Unemployment, Structural Change and Globalization

M. Pianta and M. Vivarelli

UNEMPLOYMENT AND TECHNICAL CHANGE

by M. Vivarelli

1. Introduction.

The diffusion of the Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) has risen again the old classical debate about the relationship between technology and employment. The fear is that ICT technologies have weakened - or even eliminated - the positive correlation between growth and employment which was undoubtedly one of the main characteristics of the Fordist "golden age" (see Jenkins-Sherman, 1979; Noble, 1984; Aronowitz-DiFazio, 1994; Rifkin, 1995). In some cases, this fear is even translated in future scenarios where "the end of work" is forecast as a possible outcome of a labour-saving relationship between technology and employment. On the whole, this pessimistic literature is characterised by two common features which can be sum up as follows.

On the one hand, the focus of the analysis is confined to the study of the direct labour-saving effect of ICT process innovations and the empirical evidence discussed is often anecdotal: on the one hand, case-studies where dramatic decreases in employment have occurred are proposed as examples of the entire economy; on the other hand, the direct labour-saving impact is proposed as the only consequence of technical change (see Rifkin, 1995).

On the other hand, the methodology of the analysis underestimates the indirect effects of technical change and the unpredictable job opportunities which can be opened by new ICT products. From a static viewpoint, it is very easy to point out the adverse impact of labour-saving innovation, but, from a dynamic perspective, all the compensatory effects of process innovation and all the expansive impacts of product innovation have to be taken into account.

Since from its very beginning, in fact, the economic theory has pointed out the existence of economic forces which can spontaneously compensate for the reduction in employment due to technological progress. The next section will be devoted to the discussion of a "classical taxonomy", which is believed to be of some help in understanding present forms of technical change. In the light of this taxonomy, Section 3 will discuss some open issues which are strictly linked to the introduction and diffusion of ICT.

2. The economics of technology and employment

Is there a relationship between technical change and the demand for labour (Ricardian unemployment) or unemployment is entirely determined by aggregate demand (Keynesian unemployment, see Unemployment and Aggregate Demand) and wage dynamics (Classical unemployment, see Unemployment and Wages)?

As a matter of fact, mainstream economics tends to neglect the possibility of technological unemployment, being technical change generally taken as exogenous and unemployment generally studied as a short-term phenomenon rather than a structural problem. In fact, the economic discipline - since its foundation - has tried to dispel all concerns about the harmful effects of technical "progress". Thus, in the first half of the XIX century - while the Luddites were destroying the new machines, economists put forward a theory that Marx later called the "compensation theory" (see Marx, 1961, vol.1, chap. 13 and 1969, chap. 18). This theory is made up of different market compensation mechanisms which are triggered by technical change itself and which can counterbalance the initial labour-saving impact of process innovation (for an extensive analysis, see also Vivarelli, 1995, chap.3).

The same process innovations which displace workers in the user industries, create new jobs in the capital sectors where the new machines are produced.

On the one hand, process innovations involve the displacement of workers; on the other hand, these innovations themselves lead to a decrease in the unit costs of production and - in a competitive market - this effect is translated into decreasing prices; in turn, decreasing prices stimulate a new demand for products and so additional production and employment. This mechanism was singled out at the very beginning of the history of the economic thought and this line of reasoning became the cornerstone of the compensation theory when the Say's law became the cornerstone of the classical economic theory; according to this law, in a competitive world, the supply generates its own demand and technical change fully takes part in this self-adjusting process.

The compensation mechanism "via decrease in prices" has been re-proposed both by neo-classical economists at the beginning of this century and by modern theorists (for a summary, see Stoneman, 1983 chaps. 11 and 12; for a detailed analysis of the hypotheses, procedures and conclusions of these models, see Vivarelli, 1995, chaps. 4 and 6).

In a world where the competitive convergence is not instantaneous, it is observed that during the gap between the decrease in costs - due to technical progress - and the consequent fall in prices, extra-profits may be accumulated by the innovative entrepreneurs. These profits are invested and so new productions and new jobs are created.

As with other forms of unemployment, the direct effect of labour-saving technologies may be compensated within the labour market through a proper price adjustment. In a neoclassical framework - with free competition and full substitutability between labour and capital - a decrease in wages leads to an increase in the demand for labour (see Layard-Nickell, 1985 and Layard-Nickell-Jackman, 1991 and 1994).

Directly in contrast with the previous one, another compensation mechanism has been put forward by the Keynesian and Kaldorian tradition (see also Vivarelli, 1995, chap.5). In a Fordist mode of production, unions take part in the distribution of the fruits of technical progress. So it has to be taken into account that a portion of the cost savings due to technical change can be translated into higher income and hence higher consumption. This increase in demand leads to an increase in employment which may compensate the initial job losses due to process innovations (see Pasinetti, 1981).

Technical change is not equivalent to process innovation, but it can assume the form of creation and commercialisation of new products; in this case, new economic branches develop and additional jobs are created. Once again, the labour-intensive impact of product innovations was underlined by classical economists and even the most severe critic of the compensation theory admitted the positive employment benefits that can derive from this kind of technical progress (Marx, 1961, vol. I, p.445).

In the current debate, various studies (Freeman-Clark-Soete, 1982; Freeman-Soete, 1987; Freeman-Soete, 1994; Vivarelli, 1995) agree that product innovations have a positive impact on employment since they open the way to the development of either entire new goods or main differentiations of mature goods. In the latter case, the "welfare effect" (new branches of production) has to be compared with the "substitution effect" (displacement of mature products; see Katsoulacos 1986).

As it can be seen even from this short survey of the compensation theory, technical change induces a lot of market forces which can potentially counterbalance the initial labour- saving effect of process innovation. Moreover, decreasing prices due to process innovation and the diffusion of product innovation have a big impact on international competitiveness and so compensation also operates through foreign markets' additional demand.

On the other hand, compensation mechanisms can be hindered by the existence of strong drawbacks which are often either neglected or mis-specified by the conventional economic wisdom. Using the same taxonomy which has been proposed above, the main criticisms of the compensation theory can be singled out as follows.

