Unemployment, Structural Change and Globalization

M. Pianta and M. Vivarelli

UNEMPLOYMENT

AND THE LABOUR MARKET

by M. Vivarelli

1. Introduction.

Labour economists tend to consider unemployment as a short-term disequilibrium which can be solved by a proper price adjustment, that is by a wage decrease large enough to induce an adequate increase in the demand for labour (see "Unemployment and Wages"). Yet, in recent times, unemployment appears to be a rather permanent phenomenon, especially in the largest European countries and in the European Union as a whole. Moreover, this persistence does not seem to be positively affected by wage moderation started in the late ‘80s and lasting during the ‘90s (see "Unemployment and Wages, Empirical Evidence"). Thus, mainstream economics has tried to find other justifications of high and permanent rates of unemployment and attention has been focused on the so-called "labour market rigidities".

The main thesis is that such rigidities hinder the normal operating of the labour market and so the demand for labour cannot properly respond both to economic expansion and to decreasing wages and hence unemployment becomes a permanent problem.

It has to be noticed that in this way the conventional economic wisdom exits from a traditional short-term perspective and starts to deal with determinants of unemployment other than higher wages. Yet, the analysis is still strictly limited to the labour market and so a "partial equilibrium approach" is fully maintained (see "Unemployment and Wages"). In other words, the theoretical and empirical research stays within the borders of the labour market and other possible determinants of persistent unemployment - such as technology, structural lack of aggregate demand, international competitiveness (see the correspondent entries) - are completely neglected.

So, the focus of the analysis is turned towards those labour market rigidities which can entail long-term unemployment and the so-called "hysteresis" (see Blanchard-Summers, 1986 and 1987; Cross 1987; Graafland, 1991). The main idea of the hysteresis theory is that the current level of unemployment also depends on the past history of unemployment. In particular, duration effects are at work. When high rates of unemployment are combined with a large incidence of long-term unemployment (people unemployed for more than one year), long unemployment duration impairs the human capital of unemployed and so their employability is deeply reduced. In addition, long unemployment duration discourages job search and this fact in turn reinforces the tendency of employers to stigmatize long-term unemployed as low quality workers (see Jackman-Layard, 1991). In this framework, labour rigidities are "bad" not only because they refrain labour demand from increasing but also because low and delayed hiring rates imply an increase in the unemployment duration and so unemployment becomes chronic.

So, different forms of labour market rigidities (see next sections) involve - at time t - an increase in unemployment and especially high rates of long-term unemployment. In turn, a higher proportion of the unemployed being long-term unemployed, and hence demoralized and stigmatized in the eyes of employers, involve a further increase in the overall unemployment rate at time t+1 ("long-term unemployment reduces the effectiveness of the unemployed as potential fillers of vacancies", Layard-Nickell-Jackman, 1991, p.4). In this context, even decreasing wages can be of little help in solving unemployment problems, since hysteresis tends to perpetuate current unemployment trends.

As it can be seen, in this view unemployment is a "path dependent" variable: current rates depend on past rates and to reverse the process results very difficult, especially in presence of high rates of long-term unemployment. Indeed, European countries are characterized by high and persistent unemployment rates and, at the same time, by a high incidence of long-term unemployment while opposite trends and values can be found in the US labour market. So the hysteresis theory and the occurrence of a strong path dependence seem to be confirmed by this empirical comparison (see also the next section about the Empirical Evidence).

Yet, it is disputable that all the causes of increasing unemployment rates and increasing incidence of long-term unemployment can be found in labour market rigidities. This critique will be raised in the conclusive comments (Section 3), while the next section will try to fully explain and articulate the mainstream opinion that labour market rigidities are the main determinants of unemployment rates.

2. Different forms of market rigidities and policy proposals.

In this section different forms of labour market rigidities and correspondent proposals of reforms will be briefly surveyed. In the conventional framework, labour market regulation of recruitment and dismissals has been considered as the most important hindrance at the enterprise level, and as having the largest adverse impact on enterprise performance and employment. For instance, Lazear concludes that severance pays have a "...depressing effect on employment rates, labour force participation and hours of work" (see Lazear, 1990, p.717; see also Bertola, 1990). However, there are also other forms of labour market rigidities which have to be taken into account (for a general orthodox assessment of this topic see OECD 1994a and 1994b).

Hiring costs. In this context, the indicators of labour rigidities which are generally taken into account are the cost of labour associated with a new employee, the regulation and length of probationary periods and the hindrances to a completely free-market recruitment (quotas for handicapped people, employment lists, bureaucratic procedures; see Emerson, 1988). Proposals in this context regard longer probationary periods - especially for more skilled workers in order to minimize the risk of hiring a wrong person for the job - , abolition of the employment lists and simplification of the recruitment procedures. In addition, a temporary exemption from social security taxes for new hiring is a very common way to reduce the cost of labour.

