Unemployment, Structural Change and Globalization

M. Pianta and M. Vivarelli

UNEMPLOYMENT AND WAGES

by M. Vivarelli

Conventional economic wisdom deals with the labour-market in a way that it is common to any other commodity: within the labour market a proper labour price (wage) has to equalise the demand for labour with the labour supply. As in any other market, the occurrence of disequilibrium - which in this case means unemployment - can be avoided by price (wage) flexibility which can always clear the market. In this framework, unemployment is always voluntary, since it depends on the wage viscosity: workers and unions do not accept a wage decrease and so unemployment persists.

The labour economics generally assumes the point of view briefly summarised above; this point of view is short-term (the wage adjustment should assure the achievement of the equilibrium immediately, if there are not hindering factors) and belongs to the so-called "partial equilibrium analysis" (attention is focused only on the labour market and possible counter-effects and influences in other markets, such as the good and capital markets, are not taken into account). This short-term approach will be critically discussed in Section 2.

Yet, mainstream economics also puts forward an inverse relationship between employment and wages in the long-run. In this case, the hypothesis is that higher wages induce a capital-labour substitution and so can involve an increase in the structural (technological) unemployment (for a different approach to technological unemployment, see "Unemployment and Technical Change"). This long-term approach will be critically discussed in Section 3.

2. Employment and wages in the short-term.

Most of labour economists look at unemployment as a short-term disequilibrium which can be solved within the labour market, generally through an adjustment of the price of labour: the real wage (see, for instance, Layard-Nickell-Jackman, 1991 and 1994; for "internal" critiques of this point of view, see Phelps, 1992 and Freeman, 1995). The main methodological options of this approach are the short-term perspective and the choice of a partial equilibrium analysis.

As far as the first option is concerned, unemployment is seen as a temporary deviation from the steady-state equilibrium, which in the long-run can be reached again. Two main causes can induce unemployment: either the real wages, which are higher than the equilibrium ones (this is the so-called "classical unemployment"), or the "effective demand", which is lower than the equilibrium one (this is the so-called "Keynesian unemployment"). While in the eighties - especially in interpreting British unemployment - the second position was dominant (see Layard-Nickell- Bean, 1986; Pissarides, 1986; Coen-Hickman, 1988) - nowadays, the first position has gained the favour of the majority of labour economists, especially in dealing with the so-called "Eurosclerosis" (this should be due either to rigidities in the labour market - see Dreze-Bean, 1990 - or to lack of credibility in the shift to more flexible labour market institutions, see Bertola-Ichino, 1995; for a critique, see Malinvaud, 1990 and 1994; see also Unemployment and the Labour Market).

Both classical and Keynesian unemployment can be solved through price or wage adjustments and persistent unemployment can be explained as a consequence of wage or price rigidities. Theoretically, persistent unemployment should in turn weaken the workers and unions bargaining power and so induce a decrease in wages. In this view wages and unemployment are inversely correlated (Phillips curve) and the labour market should be a self-adjusting institution. Yet, many countries - especially the European ones - exhibit a tendency to persistent high rates of unemployment. According to mainstream economics, this persistence is due to some viscosity which hinders the correct running of the self-adjustment mechanism. In other words, economists suggest that unemployment can persist and often translate into long-term unemployment only if it does not exert a proper downward pressure on real wages.

For example, wage rigidities can be explained by the so-called "insider-outsider theories" (see Lindbeck-Snower, 1986, 1987 and 1988). According to this theory, within the labour force one can distinguish the incumbent workers (the insiders) from the unemployed (the outsiders). The insiders enjoy a rent due to labour turnover costs, such as firing costs, hiring costs, selection procedures, training courses, motivation to team work and so on (see Centre for Economic Policy Research, 1995, chap.3). If insiders can rely on this short-term cost-gap, current wages become partially independent of the rate of unemployment and almost totally independent of the rate of long-term unemployment, since hiring long-term unemployed workers requires higher training costs (see Layard-Nickell, 1986; Layard-Bean, 1989).

Other theories assume a different approach and they point out that wages higher than the equilibrium level can be explained within the borders of the optimization behaviour of firms. The starting point is that labour is not and homogeneous commodity: workers can differ in their abilities and skills and their productivity can vary depending on the amount of effort that they devote to their tasks. Since the direct monitor of the effort is difficult and costly, higher productivity can be incentivated by higher wages (the so called "efficiency wages", see Solow, 1979; Shapiro-Stiglitz, 1984; Greenwald-Stiglitz, 1993). According to this view, wages may be sticky because it is costly for firms to cut them.

Finally, wages can be rigid as a result of an "implicit contract" between the firm and the workers: if the latter are risk averse, they might prefer to gain a stable rigid wage than to receive a floating wages according to the different status of either the economic cycle or the firm’s profitability (see Rosen, 1985)

Whatever reason can justify wage rigidity, according to the partial equilibrium analysis, sticky wages hinder the labour market adjustment and they must be removed in order to deal with the unemployment problem. In fact, the policy implications of these analyses are straightforward: what is necessary is price and especially wage flexibility, since the rigidity of the cost of labour is seen as the main cause of high and persistent unemployment (this viewpoint is commonly assumed in discussing European unemployment in comparison with the better situation of U.S. labour market (see OECD, 1994). Together with wage flexibility, a move towards a higher sectorial and geographical mobility is often claimed as a necessary institutional change in labour market dynamics (see Unemployment and the Labour Market).

