Finance & Development

ROSS LEVINE

Introduction

Impact on development

Stock markets versus banks

Tips for policymakers

OVER THE past 10 years, the total value of stocks listed in all of the world's stock markets rose from $4.7 trillion to $15.2 trillion, while the share of total world capitalization represented by the emerging markets jumped from less than 4 percent to almost 13 percent. Trading in the emerging markets also surged: the value of shares traded climbed from less than 3 percent of the world total in 1985 to 17 percent in 1995.

The emerging markets have attracted the interest of international investors while raising a number of critical questions for policymakers in developing countries: Do stock markets affect overall economic development and, if so, how? What is the relationship between stock markets and banks in fostering economic growth? And, how can developing countries benefit from stock market growth?

Do stock markets affect overall economic development? Although some analysts view stock markets in developing countries as "casinos" that have little positive impact on economic growth, recent evidence suggests that stock markets can give a big boost to economic development.

Stock markets may affect economic activity through the creation of liquidity. Many profitable investments require a long-term commitment of capital, but investors are often reluctant to relinquish control of their savings for long periods. Liquid equity markets make investment less risky--and more attractive--because they allow savers to acquire an asset--equity--and to sell it quickly and cheaply if they need access to their savings or want to alter their portfolios. At the same time, companies enjoy permanent access to capital raised through equity issues. By facilitating longer-term, more profitable investments, liquid markets improve the allocation of capital and enhance prospects for long-term economic growth. Further, by making investment less risky and more profitable, stock market liquidity can also lead to more investment. Put succinctly, investors will come if they can leave.

There are alternative views about the effect of liquidity on long-term economic growth, however. Some analysts argue that very liquid markets encourage investor myopia. Because they make it easy for dissatisfied investors to sell quickly, liquid markets may weaken investors' commitment and reduce investors' incentives to exert corporate control by overseeing managers and monitoring firm performance and potential. According to this view, enhanced stock market liquidity may actually hurt economic growth.

The empirical evidence, however, strongly supports the belief that greater stock market liquidity boosts--or at least precedes--economic growth. To see how, consider three measures of market liquidity--three indicators of how easy it is to buy and sell equities.

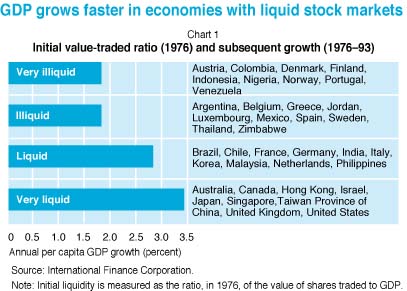

One commonly used measure is the total value of shares traded on a country's stock exchanges as a share of GDP. This ratio does not directly measure the costs of buying and selling securities at posted prices. Yet, averaged over a long time, the value of equity transactions as a share of national output is likely to vary with the ease of trading. In other words, if it is very costly or risky to trade, there will not be much trading. This ratio is used to rank 38 countries by the liquidity of their stock markets in four different groups. The nine countries with the most illiquid markets are in the first group; the nine countries with the most liquid markets--that is, with the largest value-traded-to-GDP ratios--are in the fourth group; the second and third groups, each of which contains 10 countries, fall between the two extremes of liquidity. Countries that had relatively liquid stock markets in 1976 tended to grow much faster over the next 18 years than countries with illiquid markets.

| Our study, which is based on a total of 38 countries, includes both industrial and developing countries. This is because some developing coutnries have more liquid stock exchanges than countries with higher per capita GDP. |

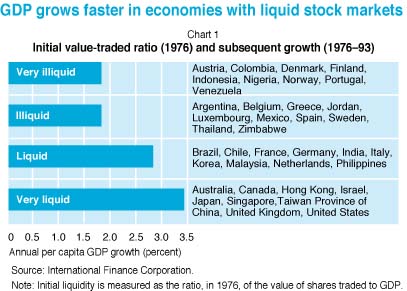

The second measure of liquidity is the value of traded shares as a percentage of total market capitalization (the value of stocks listed on the exchange). This turnover ratio measures trading relative to the size of the stock market. Chart 2 indicates that greater turnover predicted faster growth. The more liquid their markets in 1976, the faster countries grew between 1976 and 1993.