Firing costs. As far as dismissals are concerned, the main issues are the firing restrictions (in some country, like Italy, large firms cannot fire workers without a good reason -"giusta causa"-; while in most countries, included the US, firing is at least submitted to some form of restriction against discrimination, see Piore, 1986), the notice period and the severance pay. Advocates of deregulation call for the complete abolition of firing restrictions, for shorter notice periods and for lower severance pays; otherwise, they argue, firms will continue to be very reluctant to hire workers that they cannot easily get rid of (see Bentolila-Bertola, 1990). Of course, these issues cannot be regarded in isolation without take into account wage setting, unemployment benefits and the overall social security system. For instance , unions might accept lower severance pays in exchange for higher unemployment benefits.

Unemployment benefits. Advocates of deregulation think that higher unemployment benefits discourage job search and so unemployment looses its role of "discipline device" within the labour market (that is to induce lower wages and so an increase in the demand for labour): "...(unemployment) level is subject to a host of distorting influences, tending to make it higher than is economically efficient. The most obvious of these distortions are: 1. the benefit system, which is subject to massive problems of moral hazard (unless administered well), and 2. the system of wage determination,..." (Layard-Nickell-Jackman, 1991, p. 61). In this context, proposals of reforms go from changes in the duration and level of unemployment benefits to the (partial) substitution of unemployment benefits with "employment vouchers" (see Snower, 1994 and 1995).

Temporary contracts. Fixed term job contracts obviously offer a direct opportunity for flexibility for employers by enabling them to hire workers for a limited period of time without assuming any commitment. Here the main reform proposals are the possibility to use this type of contracts without any limitation and the possibility of renewing them an indefinite number of times. Of course, this kind of (de)regulation is closely connected with firing costs; if firing is free, there is no need of stipulate a temporary contract. It has to be noticed that countries where the access to fixed term contracts has been heavily relaxed - such as Spain - do not seem to have reversed their bad unemployment trends.

Working time and part time. Since market demand is variable, the demand for labour would like to be variable as well, both in terms of individuals (see above) and in terms of time. Hence, restriction on daily and weekly hours and overtime regulations result particularly unpleasant to the employers. Also in this case, supporters of the deregulation ask for the exception to collective agreement with regard to working time.

Health and safety at work. While health and safety at work can be costly for the employer, proponents of deregulation think that, at least, health insurance must not be assured to the unemployed in order to give them an additional incentive to an effective job search. In giving his suggestions to the Europeans, the American economist John Pencavel does not hesitate to state: "...Also very important, health insurance for most Americans is tied to their jobs so that a typical unemployed individual loses any health insurance he once had....The lack of medical insurance can be a powerful force pushing the unemployed back to work" (Pencavel, 1994, p.624). It is obvious that this kind of proposals would have an important impact on social welfare and so they have to be considered very cautiously.

Geographical and sectorial mobility. The economic cycle, the international competitiveness and the actual pace of technical change all call for a larger labour mobility both in terms of location and in terms of sectors of activity. Nowadays, labour mobility in the US is approximately four times labour mobility in Europe. Proposals for increasing labour mobility ask for subsidized rents for houses, public incentives to capital mobility, better social infrastructures in order to alleviate the cost of a family transfer (kindergartens, schools, health services, communication, entertainment).

In a short-term and partial analysis it is undeniable than lower wages and a more flexible labour market can entail lower unemployment rates. In the entry "Unemployment and Wages", some powerful objections to wage moderation as the main way to exit from the unemployment problem have been discussed. Here it will be sufficient to present some possible trade-offs between the deregulation of labour market and other economic and social issues. In addition, other possible explanations of increasing unemployment and higher long-term unemployment will be briefly recalled (they are fully discussed in the corresponding entries).

Deadweight and substitution effects. The introduction of some forms of labour market measures may have the simple effect to induce firms to fill their vacancies through temporary contracts instead of permanent ones. If such is the case, deregulation does not imply additional hiring but deadweight (the vacancy would anyway have been filled) and substitution effects (the vacancy would otherwise have been filled through permanent job contracts). For instance, the introduction of deregulation in Spain has implied that turn-over is nowadays covered almost entirely by temporary contracts (see Bentolila-Dolado, 1994; Bentolila-Saint Paul, 1992). It is interesting to note that temporary contracts hardly evolve into permanent jobs: in Spain, after one year of temporary contracts, 59% of employees is still engaged in a temporary contract while only 14% is hired through a permanent one (17,3% is unemployed, 5,1 is out of the labour force and 4,7% is in other situations; see Toharia, 1997).