With few exceptions, nowadays the compensation mechanism "via new machines" is not put forward anymore. Indeed, Marx's critique of this mechanism was so sharp that it stopped this first line of reasoning of the compensation theory. Here is what he said: "...the machine can only be employed profitably, if it...is the (annual) product of far fewer men than it replaces." (Marx, 1969, p.552)

Moreover, labour-saving technologies spread around in the capital good sector, as well; so this compensation is an endless story which can be only partial (Marx, 1969, p.551). Finally, the new machines can be implemented either through additional investments or simply by substitution of the obsolete ones (scrapping). In the latter case - which is indeed the most frequent one - there is no compensation at all (Freeman - Clark - Soete, 1982, p.160).

The mechanism "via decrease in prices" relies on Say's law and does not take into account that demand constraints might occur. Difficulties concerning the components of the "effective demand" - in Keynes' terms - such as pessimistic expectations - can involve a delay in expenditure decisions and a lower demand elasticity. If such is the case, this compensation mechanism is hindered and technological unemployment ceases to be a temporary problem (for a detailed criticism about compensation based on Say's law, see also Standing, 1984, pp.131-133).

Finally, the effectiveness of the mechanism "via decrease in prices" depends on the hypothesis of perfect competition. If an oligopolistic regime is dominant, the whole compensation is strongly weakened since cost savings are not necessarily and entirely translated into decreasing prices (see Sylos Labini, 1969, p.160).

Also the compensation mechanism "via new investments" relies on the Say 's law assumption that the accumulated profits due to technical change are entirely and immediately translated into additional investments. Again, Marx's and Keynes's treatment of Say's law can be used against the full reliability of this compensation mechanism. Moreover, the intrinsic nature of the new investments does matter; if these are capital-intensive, compensation can only be partial (Marx, 1961, vol. I, p.628).

Also the mechanism "via decrease in wages" collides with the Keynesian theory of effective demand. On the one hand, a decrease in wages can induce firms to hire additional workers, but - on the other hand - the decreased aggregate demand lowers the employers' expectations and so they tend to hire less workers.

During the "golden age" of the '50s and '60s the Fordist mode of production was based on an important change in the labour-wage nexus. Instead of leaving the wage to be regulated by a competitive labour-market, workers were allowed to take possession of a relevant portion of productivity gains due to technical progress. In turn, the increased real wages involved mass consumption and this stimulated investments leading to further productivity gains through technical progress and scale economies (Boyer, 1988A and 1988B). Labour-saving technologies were introduced on large scale, but the "Fordism" allowed an important compensation "via new incomes".

Nowadays, in many industrialised economies, the Fordist mode of production is over for many reasons that cannot be discussed here (see Boyer 1988A, Vivarelli, 1995, pp. 83-87). The distribution of income follows different rules and the labour market has returned to be competitive. On the whole, this compensation mechanism has been strongly weakened in the new institutional context.

New products are still the more powerful way to counterbalance labour-saving process innovations. Yet, different "technological paradigms" (see Dosi, 1982) are characterised by different clusters of new products which in turn have very different impacts on employment. So, the introduction of the automobile had a much higher labour intensive effect than the diffusion of the home computers. As a matter of fact, in different historical periods and different institutional frameworks, the relative balance between the labour-saving effect of process innovations and the labour-intensive impact of product innovations can considerably vary.

On the whole, the different mechanisms of the compensation theory form a very complex picture where there are a lot of ways for counterbalancing the direct labour-saving effect, but also a lot of possible drawbacks and hindrances. Economists sometimes forget that compensation can only be partial and that it is dependent on particular structural, historical and institutional circumstances.

3. Employment and technology in the ICT era

The "classical taxonomy" discussed above can also be applied to the present forms of technical change and particularly to the introduction and diffusion of ICT. In more detail, there is a recent concern that ICT can involve lower employment coefficients and so weaken the traditional positive correlation between growth and employment. These observations should be particularly important in manufacturing, where labour-saving ICT process innovation seem to prevail over labour-intensive ICT product innovation. In other words, in recent times, the compensation mechanism "via new products" takes the form of a compensation "via new services". Indeed, the ICT revolution has implied the fastest employment growth rates in services and particularly in the software and information services: "We shall take the example of software employment to illustrate the general problem of assessing the future potential impact of ICT on employment growth. Employment in software and information services was one of the fastest growing categories in all OECD countries in the 1980s" (Freeman-Soete, 1994, p.60).

On the other hand, in manufacturing the ICT revolution seems to be characterised mainly by labour-saving process innovation which are embodied in investment and scrapping. In this context, the substitution of older equipment - either mechanical or electrical - with new one - electronical - generally implies a dramatic decrease in labour coefficients. This is also true in the ICT industries: an important example being the telecommunication industry; in that sector, the transition from electromechanical to electronic switching has implied dramatic cuts in employment levels (see Frey-Vivarelli, 1991).

It is important to notice that ICT labour-saving technologies are continuously introduced through scrapping, and when labour-saving innovation are dominant: "....scrapping of the older equipment will in general necessitate an investment expenditure greater than the replacement value of the scrapped capital if employment levels are to be maintained." (Freeman-Clark-Soete, 1982, p.160). Nevertheless, although the mechanisms via "new machines" and via "new investments" can be severely weakened by the presence of a labour-saving embodied technical change, all the other compensation mechanisms keep on being important also in the ICT era.

In this context, even in manufacturing, new productions have started in the ‘70s and following decades: home computers and hardware, fax, network infrastructures for new ICT services (thinks about optical fibers and ISDN), video recorders and video tapes, CD’s, mobile phones, etc. Thus, although the mechanism "via new products" mainly operates "via new services", manufacturing is not immune by the positive employment impact triggered by the diffusion of new products.

In the meantime, both in manufacturing and services, labour-saving technologies imply decreasing prices and increasing demand, especially through international competition. As discussed in the previous section, this mechanism can be hindered by different institutional rigidities (such as low competition in the fgood markets); yet, some studies on the subject have revealed that this mechanism can be particularly effective even in different institutional contexts, although it does not seem to be able to assure complete compensation (see Vivarelli, 1995, chaps. 8 and 9).

On the whole, the net employment impact of ICT technologies depends on the balance between process and product (service) innovation and on the effectiveness of different compensation mechanisms. Different "national systems of innovation" can reveal different overall impacts according to the sectorial composition of their economies, the different proportion of process and product innovation and the different effectiveness of the compensation mechanisms.