Yet, if we move from a short-term and partial equilibrium framework to a more open and general approach, some counter-effects of wage moderation can be singled out.

Indeed, the partial equilibrium analysis does not allow to take into account those determinants of unemployment which can be detected out of the labour market (such as lack of aggregate demand, technical change, capital shortage, financial rationing; see Unemployment and Aggregate Demand and Unemployment and Technical Change). If unemployment is not only related to higher wages, but also to other determinants, employment policy must be much more multifaceted than being a simple call for wage moderation.

While the critique above can be considered external, there is also an internal critique to the conventional approach put forward by labour economists. In fact, while this stream of literature explicitly considers the inflationary effects of wage increases (throughout a mark-up mechanism, see Layard-Nickell-Jackman, 1991), the recessionary effect of wage decreases (throughout the decrease in the purchasing power and so in the effective demand) is never taken into account. Indeed, the following critique by Malinvaud is still illuminating; talking about the concept of the demand for labour (inversely correlated with real wages), the French economist puts forward the following opinion:"...Such a redefinition reacts on the shape of the curve, since an increase in the real wage rate leads to an increase in the aggregate demand for goods, hence to an increase also in the demand for labour by enterprises. This phenomenon runs counter to the supposed down-ward orientation of the curve; one must then account for it when the aggregate relationship is specified." (Malinvaud, 1994, p.83).

3. Employment and wages in the long-term

While in the short-term the alleged inverse correlation between wages and employment is mediated by the demand for labour, a similar relationship in the long-run is due to technological choices, and particularly to the possibility to substitute labour with capital.

There is a widespread opinion that at least a portion of current unemployment in the industrialized and newly industrialized countries can be seen as the effect of labour-saving technologies which have been introduced at an accelerating rate since the mid ‘70s (see Unemployment and Technical Change). The conventional economic wisdom again proposes a decrease in wages as a suitable solution (the other side of the coin is to explain the labour-saving bias of current technologies as a consequence induced by an upward tendency in wage dynamics during the ‘70s). The argument is based on the "isoquant" theory which associates a given level of output to an infinite number of technological available combinations of labour and capital: according to this view, a change in the relative price of productive factors (capital and labour) induces a technological substitution in favour of the factor which has become cheaper.

Erroneously attributed to Hicks (1932), the induced bias approach was actually proposed by Knut Wicksell: "For as soon as a number of labourers have been made superfluous by these changes, and wages have accordingly fallen, then, as Ricardo failed to see, the old methods of production....will become more profitable; they will develop, using labour more intensively and absorb the surplus of idle labourers" (Wicksell, 1961, p.137). In other words, as wage flexibility assures the labour market equilibrium in the short-term, wage moderation can induce a reverse towards labour-intensive techniques in the long-run. Other authors tried to extend this argument to the macroeconomic dynamics (Kennedy, 1964; Von Weizacker, 1966; Malinvaud, 1982).

Different critiques can be opposed to this kind of approach.

Starting from microeconomics, given a shock in one particular factor cost, an entrepreneur will actually try to reduce any cost without paying particular attention to saving the more expensive factor (Salter, 1966). According to this view, profit maximizing firms will try to save money wherever they can and according to the relative negotiating powers of the involved parties. For instance, in the ‘70s and ‘80s European entrepreneurs associations have asked for wage moderation while the highest rates of increase in relative costs have come from oil and raw materials in the ‘70s and from the financial system in the ‘80s.

Turning the attention to macroeconomic trends, it has been found that, at least in some historical periods, technological innovation is much more driven by market forces such as aggregate demand than by the relative costs of production factors (see Schmookler, 1966; Scherer, 1982).

At any rate, there is a more fundamental critique which has to do with the intrinsic nature of technical change. According to Rosenberg (1976 and 1982), technology is not a putty good that can be used in different ways and at different times according to market signals. In other words, the relationship between technology and market forces cannot be reduced to a "one way" interaction: "Although economic forces and motives have inevitably played a major role in shaping the direction of scientific progress, they have not acted within a vacuum, but within the changing limits and constraints of a body of scientific knowledge growing at uneven rates among its component sub-disciplines." (Rosenberg, 1976, p.270).

According to Dosi (1982 and 1988), after a radical technological revolution, which involves a change in the "technological paradigm", technical change develops through a so-called "technological trajectory". A technological trajectory is a cumulative and irreversible process which has its origins inside the paradigm while its development follows a continuous and constrained path ("normal" technical progress). Along a trajectory - such as the current diffusion of the Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) - incremental innovations are dominant over radical innovations and technical change is bounded by the tradeoffs posed by the nature of the current paradigm; institutions and market forces do not cease to have an important, selective role, yet every signal from the market is filtered by actual technological opportunities and compared with actual technological capabilities.

In this framework, the induced bias approach appears oversimplified and unacceptable. Even if we assume that high and permanent wage increases can induce the selection of a technological paradigm which is characterized by a labour-saving bias, once the labour-saving technological trajectory is well-established, it is impossible to come back to a more labour-intensive path just by changing or canceling the original market signal.