Deregulation and training. While rigidities within the labour market may deter hiring, they can stimulate training and investment in human capital. In fact, when the job contract is a permanent one, both the employer and the employee fell embedded in a long-term relationship and so the employer has a strong interest to train its labour force, while the employee has a stronger incentive to learn since its present job is reasonably stable. In other words, job stability is a pre-condition for a joint investment which generally rises the quality of the job and implies a long-term commitment by both sides. On the contrary, a highly deregulated labour market with large mobility and a shorter job duration can involve under-investment by the firms, which are afraid of poaching, and lack of motivation by the workers (see, CEPR, 1995, chap. 2.5). If such is the case, labour market deregulation can have positive short-run effects - in terms of employment - but negative long-run countereffects - in terms of human capital and labour productivity.

Deregulation and income inequality. The other side of the coin of a deregulated labour market with lower unemployment rates seems to be a larger inequality. This seems empirically confirmed by the increasing number of working poors in the US and by recent trends in the UK (see Gittleman-Joyce, 1995 and 1996; Gregg-Machin, 1994). Traditionally, more rigid labour markets such as the German one are characterized by lower income inequality and larger income mobility (see Burkhauser-Poupore, 1993; Burkhauser-Holtz-Eakin-Rhody, 1997). For reasons of space, it is here impossible to deal with the complex issue of income inequality; it will sufficient to say that, although many are the determinants of income distribution, labour market deregulation can imply an increase in income inequality. Indeed, cross country comparisons based on the unemployment rates should take into account the working poor phenomenon: from a social point of view, an American family with two parents employed but poor is comparable with an European family where a breadwinner with a stable and high wage job has his/her partner unemployed.

Regulation vs civil law. Through deregulation, contractual agreements and collective arrangements are replaced by market forces; however, deregulation may imply that one mode of regulation is simply replaced by another: civil law. If such is the case, the advantages of deregulation have to be compared with the disadvantages of a greater reliance on the courts, both in terms of additional costs and unpredictable outcomes.

Unemployment vs uncertainty. Even from a pure neo-classical and utilitarian point of view, higher stability coupled with higher unemployment could be the outcome of a maximizing choice. As it is well-known (Rosen, 1985) workers are risk averse and so they do not like instability and uncertainty; once again, from a social point of view, it is hard to consider a situation with shorter unemployment spells and shorter job duration preferable to a situation characterized by longer unemployment spells and higher job stability. In other words, a young European worker might prefer to wait two years to get a job, but to get a stable job rather than to wait one month and to get a temporary short-term job. Similarly, an adult European worker might prefer to bare a reasonable risk to become long-term unemployed rather than afford the risk to change job and location every two or three years. Also from this respect, simple cross-country comparisons of official unemployment rates are very poor indicators of social welfare.

"Rush to the bottom". Deregulation can trigger an endless "rush to the bottom" in labour market regulatory standards. The demand for flexibility by firms is potentially infinite and competitiveness through open labour markets can involve a continuous dismantling of labour rights and welfare systems. Once again, short-run imperatives have to be carefully balanced by long-run considerations in terms of basic labour standards, equity and social cohesion.

Other possible causes of "structural unemployment". While mainstream economics calls "structural unemployment" that portion of unemployment which is thought to be due to market rigidities, there are alternative ways to investigate the permanence of high unemployment rates and increasing long-term unemployment. As it is diffusely discussed in other entries, a prolonged lack of aggregate demand (such as that experimented in Europe after Maastricht’s agreement), a labour-saving biased technical change, a labour-unfriendly international specialization are all possible alternative causes of high and permanent unemployment rates.

Empirical evidence

From an empirical point of view, the impact of deregulation in terms of employment performance is quite doubtful. In particular, European employment performance - measured both in terms of higher employment rates and reduced unemployment - has not increased since deregulation began (the starting point being the second half of the ‘80s for some country and the early ‘90s for other). In addition, within Europe, some countries which have deregulated more in relative terms, such as Spain and recently Italy (see Pacelli-Rapiti-Revelli, 1995) have not experienced an appreciable decrease in their unemployment rates. On the other hand, the European advocates of deregulation tend to emphasize both the recent good results of the UK , Ireland and the Netherlands and the fact that some countries like Italy have still to "cross the river" : "...some European labour markets may currently be ‘in the middle of the river’: they already experience the negative employment aspects of an ‘American’ labour market...without yet enjoying its benefits - unemployment reduction through wage adjustments and worker mobility across regions, sectors and occupations" (Bertola-Ichino, 1995, p.362); thus, the transition to more flexible labour market institutions should be drastic and fast: "If a flexibility-oriented reform is not fully credible, the behaviour of firms and workers in a dynamic labour market, where expectations have an important role, may generate dangerous self-fulfilling prophecies." (ibidem, p.414).