Empirical evidence

Given the framework described in the previous sections, the net employment impact of ICT technologies may be different in different "national systems of innovation". For instance, in a study on the period 1960-1990 (see Vivarelli 1995) the U.S. economy turned out to be more product oriented (and so characterized by a positive relationship between technology and employment) than the Italian economy where different compensation mechanisms cannot counterbalance the labour-saving effect of prevailing process innovation.

In more general terms, the overall impact of technologies on employment levels can be assessed in two alternative ways. On the one hand, attention can be focused on the long-run direct relationship between technology and employment, in order to detect whether is technical change associated with a long-run decline in the demand for labour. On the other hand, the issue can be treated in a more indirect way: in this case, the point is whether has technological diffusion negatively influenced the correlation between output growth and employment (jobless growth hypothesis).

Indeed, there are well-known difficulties in measuring aggregate technical change and its direct employment impact. On the one hand, proxies for technical change are always unsatisfactory: R&D expenditures are only a measure of innovation input (which can or cannot involve actual innovation), while patent data do not distinguish radical innovation with large employment effects from minor innovation with a very limited impact. On the other hand, only few countries have data directly concerning major innovations. For these reasons, the empirical evidence presented here tries to assess the role of technology in an indirect way, looking at the long term relationship between growth (of real GDP) and employment in different countries. From this comparison it will be possible to show the labour-intensity of growth: given a 100% increase in real GDP, how much does employment increase (this measure is called elasticity and it is the ratio between the long-run change in real GDP and the long-run change in employment)? National differences in elasticities can be explained by the nature of technology and compensation within the different countries: thus, countries characterized by labour-saving process innovation and slow and ineffective compensation mechanisms will have low (or even negative) employment elasticities, while countries focusing on product innovation and exhibiting powerful compensation mechanisms will present higher employment elasticities, that is a higher capacity of job creation, given a certain rate of growth.

From an empirical point of view, the question is to see whether has technology implied a general tendency towards the saving of work. It is important to stress that this exercise has to be conducted in terms of total annual hours of work, since the focus of the analysis is the total need of work which is requested by a given economic system. Thus, for this aim, both unemployment and employment statistics are obviously misleading since the first is biased by the relative dynamics of labour supply and labour demand, while both of them do not take into account the general trend towards a continuous decrease of working time per employee. This general trend has nothing to do with the market compensation mechanisms which have been discussed so far and it obviously involves a bias: if, for instance, labour-saving technologies has implied a decrease of 20% in the labour coefficients and the annual per-capita working time has decreased by the same percentage, the comparison in terms of employment (number of employees) would erroneously lead to the conclusion of a neutral employment impact of innovation. Hence, for the purpose of assessing the impact of technological change on the total need of work, the total amount of hours of work in a given economic system has to be used as the proper employment indicator (annual per-capita average working time times the number of full-time equivalents employees).