Indeed, technology has its own rules dictated by scientific linkages and economic forces have to deal with these technological boundaries. Moreover, when firms decide their investments and their R&D strategies, they have to consider learning opportunities and the important role of consolidated routines inside the firms. Taking into account what has been learned about the current technology, the improvements which may be reached in keeping to use the same technology and the costs associated with a shift to a new technologies, the set of technological choices is likely to be bounded and relatively unresponsive to market signals (this is what has been called "localized technological progress", see Stiglitz, 1987). If firms are often embedded in the current technology, the dynamic maximization of future flows of discounted profits often leads to confirm the present combination of productive factors (even if static maximization would have involved factor substitution). If this is the "micro" behaviour of firms, at the aggregate it will be found a strong "path dependency" in the technological development of a given economic system (see David, 1975).

Going back to the relationship between wages and the use of labour, if the nature of technology and the importance of learning are properly taken into account the following conclusion by Christopher Freeman seems to be quite realistic: "An important conclusion follows from this overall assessment of "induced innovation". It is, that there is inherent plausibility in the Hicks inducement theory, biasing the long term direction of technical change in a labour-saving direction. Attempts to generate a reversal of this trend by temporary small reductions in the relative price of labour are extremely unlikely to be effective" (Freeman-Soete, 1987, p.46).

In neo-classical terms, the contemporaneous studies on the nature of technological progress and on the relationship between economics and technology show that the marginal rate of substitution between capital and labour can be close to zero because of localized technological progress driven by long-term maximizing agents fully aware of the role of internal routines and learning opportunities. In this more realistic framework, cumulativeness and irreversibility of technological progress rule out the possibility of a reverse in techniques induced by decreasing wages.

On the whole, while a static, short-term and partial equilibrium analysis leads to state a clear inverse relationship between wages and employment, more open, dynamic and general approaches cast many doubts on the possibility to use wage moderation as an instrument of employment policy both in the short and in the long-term.