At any rate, at least till nowadays, it is very hard to find out a clear correlation between deregulation and employment performance. In the next table a "rigidity ranking" is reported (source: OECD, 1994a; the overall indicator of "strictness" is an average of four different indicators which are described in the table). As it can be seen, till the early ‘90s the US labour market was the most flexible in the world, followed by Canada and by the two Oceanian countries. Among European countries, the most flexible are the UK and, in continental Europe, Denmark and Switzerland. Japan is in an intermediate position, while all the rest of continental Europe follows behind. Within continental Europe, Southern countries are the most rigid, while the Netherlands, Ireland and - surprisingly - nordic countries appears more flexible than France and Germany.

Table 1: ranking of the degree of rigidity in the labour market

|

Country |

Indicator of the "strictness" of the labour market |

|

US |

1 |

|

New Zealand |

2 |

|

Canada |

3 |

|

Australia |

4 |

|

Denmark |

5 |

|

Switzerland |

6 |

|

UK |

7 |

|

Japan |

8 |

|

Netherlands |

9 |

|

Finland |

10 |

|

Norway |

11 |

|

Ireland |

12 |

|

Sweden |

13 |

|

France |

14 |

|

Germany |

15 |

|

Austria |

16 |

|

Belgium |

17 |

|

Greece |

18 |

|

Portugal |

19 |

|

Spain |

20 |

|

Italy |

21 |

|

Source: OECD Jobs Study (1994), Table 6.7. This

indicator provides a ranking of the grade of "strictness" of the labour market; Note: data for unemployment (total and long term) refer to 1993, except for Germany (1990) |