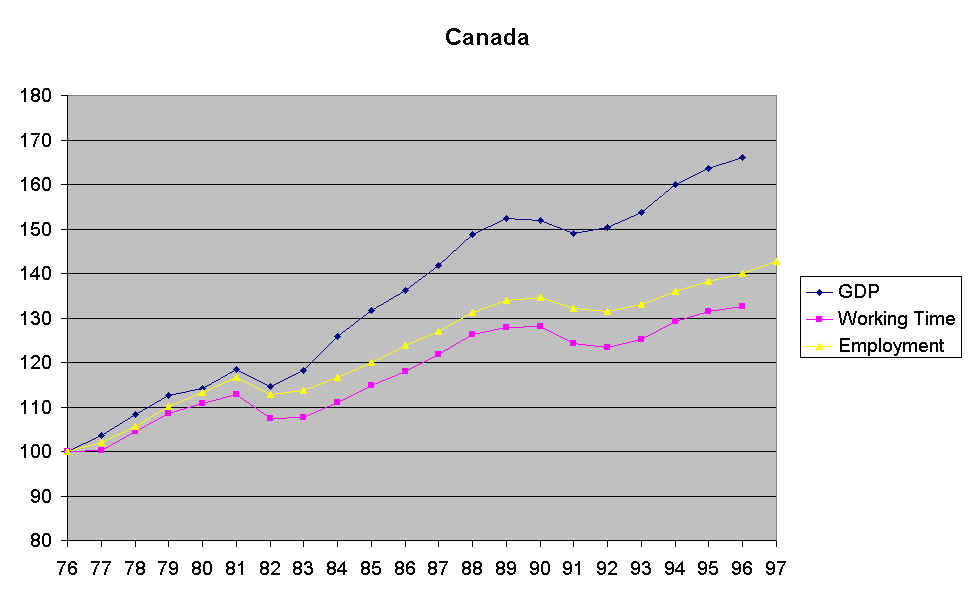

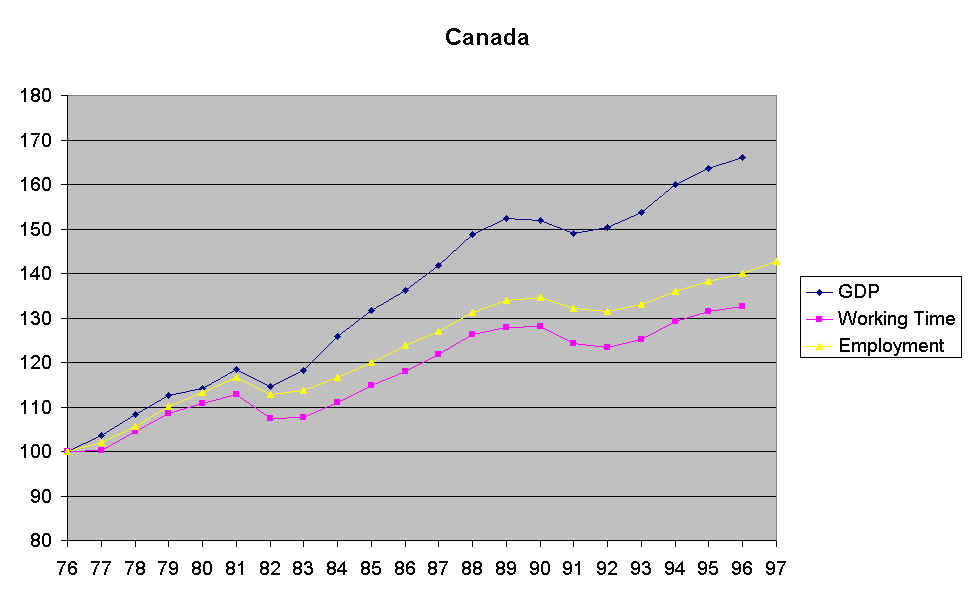

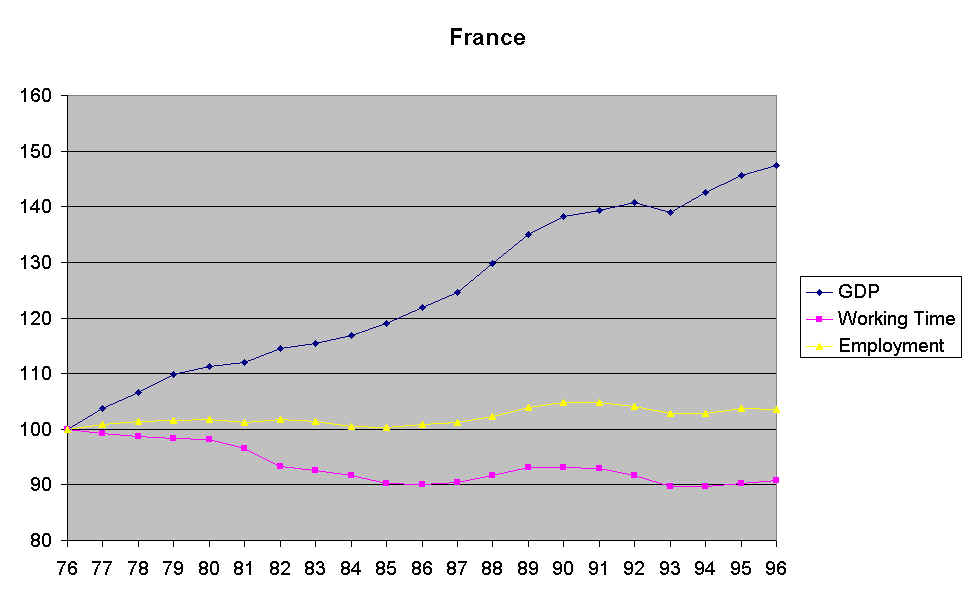

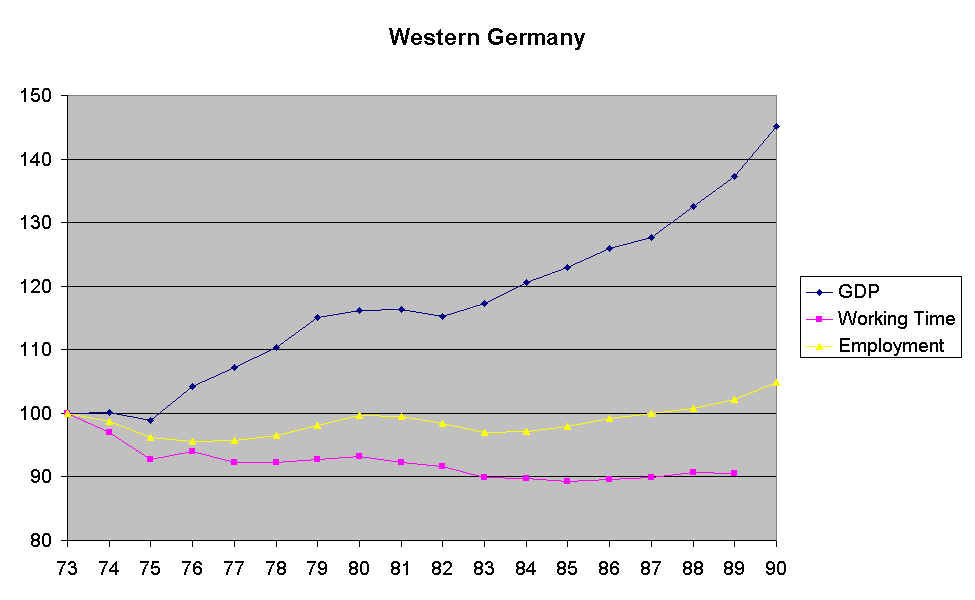

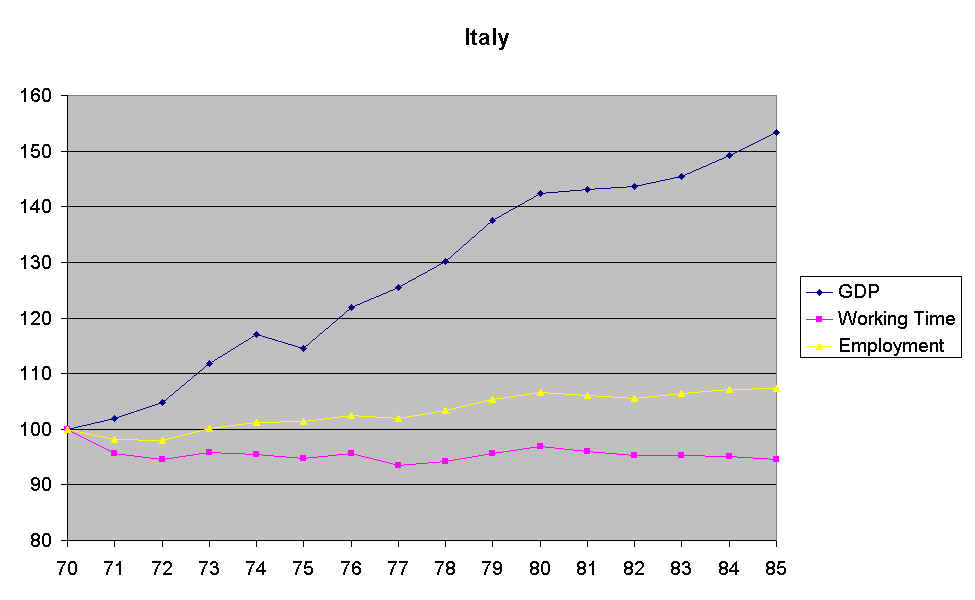

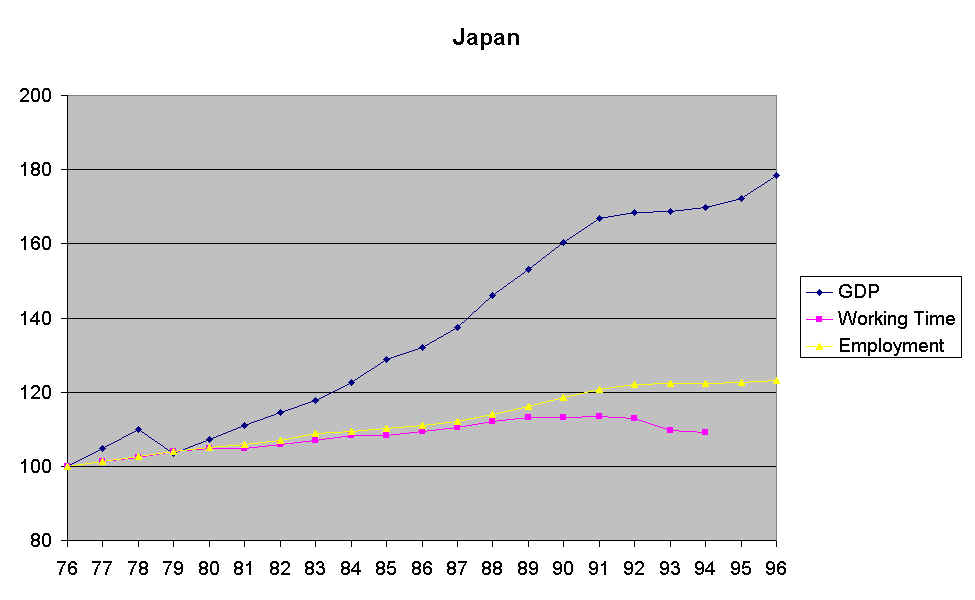

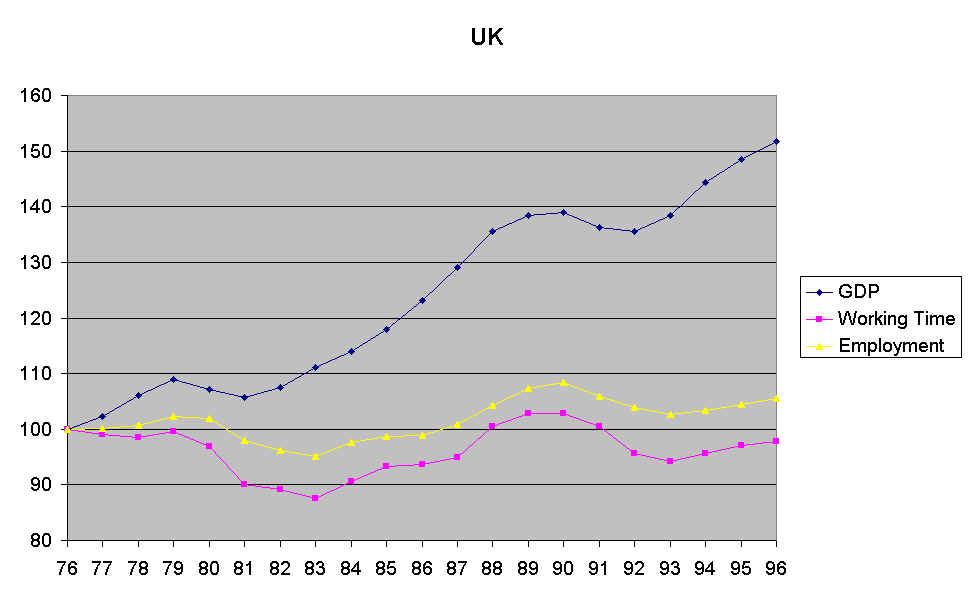