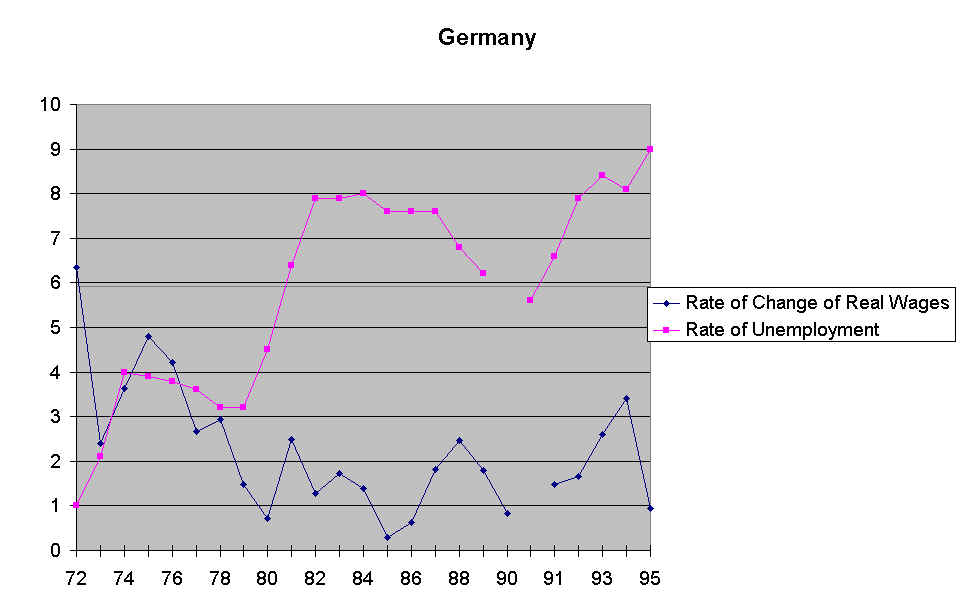

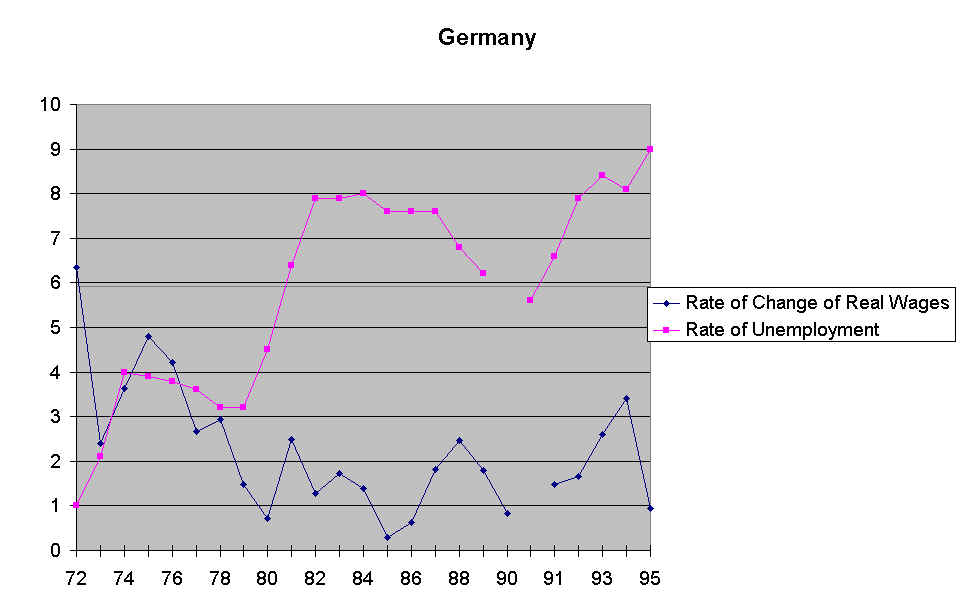

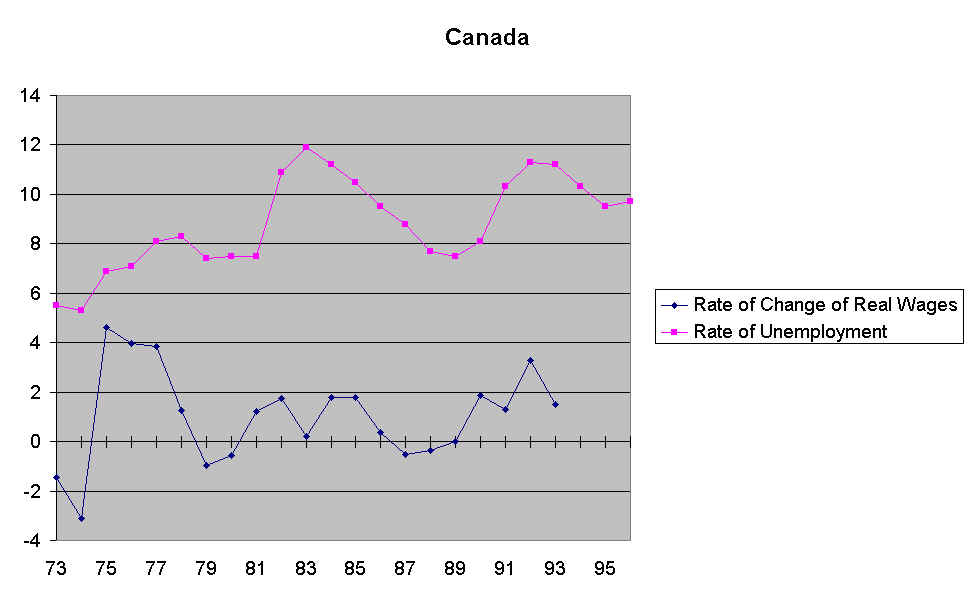

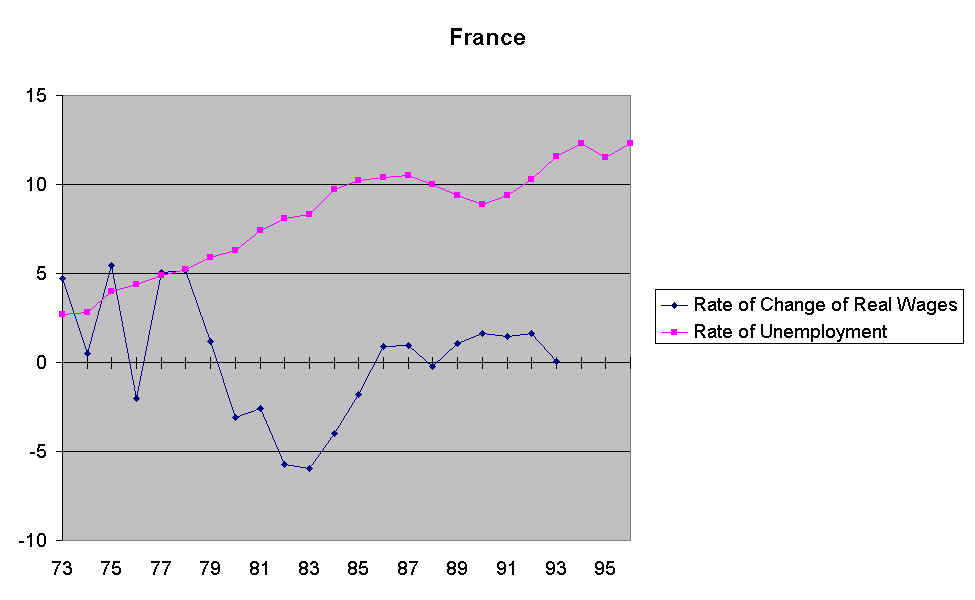

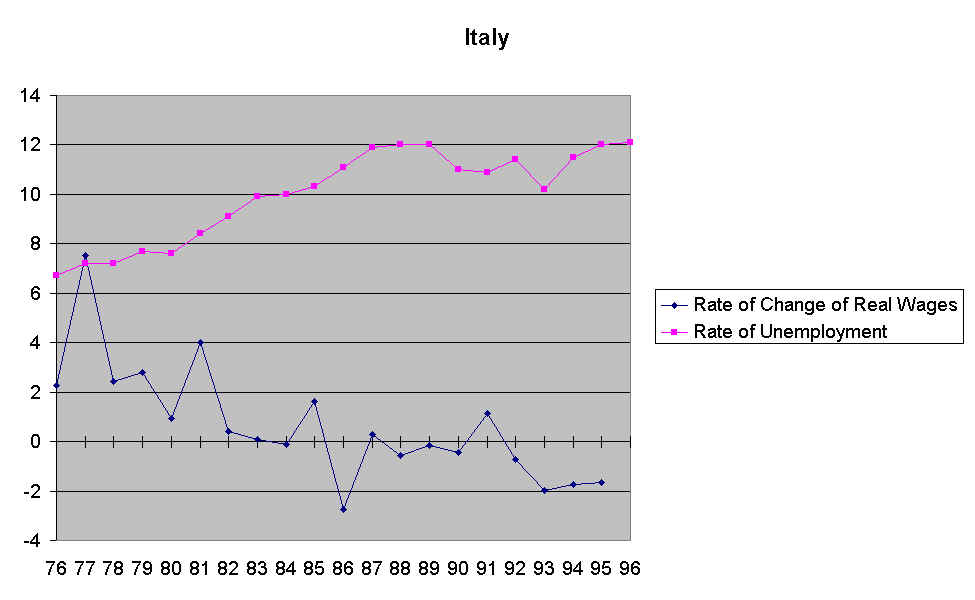

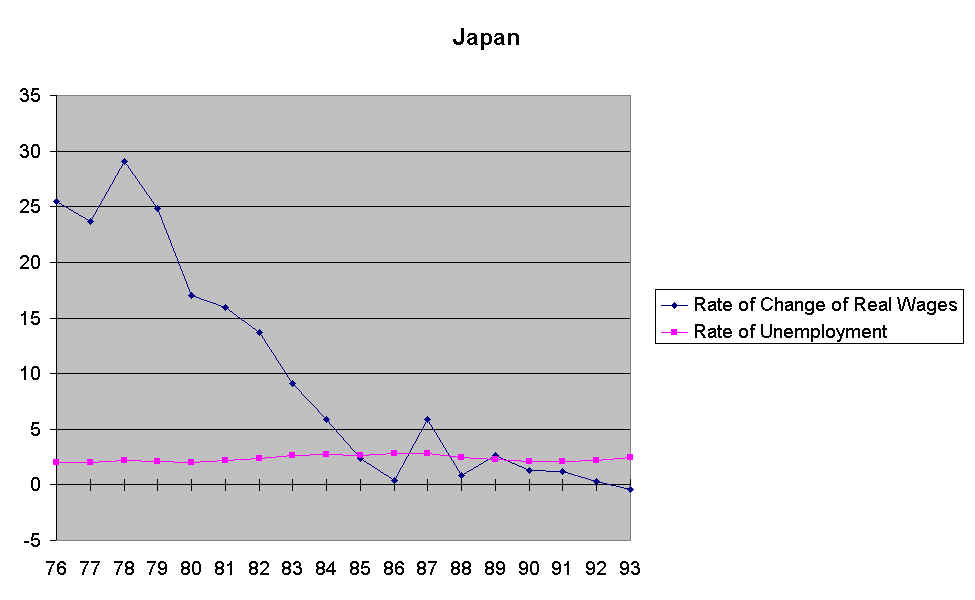

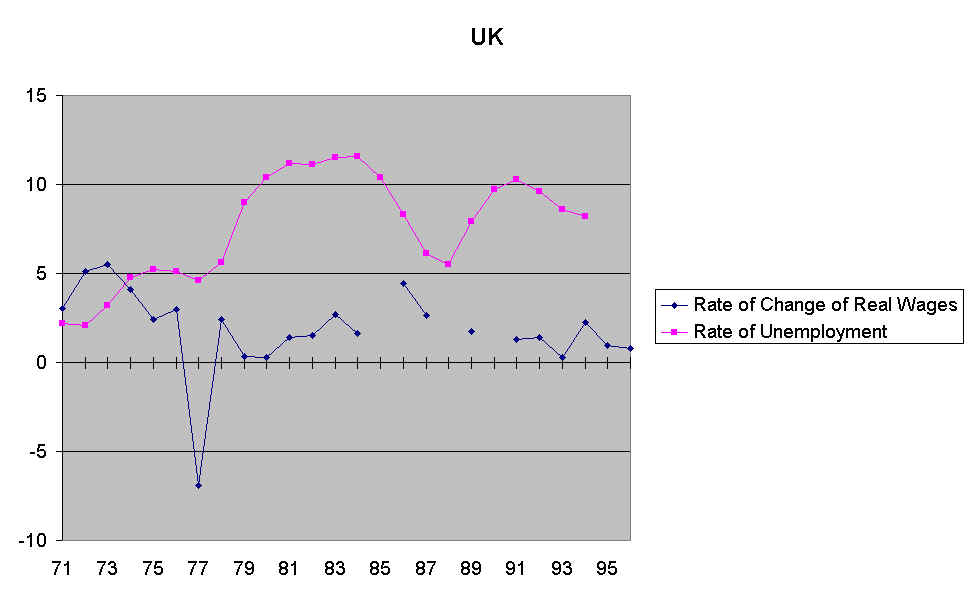

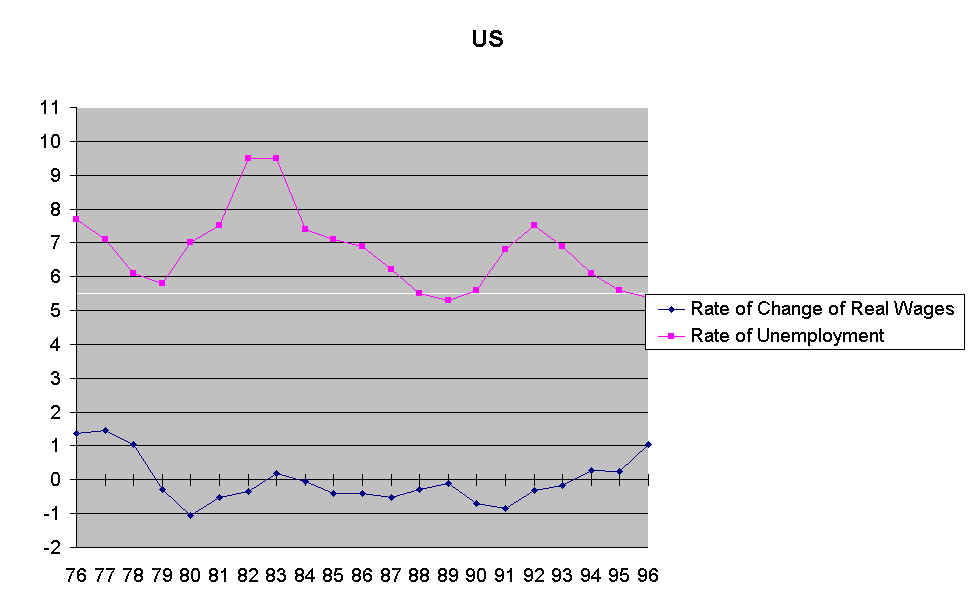

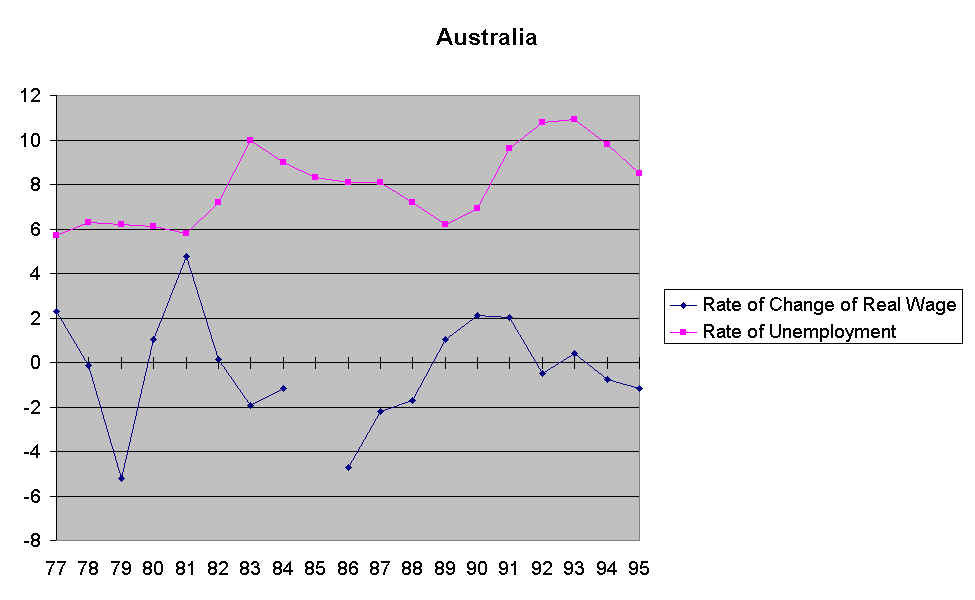

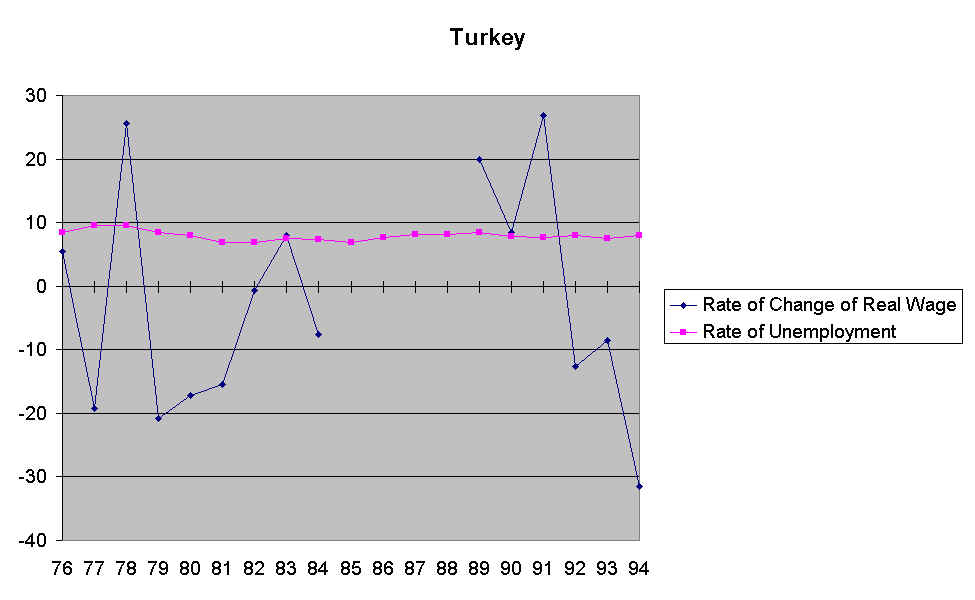

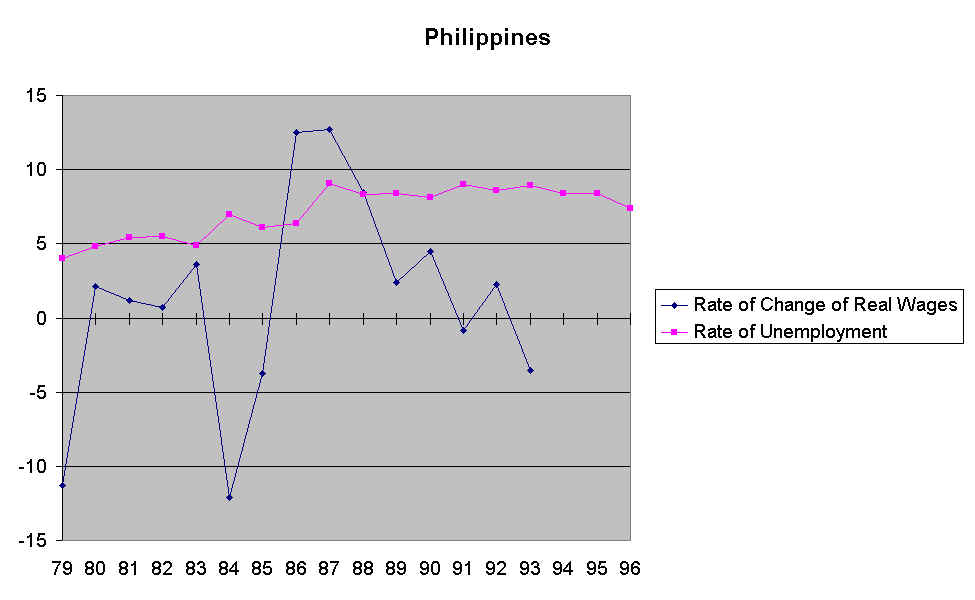

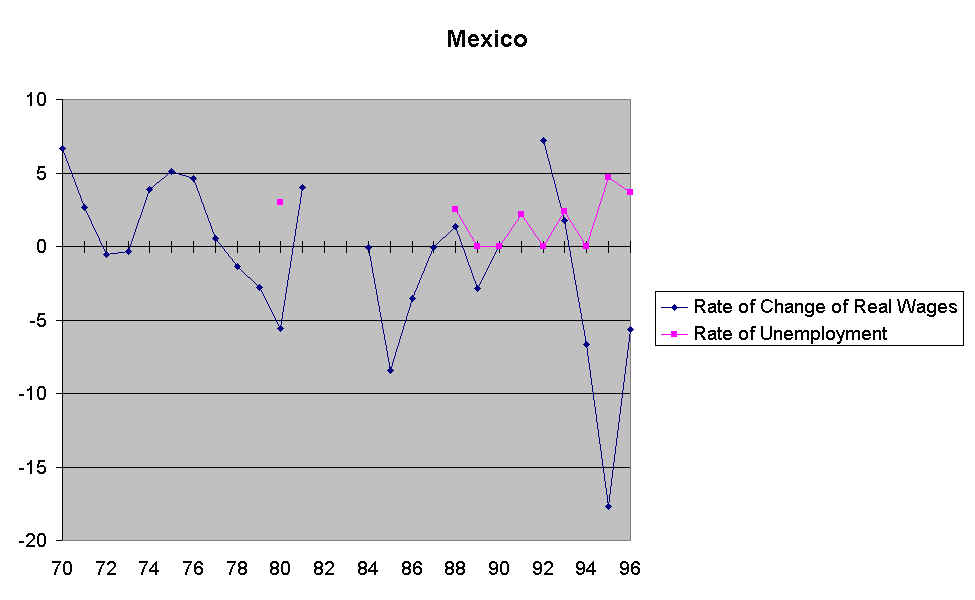

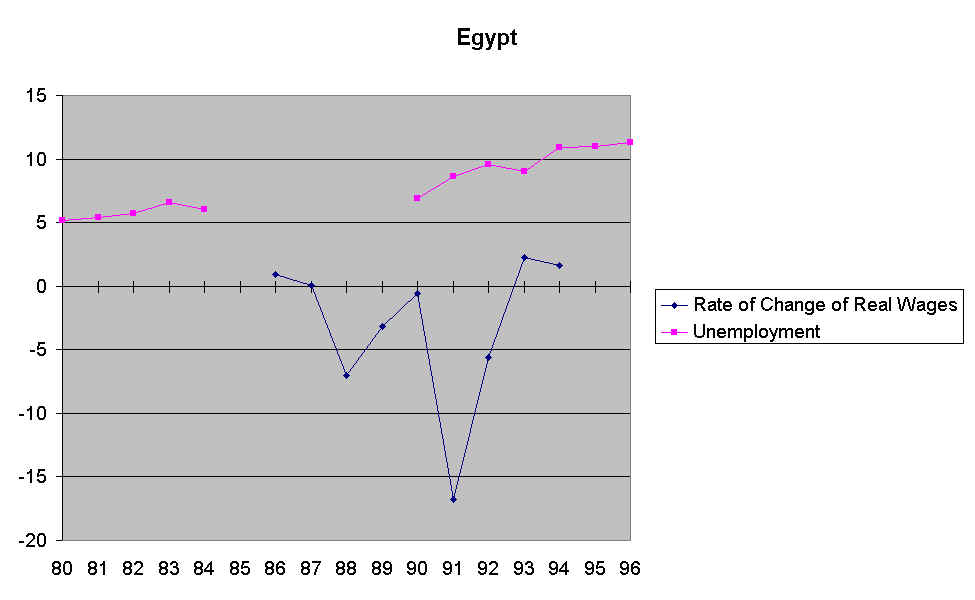

In the following plots some empirical evidence regarding 12 industrialised and newly industrialised countries are reported. In particular, yearly rates of change in real wages and unemployment rates during the last two decades are presented (breaks are the consequence of missing data while in the case of Germany indicate the shift to data referring to unified Germany).

A common feature coming out from the 12 graphs is that no direct positive (lagged) relationship between change in real wages and unemployment can be detected in any of the 12 countries (see discussion above). Of course, the evidence here presented is a very rough one to one correspondence; yet, it seems sufficient to exclude that unemployment can be ruled out only and simply by wage moderation.

