Confidentiality: Confidentiality regarding all medical information, including HIV/AIDS status, must be maintained.

Informing the employer: There should be no obligation on the employee to inform the employer regarding his or her HIV/AIDS status.

Protection of employee: Persons in the workplace affected by, or perceived to be affected by HIV/AIDS, must be protected from stigmatization and discrimination by co-workers, unions, employers or clients. Information and education are essential to maintain the climate of mutual understanding necessary to ensure this protection.

Access to services for employees: Employees and their families should have access to information and educational programmes on HIV/AIDS, as well as to relevant counselling and appropriate referral.

Benefits: HIV-infected employees should not be discriminated against including access to and receipt of benefits from statutory social security programmes and occupationally related schemes.

Reasonable changes in working arrangements: HIV infection by itself is not associated with any limitation in fitness to work. If fitness to work is impaired by HIV-related illness, reasonable alternative working arrangements should be made.

Continuation of employment relationship: HIV infection is not a cause for termination of employment. As with many other illnesses, persons with HIV-related illnesses should be able to work as long as medically fit for available, appropriate work.

First aid: In any situation requiring first aid in the workplace, precautions need to be taken to reduce the risk of transmitting bloodborne infections, including hepatitis B. These standard precautions will be equally effective against HIV transmission.

Appendix

II.

World Health Organization Guidelines on AIDS and first aid in the workplace

HIV transmission

HIV has been isolated from many body fluids of infected persons. However, only blood, semen, vaginal and cervical fluids, and breast milk have been implicated in transmission of the virus. Epidemiological studies throughout the world have shown that there are three modes of transmission of HIV:

There is considerable evidence that HIV cannot be transmitted by the respiratory or gastrointestinal routes or by casual person-to-person contact in any setting (such as school, household, social, work, or prison). Nor is HIV transmitted via insects, food, water, toilets, swimming-pools, sweat, tears, shared eating and drinking utensils, or other agents such as clothing or telephones.

HIV has not been shown to be transmitted in the workplace except in health care or research laboratory settings. The few reported cases of HIV transmission to health care workers have resulted from exposure to the blood of an HIV-infected patient as a result of needlestick injury, blood on broken skin, or splashing of blood into the eyes or mouth (mucous membranes). Although accidents such as these occur with some frequency in health care settings, they have only rarely led to HIV infection of health care workers.

In addition to HIV, other serious infections, such as hepatitis B and non-A non-B hepatitis can be transmitted by blood.

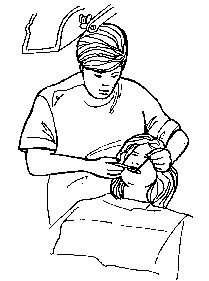

HIV transmission and the first aider

In relation to HIV transmission, the major concerns in first aid are mouth-to-mouth resuscitation and the management of bleeding, two situations where contact with the body fluids of another person may occur.

Mouth-to-mouth resuscitation

A worker who is unconscious and no longer breathing spontaneously (for example because of a heart attack, an electric shock, or a blow to the head) may require mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. Resuscitation must be started immediately. Mouth-to-mouth resuscitation is a life-saving procedure and should not be withheld through fear of contracting HIV or other infection.

HIV transmission from mouth-to-mouth resuscitation has not been reported. Although HIV has been found in saliva, it is present in extremely small quantities and no cases have been reported in which transmission has been shown to have occurred through saliva.

Although it has never been substantiated, there is a theoretical risk that HIV could be transmitted if the person in need of resuscitation is bleeding from the mouth. First aiders should use a clean cloth or handkerchief, when available, to wipe away any blood from the person's mouth.

Mouth-pieces, resuscitation bags, or other ventilation devices should only be used by people specially trained to use them. They are not recommended for use by general first aiders as incorrect use may lead to further injury and bleeding. The absence of such equipment should not be used as a reason to withhold mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

Bleeding

Workers who are bleeding require immediate attention. The first aider must not hesitate to help them as some wounds may be life-threatening (e.g. a spurting artery).

Whenever feasible, the first aider should instruct the person bleeding to apply pressure to the wound himself or herself, using a clean thick cloth. If he or she is unconscious or uncooperative, or if the wound is too large or is located in a place the person cannot reach, the first aider should apply pressure to the wound with a clean cloth or another barrier, avoiding direct contact with blood. Gloves should be used if available; if not available, another barrier such as a cloth or clothes should be used to prevent skin contact with blood. However, since bleeding may be life-threatening, the absence of gloves should not be used as a reason to withhold first aid.