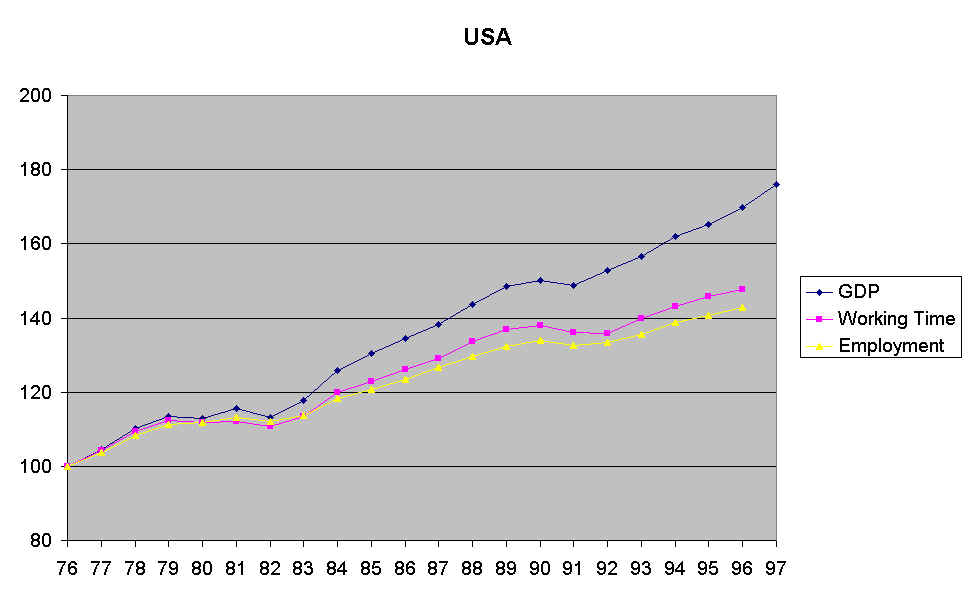

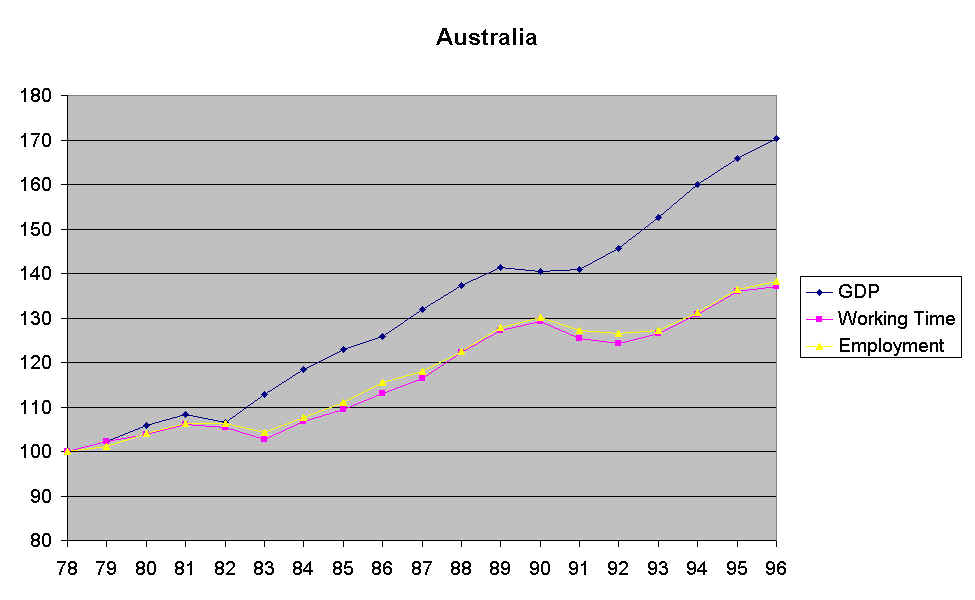

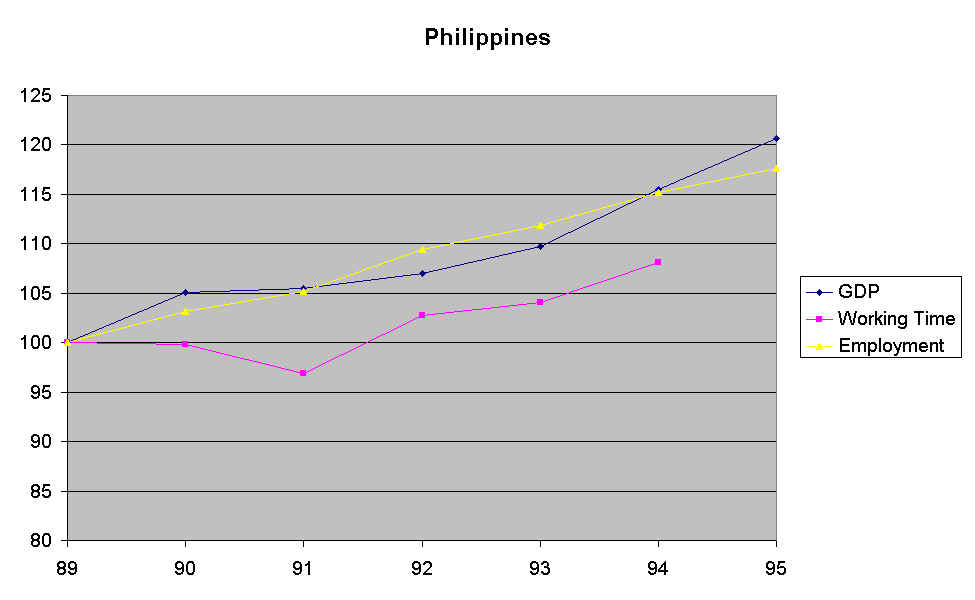

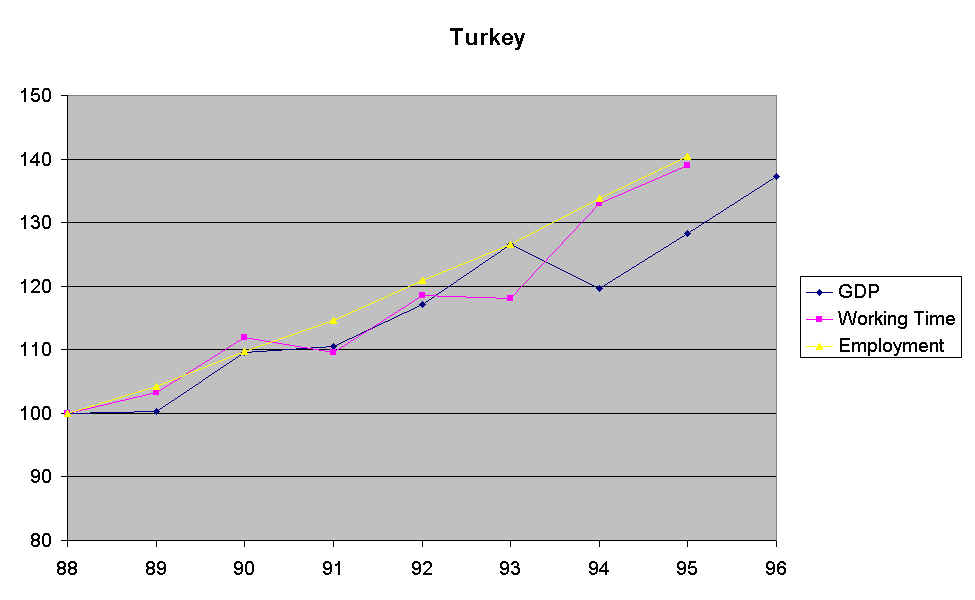

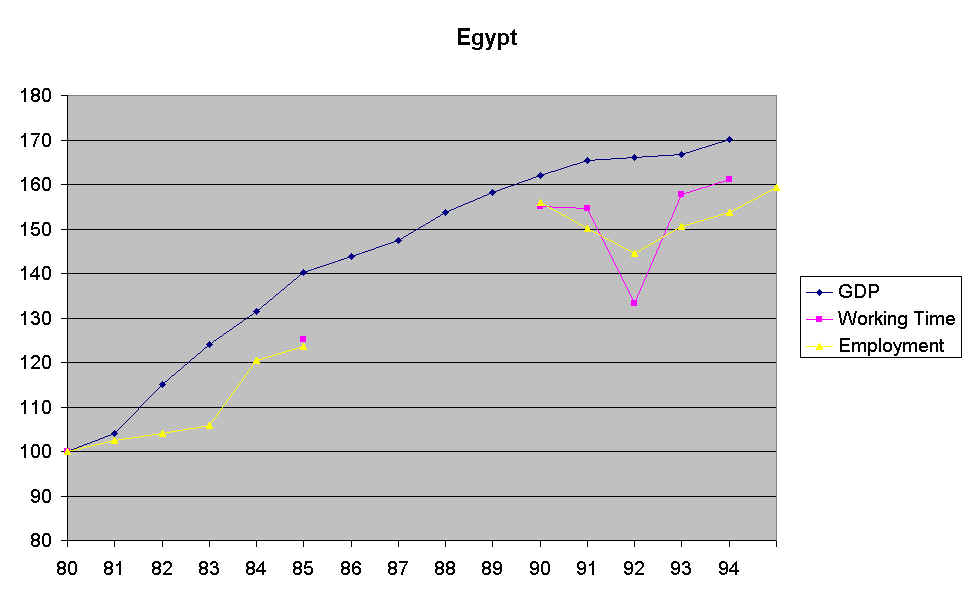

In the following graphs normalized real GDP, employment and total working time trends are compared for the US, Canada, Australia, Japan, West Germany, Italy, France, the UK, Philippines, Turkey and Egypt. Countries have been selected according to their relative importance in terms of population and according to the availability and reliability of data.