Starting from the USA (a very unregulated labour market, see also Unemployment and the Labour Market) , while a positive relationship between the two series is detectable till the mid ‘80s, no clear correspondence emerges in the subsequent years; in particular, wage moderation does not seem to have avoided an increase in unemployment during the recession of the early ‘90s.

While in Canada the possibility of an impact of wages onto unemployment rates cannot be excluded, in Australia the two patterns are quite independent and a negative link seems to emerge in recent years.

In the four largest European countries, a common trend from higher wage increases in the ‘70s to wage moderation in the ‘80s and ‘90s can be seen. Yet, unemployment was around 5% in the ‘70s and it is now generally higher than 10%. Among the four countries, only the UK shows an upper turning point and a reverse in the unemployment trend (some supporters of conventional economic wisdom see this as an effect of wage moderation and deregulation of the British labour market, see also Unemployment and the Labour Market). Yet, both France and Italy have experimented a long period of wage moderation - with an overall decrease in real wages during the last 10 years - without getting any result in terms of unemployment rate.

Japan is a peculiar case, characterised by a quasi-full employment situation and by dramatic increases in real wages in the ‘70s and early ‘80s. So, the recent trend towards wage moderation does not turn out as a pre-condition to full employment (at the contrary, it is in these years that Japan has started to suffer some employment problems, especially for aged people).

Turning the attention to newly industrialised countries, data on real wages are much more volatile, because of lagged adjustments to inflation and both the series present missed values. At any rate, in Turkey fluctuating real wages are accompanied by a relative stable (high) unemployment rate; in Egypt wage moderation in the early ‘90 has not avoided an obvious increase in the unemployment rate; in the Philippines decreasing real wages since 1987 has not affected a rate of unemployment close to 10% and finally in Mexico a sharp collapse in real wages in recent years (probably due to the financial crisis) does not seem to have affected the local level of unemployment.