Special care should be taken to prevent blood from coming into contact with broken skin or the mucous membranes of the first aider. If the first aider's hand are contaminated with blood, he or she should take care not to touch his or her own eyes or mouth.

Hands should always be washed with soap and water as soon as possible after administering first aid.

Cleaning up blood spills

Spilt blood should be soaked up with absorbent material such as a cloth, rag, paper towel or sawdust, direct skin contact with the blood being avoided. The blood-soaked absorbent material should then be disposed of in a plastic bag, burnt in an incinerator, or buried. The area contaminated with the blood should then be washed with a disinfectant (preferably sodium hypochlorite (household bleach) diluted 1:10 with water, to give 0.1-0.5 per cent available chlorine) to clean up remaining blood. Rubber household gloves should be worn if available when spilt blood is being cleaned up. If gloves are not available, another barrier such as a large wad of paper towels should be used to avoid direct skin contact with the blood. Hands should always be washed with soap and water after cleaning up blood or other body fluids.

Clothes or cloths that are visibly contaminated with blood should be handled as little as possible. Rubber household gloves should be worn if available, and the clothes or cloths should be placed in and transported in leakproof bags. They should be washed with detergent and hot water (at least 70oC (160oF) for 25 minutes; or if in cooler water (less than 70oC (160oF)), with a detergent suitable for cold water washing.

Additional measures

First aiders should be careful with broken glass and other sharp objects that may be in the accident area. They should also ensure that any open cuts or wounds they have are covered to prevent exposure to blood while they are providing first aid.

Workers who have been exposed to blood

If the guidelines give here are adhered to, the risk of acquiring bloodborne infection, including HIV, will be significantly reduced. Even so, it is not possible to guarantee that exposure will not occur. Workplaces should therefore develop policies to meet those situations where first aiders are injured or are exposed to blood while administering first aid.

If first aiders are exposed to blood on skin that is not intact, they should wash the affected area with soap and water as soon as possible. Exposed mucous membranes should be washed with water.

A first aider who is injured by a sharp object that is contaminated with blood (e.g. a used needle) should encourage bleeding, wash the wound thoroughly with soap and water and, if appropriate, apply a dressing. To determine whether further action is needed, the injury should be assessed for the type and severity of the wound - puncture, surface or deep laceration, contamination of non-intact skin or mucous membrane - and for the extent to which the wound may be contaminated with blood.

Obviously, the more severe the wound the greater the concern should be, not only for HIV infection but for all bloodborne infections. The decision whether additional evaluation is necessary should be made by the first aider jointly with the health care provider concerned.

In rare instances, a first aider may sustain injuries of sufficient severity to warrant further investigation, including assay of the first aider's blood for HIV and other infections such as hepatitis B.

If a first aider requests HIV antibody testing, this should be performed as soon as possible after the exposure. If the initial test is negative, follow-up testing should be performed three and six months later. In the interim, counselling should be available to the first aider and should deal with the low risk of acquiring infection as well as the first aider's concerns. He or she should be counselled on the need to prevent possible transmission of HIV during this period through, inter alia, sexual intercourse, the use of intravenous drugs, and pregnancy. If a worker becomes HIV antibody positive at any point, continuing counselling should be provided. If the test immediately after the exposure is positive, it cannot be a result of the exposure: the person must have been infected with HIV previously. He or she should be referred for counselling, which should include advice on how to prevent transmission of HIV.

Training in first aid

First aid training provides an opportunity to disseminate accurate information on HIV infection and AIDS to members of the community. People who receive training in first aid will subsequently be able further to disseminate accurate information within the community.

First aid training in the workplace should include clear instruction on the ways in which HIV is and is not transmitted. This is especially important, since the myths surrounding this topic may interfere with potentially life-saving first aid measures.

First aid training should emphasize that, even after parenteral exposure to HIV-infected blood, the risk of acquiring infection is extremely low, about one in 250 exposures. First aiders should be taught the precautions needed to avoid contact with blood or body fluids, since such precautions significantly reduce the risk of bloodborne infection.

First aid is generally given to alleviate suffering and in a spirit of compassion. This should be stressed. The first aider should be urged to weigh the extremely small and so far theoretical risk of acquiring HIV infection in providing first aid against the benefit gained by the person receiving first aid.

A number of organizations in many countries train large numbers of first aiders both within and outside the workplace. Employers should be encouraged to utilize the expertise of those organizations in planning first aid training courses or first aid interventions within the workplace.