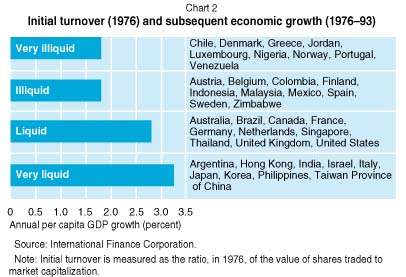

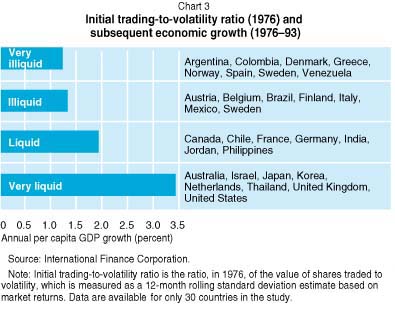

The third measure is the value-traded-ratio divided by stock price volatility. Markets that are liquid should be able to handle heavy trading without large price swings. As Chart 3 shows, countries whose stock markets were more liquid in 1976--countries with higher trading-to-volatility ratios--grew faster over the next 18 years than countries with less liquid markets. As demonstrated in the series of papers on which this article is based (see background note), the strong link between stock market liquidity and economic growth continues to hold when controlling for other economic, social, political, and policy factors that may affect economic growth, and when using instrumental variable estimation procedures, various periods, and different country samples. The basic conclusion that emerges from this statistical work is that stock market development explains future economic growth.

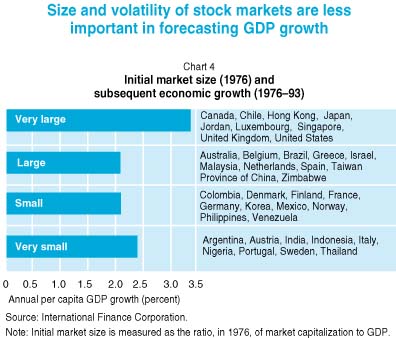

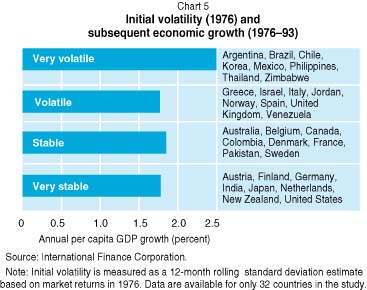

What is important is that other measures of stock market development do not tell the same story. For example, stock market size--as measured by dividing market capitalization by GDP--is not a good predictor of economic growth (Chart 4), while greater stock price volatility does not necessarily predict poor economic performance (Chart 5). Empirically, it is not the size or volatility of the stock market that matters for growth but the ease with which shares can be traded.

Countries may be able to garner big growth dividends by enhancing the liquidity of their stock markets. For example, regression analyses suggest that if Mexico's value-traded-to-GDP ratio in 1976 had been the same as the average for all 38 countries in our sample (0.06 instead of Mexico's actual ratio of 0.01), the annual income of the average Mexican would be 8 percent higher today. This type of forecast does not explain how to enhance liquidity, but it does give an indication of the potentially large economic costs of policy, regulatory, and legal impediments to stock market development.

Is there really a link between stock market liquidity and economic growth, or is stock market liquidity just highly correlated with some nonfinancial factor that is the true cause of economic growth? Multiple regression procedures suggest that stock market liquidity helps forecast economic growth even after accounting for a variety of nonfinancial factors that influence economic growth. After controlling for inflation, fiscal policy, political stability, education, the efficiency of the legal system, exchange rate policy, and openness to international trade, stock market liquidity is still a reliable indicator of future long-term growth.