|

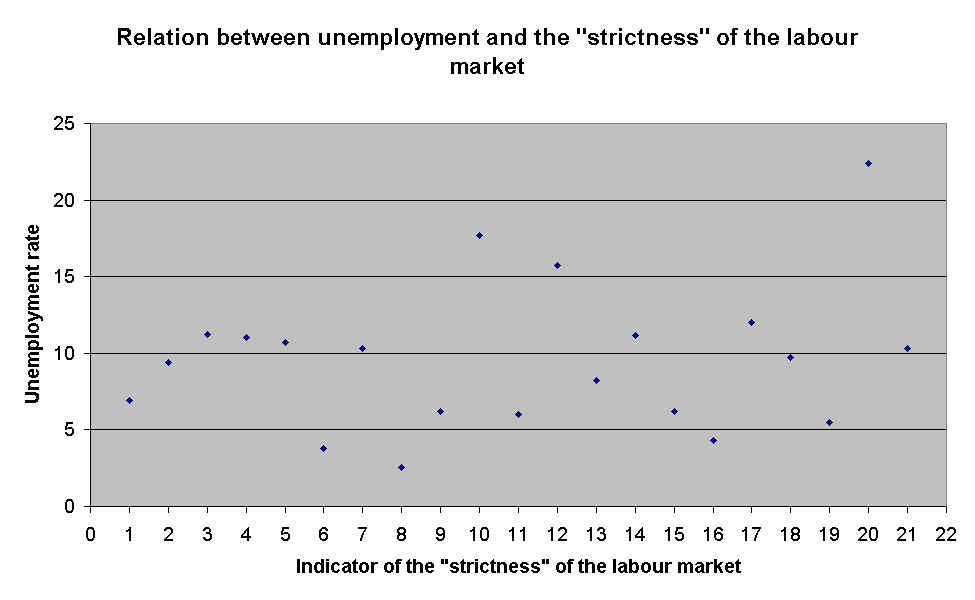

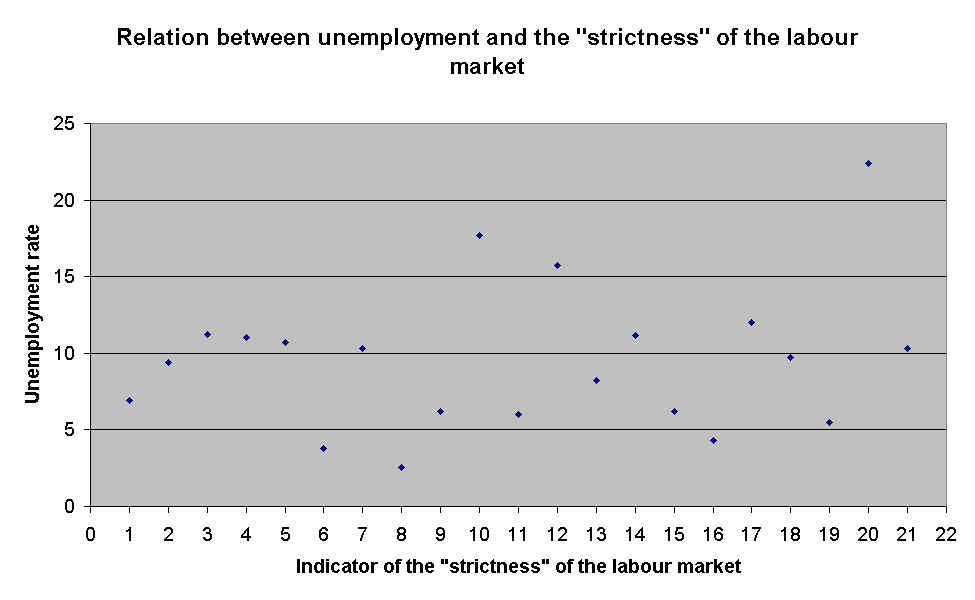

In the following graph the 22 countries are plotted according to their positions within the ranking in table 1 and their rates of unemployment in 1993 (it has to be recalled than the overall indicator of rigidity is based on different indicators on the period 1985-1993). As it can be easily seen, it is impossible to detect a positive correlation between labour market rigidity and unemployment. While it is true that a very flexible country like the US has a quite lower unemployment rate than rigid countries like Spain, it is also true that Canada and Italy - which are at the opposite sides of the rigidity ranking - show quite similar rates of unemployment. In addition, in the middle of the ranking - from the 8th to 13th position - similar degrees of rigidity are combined with unemployment rates which range from 2.54 (Japan) to more than 15 (Finland and Ireland). On the whole, there is no evidence that more rigidities directly imply a higher rate of unemployment. Of course, in the following graph only a static direct relationship is reported. A more reliable exercise should propose a dynamic specification and should control for other causes of unemployment. From this respect, recent research efforts are finalised to the definition of a dynamic indicator of "labour market reform" which should be contrasted with the rate of change of the unemployment rate. The problem here is the availability of reliable and comparable data.

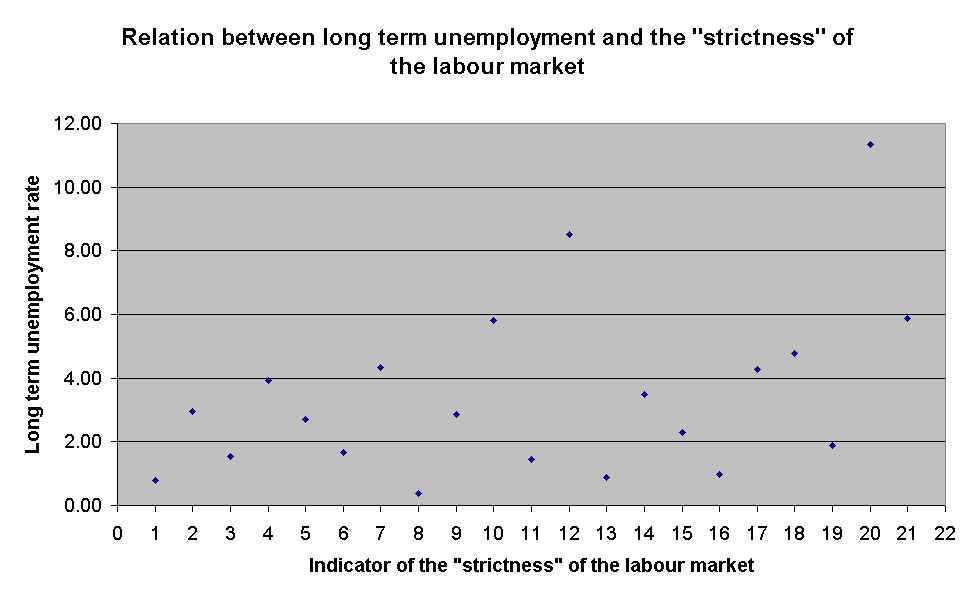

Notwithstanding the lack of any clear correlation between rigidity and the overall official unemployment rate, a different picture emerges when only long-term unemployment is taken into account. As it is shown in the following graph.2, a rough positive correlation between the two indicators can be detected. Also in this case quite different labour markets show very similar long-term unemployment rates (Canada and Portugal; Australia and France; the UK and Greece), yet the plot is less scattered than the one referred to the overall unemployment rate. Thus, one can concludes that labour market rigidities have more adverse consequences on the long-term unemployment rates than on the overall unemployment rates.

While comparisons of different national employment performances are generally based on the official overall unemployment rates, sometimes different indicators may be more properly taken into account. Graph.2 is an example where rigidity is combined with an indicator of "sclerosis" of the labour market. As it has been discussed in Section 1, long-term unemployment is a proper indicator of the social desease which can be associated with a given unemployment rate. From this respect, it is interesting to analyze the level and the incidence of long-term unemployment in different OECD countries.