As it can be easily seen, a striking difference emerge between European countries and extra-European countries: indeed, the correlation between growth and the increased need of working time holds only in the extra-European countries (these results confirm previous empirical evidence collected in Padalino-Vivarelli, 1997). In the four main European countries GDP growth is coupled with employment stagnation and with a long-run decline in total working time. This means that European countries are characterized by lower technical coefficients, that this by a long-run labour-saving employment bias. Thanks to the reduction of per-capita working time, this tendency does not imply mass unemployment; however, jobless growth seems clearly to emerge in European countries.

This is not the case in extra-European Anglo-Saxon countries where economic growth is still accompanied by positive trends both in employment and total working time. Japan lies in an intermediate position with economic growth coupled with a very moderate growth in total working time. Graphs for the three newly industrialized countries present scattered evidence because of lack of data; at any rate, a positive link between real GDP growth and both employment and working time seems to characterize the three reported cases.

This analysis can be deepened by computing the long-run working time elasticity (the ratio between the working time differential and the real GDP growth) over the examined periods. In the following table the overall rates of change of real GDP and total working time together with the correlated elasticities are reported.

Table 1: Long Run Percentage Changes for the Whole Economy

|

|

US |

Japan |

Canada |

Australia |

|

Real GDP (=a) |

69,97 |

69,92 |

66,00 |

70,35 |

|

Total Working Time (=b) |

47,70 |

9,2 |

32,64 |

37,02 |

|

Elasticity (=b/a) |

68,47 |

13,16 |

49,45 |

52,61 |

|

Time Interval |

1976-1996 |

1976-1994 |

1976-1996 |

1978-1996 |

|

|

West Germany |

Italy |

France |

UK |

EU15 |

|

Real GDP (=a) |

45,1 |

53,34 |

47,49 |

51,78 |

52,45 |

|

Total Working Time (=b) |

-9,27 |

-5,44 |

-8,63 |

-2,20 |

|

|

Elasticity (=b/a) |

-20,55 |

-10,2 |

-18,18 |

-4,24 |

|

|

Time Interval |

1973-1990 |

1970-1985 |

1976-1996 |

1976-1996 |

1976-1996 |

|

|

India |

Philippines |

Mexico |

Turkey |

South Africa |

Egypt |

|

Real GDP (=a) |

|

15,45 |

|

28,28 |

|

70,16 |

|

Total Working Time (=b) |

|

8,07 |

|

38,94 |

|

61,18 |

|

Elasticity (=b/a) |

|

52,25 |

|

137,69 |

|

87,21 |

|

Time Interval |

|

1989-1994 |

|

1988-1995 |

|

1980-1994 |

Real GDP: OECD National Accounts for Canada, Australia, West Germany, Italy, France, EU 15, Turkey;

Data Stream for US, Japan, UK;

African Statistical Yearbook for Egypt;

Asian Statistical Yearbook for Philippines.

Working Time: the series is computed as the product of average yearly hours of work (or weekly average hours of work multiplied by the number of weeks worked in the year) and total employment. Part-time employment is taken into account in the calculus of average hours of work.

Average yearly hours of work:

Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Labour Force Survey. |

Canada: New data series supplied by Statistics Canada, based mainly on the monthly Labour Force Survey. |

France: Data supplied by Institut National de la Statistique et des Études Économiques. |

Germany: Data supplied by the Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung, |

Italy: Data for total employment provided by ISTAT. |

Japan: Statistics Bureau, Management and Coordination Agency, Tokyo from the Monthly Labour Survey |

United Kingdom: Figures refer to Great Britain; annual Labour Force Survey. |

United States: Data supplied by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. |

Average Weekly Hours of Work:

Philippines, Turkey, Egypt: ILO

Employment: Data Stream for Japan, Italy, France, Canada.

OECD National Accounts for UK and West Germany

ILO for US, Australia, Turkey, Egypt, Philippines, India, Mexico

All the eight industrialized countries exhibit comparable rates of growth, with Europe a bit lagging behind. Yet, the lower European rates of growth do not explain the poor European performance in terms of demand for working time. As it can be seen, all the European countries show decreasing trends in total working time and overall elasticities ranging from -6.14 (the UK) to -20.55 (West Germany). On the contrary, the three extra European Anglo-Saxon countries clearly show the capacity to combine economic growth with the expansion of the use of working time, while Japan still have a positive, although lower, elasticity. Thus, economic growth is "work intense" in the US, Canada and Australia whilst jobless growth occurs in Europe. This means that the sectorial composition of the different economies and the correlated paces and forms of technical change imply a labour using trajectory in the former countries and a strong labour-saving bias in the European ones. Economic and social policies in Europe should always take into account this adverse characteristic of the European economic systems.

Notwithstanding the availability of shorter time series, the positive link between economic growth and total working time appears to be confirmed also in the Philippines, Turkey and Egypt.

* Useful introductions to the pessimistic view which has been discussed in Section 1 are the following references:

Aronowitz, S. and DiFazio, W. 1994. The Jobless Future: Sci-Tech and the Dogma of Work, Minneapolis-London, University of Minnesota Press

Jenkins, C. and Sherman, B. 1979. The Collapse of Work, London-Fakenham-Reading, Cox & Wyman Ltd

Noble, D.F. 1984. Forces of Production: A Social History of Industrial Automation, New York, Alfred A. Knopf

Rifkin, J. 1995 The End of Work. The Decline of the Global Labour Force and the Dawn of the Post-Market Era, New York, G.P. Putnam's Sons

* In particular, the last and more recent reference has been very influential, especially in the Anglo-Saxon union movement. Yet, the gloomy picture proposed by Rifkin does not seem to apply to industrialized economies and especially the US, where no signs of "end of work" are detectable (see the evidence presented above).