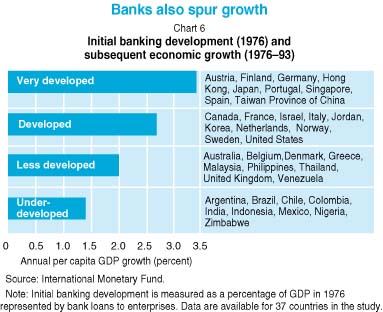

Is there an independent link between stock market development and growth, or is stock market liquidity correlated with banking development--and is the latter the financial factor that really spurs economic growth? Although countries with well-developed banks--as measured by total bank loans to private enterprises as a share of GDP--tend to grow faster than countries with underdeveloped banks (Chart 6), the effects of banks on growth can be separated from those of stock markets.

To evaluate the relationship between stock markets, banks, and growth, our 38 sample countries were divided into four groups. Group 1 had greater-than-median stock market liquidity (as measured by the value-traded-to-GDP ratio) in 1976 and greater-than-median banking development. Group 2 had liquid stock markets in 1976 but less-than-median banking development. Group 3 had less-than-median stock market liquidity in 1976 but well-developed banks. Group 4 had illiquid stock markets in 1976 and less-than-median banking development.

Countries with both liquid stock markets and well-developed banks grew much faster than countries with both illiquid markets and underdeveloped banks. Furthermore, greater stock market liquidity is associated with faster future growth no matter what the level of banking development. Similarly, greater banking development implies faster growth no matter what the level of stock market liquidity. Thus, it is not a question of stock market development versus banking development--each, on its own, is a strong predictor of future economic growth.

Why might stock markets and banks both, independently of each other, boost economic growth? Although the empirical evidence is consistent with the view that stock markets and banks promote economic growth independently of each other, the reasons are not fully understood. One argument is that stock markets and banks provide different types of financial services. Stock markets offer opportunities primarily for trading risk and boosting liquidity; in contrast, banks focus on establishing long-term relationships with firms because they seek to acquire information about projects and managers and enhance corporate control. (There is, of course, some overlap. Like stock markets, banks help savers diversify risk and provide liquid deposits. Like banks, stock markets may stimulate the acquisition of information about firms, because investors want to make a profit by identifying undervalued stocks to invest in; stock markets may also help improve corporate governance by simplifying takeovers, providing an incentive to improve managerial competency.)

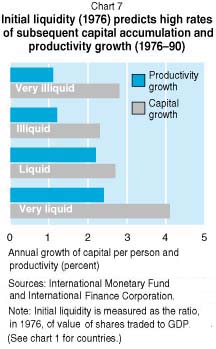

Is greater stock market liquidity associated with more or better investment? Both. Chart 7 shows that countries that had more liquid stock markets in 1976 enjoyed both faster rates of capital accumulation and greater productivity gains over the next 18 years.

However, although liquid equity markets imply more investment, new equity sales are not the only source of finance for this increased investment. Most corporate capital creation is financed by retained earnings and bank loans. Although this phenomenon is not wholly understood, greater stock market liquidity in developing countries is linked to a rise in the amount of capital raised through bonds and bank loans, so that corporate debt-equity ratios rise with market liquidity. Stock markets tend to complement--not replace--bank lending and bond issues.

Given the important role well-functioning

stock markets seem to play in economic growth, what can countries do to promote them?

Fully answering this question is well beyond the scope of any single article. Legal,

regulatory, accounting, tax, and supervisory systems influence stock market liquidity. The

efficiency of trading systems determines the ease and confidence with which investors can

buy and sell their shares. And the macroeconomic and political environments affect market

liquidity.

Given the important role well-functioning

stock markets seem to play in economic growth, what can countries do to promote them?