Table 2: the Composition of Unemployment: Total Unemployment and Long term Unemployment (1975-1996)

Official Unemployment Rate |

Long-Term Unemployment Rate |

Incidence of long-term unemployment on total unemployment |

Official Unemployment Rate |

Long-Term Unemployment Rate |

Incidence of long-term unemployment on total unemployment |

|

1975 |

1983 |

|||||

France |

3,66 |

0,58 |

15,85 |

8,02 |

2,99 |

37,28 |

Germany |

3,95 |

*** |

*** |

7,90 |

2,60 |

32,91 |

Italy |

3,34 |

*** |

*** |

9,42 |

4,84 |

51,38 |

Turkey |

7,20 |

*** |

*** |

7,50 |

*** |

*** |

UK |

3,20 |

*** |

*** |

11,81 |

4,91 |

41,57 |

Canada |

7,16 |

0,18 |

2,51 |

11,93 |

1,14 |

9,56 |

Mexico |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

US |

8,45 |

0,45 |

5,33 |

9,61 |

1,28 |

13,32 |

Japan |

2,05 |

0,26 |

12,68 |

2,67 |

0,29 |

10,86 |

Australia |

4,50 |

*** |

*** |

9,80 |

2,45 |

25,00 |

Official Unemployment Rate |

Long Term Unemployment Rate |

Incidence of long-term unemployment on total unemployment |

Official Unemployment Rate |

Long Term Unemployment Rate |

Incidence of long-term unemployment on total unemployment |

|

1993 |

1995 |

|||||

France |

11,13 |

3,50 |

31,45 |

11,7 |

4,9 |

42,3 |

Germany |

6,20 |

2,29 |

37,00 |

8,2 |

4,0 |

48,3 |

Italy |

10,34 |

5,87 |

56,78 |

11,9 |

7,6 |

63,6 |

Turkey |

7,50 |

3,32 |

44,30 |

6,8 |

2,5 |

36,3 |

UK |

10,32 |

4,32 |

41,90 |

8,8 |

3,8 |

43,6 |

Canada |

11,24 |

1,55 |

13,78 |

9,5 |

1,3 |

14,1 |

Mexico |

3,20 |

*** |

*** |

5,7 |

0,1 |

1,5 |

US |

6,92 |

0,80 |

11,56 |

5,6 |

0,5 |

9,7 |

Japan |

2,54 |

0,36 |

14,29 |

3,1 |

0,6 |

18,2 |

Australia |

11 |

3,92 |

35,64 |

8,6 |

2,6 |

30,8 |

Official Unemployment Rate |

Long Term Unemployment Rate |

Incidence of long-term unemployment on total unemployment |

|

1996 |

|||

France |

12,4 |

4,9 |

39,5 |

Germany |

9,0 |

*** |

*** |

Italy |

12,0 |

7,9 |

65,6 |

Turkey |

5,9 |

2,6 |

43,5 |

UK |

8,2 |

3,3 |

39,8 |

Canada |

9,7 |

1,3 |

13,9 |

Mexico |

*** |

*** |

2,2 |

US |

5,4 |

0,5 |

9,5 |

Japan |

3,4 |

0,7 |

19,9 |

Australia |

8,6 |

2,4 |

28,4 |

|

Sources: OECD, Employment Outlook Long Term Unemployment Rate is defined as the ratio of the number of people having been unemployed for 1 year and over and the total labour force. The incidence of long term unemployment on total unemployment is the ratio between the long term unemployment rate and the official unemployment rate. Notes: In the panel for the year 1975, the data for Canda refer to 1976, and the data for Japan to 1977. |

|||

Over time, the overall employment performance shows a positive trend in the US, the UK and Turkey while a clear deterioration is detectable in continental Europe (Germany, France and Italy) and Japan (althoug this country still shows the lowest unemployment rate). Interestingly enough, countries with the historical and actual worst employment performances show a very high incidence of long-term unemployment (in 1995 equal to 63,6% in Italy, 48,3% in Germany, 42,3% in France). Yet, long-term unemployment also affects the UK, Turkey and Australia which present a decrease in the overall unemployment over the ‘90s. Differently, the more flexible US labour market seems to be characterized by a structurally low incidence of long-term unemployment (nowadays lower than 10%), while Japan exhibits a recent deterioration of the ratio between the long-term and the total unemployment. Given this statistical framework, European labour markets are in a very serious situation not only because of the level of the overall rates of unemployment but also because of the high incidence of the long-term unemployed (potentially embedded in the "unemployment trap", see Section 1).