* The most effective way to have a direct knowledge of the classical debate discussed at the beginning of Section 2 is to read Chapter 31 of Ricardo’s Principles, Chapter XIII of the first volume of Marx’s Capital and Chapter XVIII of Marx’s Theories of Surplus Value. A complete review of the classical debate can be found in Vivarelli, 1995 (chap. 3). Other surveys are those made by Standing and Petit.

Ricardo, D. 1951 Principles of Political Economy, in Sraffa, P. (ed.), The Works and Correspondence of David Ricardo, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, vol.1, third edn 1821

Marx, K. 1961. Capital, Moscow, Foreign Languages Publishing House, first edn 1867

Marx, K. 1969. Theories of Surplus Value, London, Lawrence & Wishart, first edn. 1905-10

Petit, P. 1995, Employment and Technological Change, in Stoneman, P. (ed), Handbook of the Economics of Innovation and Technological Chnage, Amsterdam, North Holland, 366-408

Standing, G. 1984. The Notion of Technological Unemployment, International Labour Review, vol. 123,.127-47

Vivarelli, M. 1995. The Economics of Technology and Employment: Theory and Empirical Evidence, Aldershot, Elgar

* The recent economic debate about the impact of technical change is effectively summarized in Stoneman, 1983 (chaps. 11 and 12) and , with a more critical aptitute in Vivarelli, 1995 (chaps. 4,5,6). Quite important are the alternative neo-Keynesian approaches put forward by Sylos Labini and Pasinetti. Notwithstanding the critiques to the compensation theory and the presence of alternative approaches, mainstream economics is still quite confident in the market mechanisms able to fully counterbalance the initial dismissal of workers due to labour-saving technologies. Good examples of an optimistic and a-critical opinion on the subject are the below cited works by Layard-Nickell and Jackman and by the OECD.

Pasinetti, L. 1981. Structural Change and Economic Growth, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Stoneman, P. 1983. The Economic Analysis of Technological Change, Oxford, Oxford University Press

Sylos Labini, P. 1969. Oligopoly and Technical Progress, Cambridge (Mass.), Harvard University Press, first edn 1956

Layard, R. and Nickell, S. 1985. The Causes of British Unemployment, National Institute Economic Review, vol.111, 62-85

Layard, R. - Nickell, S. - Jackman, R. 1991. Unemployment: Macroeconomic Performance and the Labour Market, Oxford, Oxford University Press

OECD 1996. Technology, Productivity and Job Creation, Analytical Report, Paris, OECD

* The following references extend the optimistic approach - based on compensation theory - on the employment impact of innovation to developing countries:

Hall, P.H. and Heffernan, S.A. 1985. More on the Employment Effects of Innovation, Journal of Development Economics, vol.17, 151-62

Heffernan, S.A. 1981. Technological Unemployment, unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Oxford, Oxford University

* A more theoretical approach, aimed in particular to show the different employment impact of process (negative) and product (positive) innovation, is contained in:

Katsoulacos,Y.S.,1986. The Employment Effect of Technical Change,Brighton, Wheatsheaf

* The relationship between technology and employment is embedded in the institutional context; about the role of institutions and the historical shift to post-Fordist society, it is very important the contribution of the so called French "école de la régulation":

Boyer, R. 1988A. Technical Change and the Theory of Régulation, in Dosi, G. - Freeman, C. - Nelson, R. - Silverberg, G. - Soete, L. (eds), Technical Change and the Economic Theory, London, Pinter, 67-94

Boyer, R. 1988B. Formalizing Growth Regimes, in Dosi, G. - Freeman, C. - Nelson, R. - Silverberg, G. - Soete, L. (eds), Technical Change and the Economic Theory, London, Pinter, 608-35

Boyer, R. 1989, The Eighties: The Search for Alternatives to Fordism: a Very Tentative Assessment, working paper CEPREMAP n.8909, Paris

Boyer, R. 1990. The Capital Labor Relations in OECD Countries: from the Fordist "Golden Age" to Contrasted National Trajectories, working paper CEPREMAP n.9020, Paris

* New ICT technologies have some characteristics, such as cumulativeness and irreversability, in common with other technologies and some other, such as pervasiveness and a bias towards labour-saving process innovation, which are more specific. The following references are of some help in theorizing the role of ICT in shaping employment trends.

Dosi, G. 1982. Technological Paradigms and Technological Trajectories, Research Policy, vol.11, 147-63

Dosi, G. 1988. Source, Procedure and Microeconomic Effects of Innovation, Journal of Economic Literature, vol.26, 1120- 71

Freeman, C. - Clark, J. - Soete, L. 1982.Unemployment and Technical Innovation, London Pinter

Freeman, C. and Soete, L. (eds) 1987. Technical Change and Full Employment, Oxford, Basil Blackwell

Freeman, C. and Soete, L. 1994. Work for All or Mass Unemployment? Computerised Technical Change into the Twenty-first Century, London-New York, Pinter

Frey, M and Vivarelli, M. 1991. New Technology and Employment in Italian Telecommunications, Technovation, vol.11, 303-14

* Empirical studies about the relationship between growth and employment and the estimation of the "jobless growth" hypothesis (see section about the empirical evidence) are the following:

Boltho, A. - Glyn, A. , 1995, Can Macroeconomic Policies Raise Unemployment?, International Labour Review, vol.134, 451-70. Glyn, A. 1995, The Assessment: Unemployment and Inequality, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, vol. 11, 1-25. ILO, 1996, World Employment 1996-97: National Policies in a Global Context, Geneva, International Labour Office. |

Padalino, S. - Vivarelli, M. 1997, The Employment Intensity of Economic Growth in the G-7 Countries, International Labour Review, Vol. 136, 191-213. |

Pianta, M. 1995, Technology and Growth in OECD countries, 1979-1990, Cambridge Journal of Economics, Vol. 19, n. 1, 175-87 |

Pianta, M., Evangelista, R. and Perani, G. 1996, The Dynamics Of Innovation and Employment: An International Comparison, Science, Technology Industry Review, N. 18, 67-93 |

With the exception of Padalino-Vivarelli (1997), a common limitation of the studies above is the lack of any indicator in terms of working time (see section on the empirical evidence)