Fully answering this question is well beyond the scope of any single article. Legal,

regulatory, accounting, tax, and supervisory systems influence stock market liquidity. The

efficiency of trading systems determines the ease and confidence with which investors can

buy and sell their shares. And the macroeconomic and political environments affect market

liquidity.

Consider the impact of one particular policy lever: liberalizing controls on international capital flows. Liberalization may involve easing restrictions on capital inflows or reducing impediments to repatriating dividends or capital. In either case, reducing barriers to cross-border capital flows can affect the functioning of emerging stock markets: first, by enhancing the integration of emerging markets into world capital markets, thereby bringing the prices of domestic securities into line with those elsewhere; and, second, by forcing domestic firms seeking foreign investment to upgrade their information disclosure policies and accounting systems. Moreover, the entry of more foreign investors into emerging markets may lead to pressure to upgrade trading systems and modify legal systems to support more trading and the introduction of a greater variety of financial instruments.

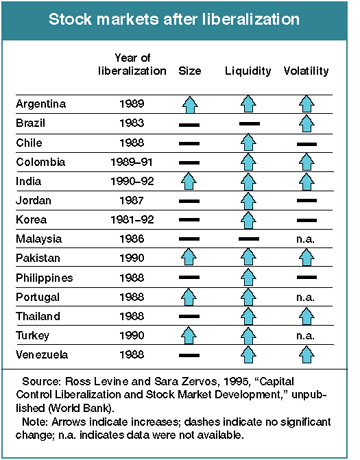

Through all of these channels, the removal of barriers to foreign investment can improve the operation of domestic capital markets. This is consistent with recent evidence. As shown in the table, stock market liquidity rose significantly in 12 out of 14 countries that liberalized controls on international capital flows. Chile, for example, liberalized restrictions on the repatriation of dividends by foreign investors in January 1988. None of the 14 countries experienced a statistically significant drop in liquidity following liberalization. In conjunction with the earlier findings that market liquidity boosts economic growth, these results suggest that liberalizing international capital flow restrictions can accelerate economic growth by enhancing stock market liquidity.

The table also indicates, however, that stock market volatility rose in 7 out of 11 countries following liberalization. Volatility did not fall significantly in any of the 11 countries following liberalization. Thus, while easing international capital flow restrictions may increase liquidity, it may also increase volatility. This should not be of much concern in the long run, however. As shown in Chart 5, volatility does not have any measurable effect on long-term growth. Thus, if policymakers have the patience to weather some short-run volatility, liberalization offers expanded opportunities for long-run economic growth.

Does every country need an active stock market of its own? Unfortunately, there is not much evidence available to answer this question. In principle, all countries do not need domestic stock markets. They do, however, need easy access to liquid stock markets where residents and domestic firms can buy, sell, and issue securities. It is the ability to trade and issue securities easily that facilitates long-term growth, not the physical location of the market. In other words, there is little reason to believe that California would grow faster if the New York Stock Exchange were moved to Los Angeles.

When should policymakers really push stock market development? This is even more uncertain. The available information suggests that policymakers should remove impediments--tax, legal, and regulatory barriers--to stock market development. But there is not strong evidence to support interventionist policies--like tax incentives--that artificially boost stock market size and activity.

While much work remains to be done, a growing body of evidence suggests that stock markets are not merely casinos where players come to place bets. Stock markets provide services to the nonfinancial economy that are crucial for long-term economic development. The ability to trade securities easily may facilitate investment, promote the efficient allocation of capital, and stimulate long-term economic growth. Furthermore, the evidence suggests that stock market liquidity encourages--or at least strongly forecasts--corporate investment, even though much of this investment is financed through retained earnings, bank loans, and bonds, rather than equity issues. Policymakers should consider reducing impediments to stock market development. Easing restrictions on international capital flows would be a good place to start.

This article is based on 12 papers presented at a World Bank conference, "Stock Markets, Corporate Finance, and Economic Growth," organized by Asli Demirgüç-Kunt and Ross Levine. These papers are available from the author on request.