On the other hand, other statistical considerations suggest to reconsider the overall comparison between European and US employment performances. On the one hand, Europe show higher unemployment rates and - more worrying - a higher incidence of long-term unemployment; on the other hand, the official rate of unemployment does not take into account discouraged workers (people willing to work but not seeking for a job) and especially involuntary part-time (people willing to work full-time, but forced to work part-time). This last category is quite more diffused in the US than in Europe.

In the following table 3, countries are compared accordingly to the official unemployment rate and to the corrected unemployment rate (this combined measure is equal to the officially unemployed+discouraged workers+half of the involuntary part-time workers divided by the labour force; source: OECD, 1995). Unfortuantely, the table refers to 1983 and 1993, while no similar computations have been proposed in more recent years.

As it can be noticed, once additional categories of the labour force are taken into account, in 1993 differences between continental Europe and the US persist, but tend to narrow. Moreover, countries characterized by official rates close to the "natural rate of unemployment" such as Japan, Mexico and - to a lesser extent - the US result with combined measures ranging from 5.7 to 10.2.

Table 3: official and corrected unemployment rates

Official Unemployed as % of Labour Force |

Discouraged Workers as % of Labour Force |

Involuntary Part-time Workers as %of Labour Force |

Corrected Unemployment rate |

|

1983 |

||||

France |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

Germany (1984) |

6,7 |

*** |

0,7 |

*** |

Italy |

8,4 |

1,1 |

1,2 |

10,2 |

Turkey |

7,5 |

*** |

*** |

*** |

UK |

11,2 |

1,3 |

1,5 |

13,2 |

Canada |

12,0 |

1,6 |

3,9 |

15,6 |

Mexico |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

US |

9,8 |

1,5 |

2,9 |

12,7 |

Japan (1984) |

2,7 |

4,5 |

1,2 |

8,0 |

Australia |

9,7 |

1,6 |

3,2 |

12,9 |

1993 |

||||

France |

11,4 |

0,2 |

4,8 |

14,0 |

Germany |

7,7 |

*** |

1,5 |

*** |

Italy (1991) |

10,2 |

2,6 |

2,3 |

13,6 |

Turkey |

8,1 |

0,4 |

0,1 |

8,5 |

UK |

10,3 |

0,6 |

3,2 |

12,5 |

Canada |

11,3 |

0,9 |

5,5 |

14,8 |

Mexico |

2,6 |

1,3 |

5,2 |

6,4 |

US |

6,9 |

0,9 |

5,0 |

10,2 |

Japan |

2,6 |

2,2 |

1,9 |

5,7 |

Australia |

10,8 |

1,6 |

6,9 |

15,6 |

Note: The data mostly refers to the active population (ages 15-64) only.In the calculations of the percentages of discouraged workers, labour force includes discouraged workers.

Corrected unemployment rate counts the unemployed plus discouraged workers and half of involuntarily employed workers as a percentage of the labour force (employed and officially unemployed).

Source: OECD, Employment Outlook

Data reported in the last two tables suggest to be very cautious in comparing different national labour markets. Indeeed, the rough comparison between officially unemployment rates can only be the starting point of the analysis: more sophisticated indicators should take into account discouraged workers, involuntary part-time and the internal composition of the unemployment pool, with particular attention to the most worrying aspect of the long-term unemployment.

References

* As it is clear from the sections above, mainstream labour economics is nowadays focused on labour market rigidities and on the reform proposal for achieving more flexible labour market institutions in continental Europe. A very useful , complete and non-technical guide to the dominant interpretation of current levels of unemployment can be found in:

Centre for Economic Policy Research, 1995, European Unemployment: Is there a Solution?, London., CEPR.

* More technical contributions about the impact of higher hiring and firing costs can be found in:

Lazear, 1990, Job Security Provisions and Unemployment, Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol.105, 699-726.

Bertola, 1990, Job Security, Employment, and Wages, European Economic Review, vol. 34, 851-86.

Bentolila, S. - Bertola, G., 1990, Firing Costs and Labour Demand: How Bad is Eurosclerosis?, Review of Economic Studies, vol.57, n.3, 381-402.

* A useful summary of the mainstream position about the relationship between unemployment, wages and the labour market is the introduction to:

Layard, R. - Nickell, S. - Jackman, R. 1991. Unemployment: Macroeconomic Performance and the Labour Market, Oxford, Oxford University Press

* A less technical version of the previous book, where mainstream policy implications are fully clarified is:

Layard, R. - Nickell, S. - Jackman, R. 1994. The Unemployment Crisis, Oxford, Oxford University Press

* Finally, an extreme orthodox and pedagogical point of view in comparing American and British labour market can be appreciated in:

Pencavel, J. (1994), British Unemployment: Letter from America, Economic Journal, vol.104, 621-32.

* Some theoretical articulations of mainstream labour economics are the following contributions, dealing with hysteresis, long-term unemployment and unemployment trap.

Blanchard, O. - Summers, L.H. 1987. Hysteresis in Unemployment, European Economic Review, vol.31, 288-95

Blanchard, O. - Summers, L.H., 1986; Hysteresis and the European Unemployment Problem, NBER Macroeconomics Annual, vol.1, 15-78.

Cross, R.B.,1987, Unemployment, Hysteresis and the Natural Rate Hypothesis, Oxford, Blackwell.

Graafland, J:J., 1991, On the Causes of Hysteresis in Long-term Unemployment in the Netherlands, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, vol.53, 155-170.

Jackman, R. - Layard, R, 1991, Does Long-term Unemployment Reduce a Person’s Chance of a Job? A Time-series Test, Economica, vol.58, 93-106.

* The following works put forward proposals of new institutional settings addressed to create the conditions for more flexible labour markets. In particular, the OECD Job Study has been very influential in shaping labour policies all around the Western world, although national and international union organizations have fully expressed their deep disapproval for the unilateral approach which has been assumed in that report. Among the ten prescriptions which can be found in the Job Study and following OECD publications one regards wage moderation and three concerns labour market flexibility (reduction of unemployment benefits, deregulation of recruitments and dismissals, higher degrees of freedom in unusual working hours, temporary contracts and part-time).

OECD,1994a, OECD Jobs Study. Facts, Analysis and Strategies, Paris, OECD

OECD, 1994b, Employment Outlook, Paris, OECD.

OECD, 1995, Employment Outlook, Paris, OECD

* The following contributions are more theoretical and deal with employment protection (Emerson and Piore), unemployment benefits (Snower) and the difficulty of a transition towards a more flexible labour market (Bertola-Ichino). In Pacelli-Rapiti-Revelli one can find an accurate empirical analysis which demonstrates - once that small firms are taken into account - that Italian labour market is far less rigid than what is commonly assumed.

Emerson, M., 1988, Regulation or Deregulation of the Labour Market, European Economic Review, vol.32, 775-817.

Piore, M., 1986, Perspectives on Labor Market Flexibility, Industrial Relations, vol.2, 146-88.

Bertola,G. and Ichino, A. 1995. Crossing the River. A Comparative Perspective on Italian Employment Dynamics, Economic Policy, no. 21, 359-420

Pacelli, L. - Rapiti, F. - Revelli, R.., 1995, Intensity of Innovation, Employment and Mobility of Workers in Italy: Evidence from a Panel of Workers and Firms, paper presented at the conference: The Effects of Technology and Innovation on Firm Performance and Employment, Washington, National Academy of Science, May 1-2.

Snower, D., 1994, Converting Unemployment Benefits into Employment Subsidies, American Economic Review, vol. 84, 65-70.

Snower, D., 1995, Unemployment Benefits: An Assessment of Proposals for Reform, International Labour Review, vol.134, 625-47.

* The Spanish case is a paradigmatic example of deregulation and so it has been carefully studied:

Bentolila, S. - Dolado, J., 1994, Labour Flexibility and Wages: Lessons from Spain, Economic Policy, n.18, 53-100.

Bentolila, S. - Saint-Paul, G., 1992 , The Macroeconomic Impact of Flexible Labour Contracts with an Application to Spain, European Economic Review, vol.36, 1013-47.

Toharia, L., 1997, The Labour Market in Spain, mimeo.

* Although income distribution is out of the scope of the present analysis, it has been noticed that the least regulated labour markets in the Western developed world - the US and the UK - exhibit the sharpest level and the larger increase in income differentials. The following readings can be a useful introduction to the subject and they also provide a comparison between a relative rigid labour market (Germany) and a flexible one (the US).

Gittleman, M. - Joyce, M., 1995 , Earnings Mobility in the United States, 1967-91, Monthly Labor Review, vol.118, n.9, 3-13.

Gittleman, M. -Joyce, M., 1996; Earnings Mobility and Long-run Inequality: An Analysis Using Matched CPS Data, Industrial Relations, vol.35, 180-96.

Gregg, P. - Machin, S., 1994, Is the UK Rise in Inequality Different?, R. Barrell (ed.), The UK Labour Market: Comparative Aspects and Institutional Developments, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Burkhauser, R.V. - Poupore, J.G., 1993, A Cross-National Comparison of Permanent Inequality in the United States and Germany, Cross-National Studies in Aging Program Project Paper, n.10, Syracuse University, december.

Burkhauser, R.V. - Holtz,-Eakin, D. - Rhody, S.E., 1997, Labor Earnings Mobility and Inequality in the Unites States and Germany during the Growth Years of the 1980s, NBER Working Paper Series, n. 5988.