* As far as the short-term negative relation between wages and employment, mainstream economics can exhibit a huge number of models. Notwithstanding the large variety of complementary hypotheses about firms and unions’ behaviours, the degree of market competition, the role of the institutions and so on, a central feature of these models is the focus on the demand for labour. Once neglected the role of the aggregate demand and the possible alternative explanations of unemployment trends, it follows almost automatically that higher wages imply a higher level of unemployment. Moderately critical point of views can be found in the works by Freeman, Malinvaud and Phelps.

Bertola,G. and Ichino, A. 1995. Crossing the River. A Comparative Perspective on Italian Employment Dynamics, Economic Policy, no21, 359-420

Centre for Economic Policy Research 1995. European Unemployment: Is There a Solution?, London, CEPR

Coen, R.M. and Hickman, B.G. 1988. Is European Unemployment Classical or Keynesian?, American Economic Review, vol.78, 188-93

DrŠ ze, J.H and Bean, C.R. (eds.). 1990. Europe’s Unemployment Problem, Cambridge (Mass.) MIT press

Freeman, R. 1995. The Limits of Wage Flexibility to Curing Unemployment, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, vol. 11, 63-72

Layard, R and Bean C. 1989. Why does Unemployment Persist? Scandinavian Journal of Economics, vol.91, 371-96

Layard, R and Nickell, S. 1986. Unemployment in Britain, Economica, vol.53, Supplement, 121-69

Layard, R - Nickell, S. - Bean, C.R. 1986. The Rise in Unemployment: A Multi-country Study, Economica, vol. 53, suppl., 1-22

Layard, R. - Nickell, S. - Jackman, R. 1991. Unemployment: Macroeconomic Performance and the Labour Market, Oxford, Oxford University Press

Layard, R. - Nickell, S. - Jackman, R. 1994. The Unemployment Crisis, Oxford, Oxford University Press

Malinvaud, E. 1990. What Do we Mean by Explaining High Unemployment?, Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, vol.1, 15-26.

Malinvaud, E. 1994. Diagnosis Unemployment, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

OECD 1994. OECD Job Study. Facts, Analysis and Strategies, Paris, OECD

Phelps, E. 1992. A Review of Unemployment, Journal of Economic Literature, vol.30, 1476-90

Pissarides, C. 1986. Unemployment and Vacancies in Britain, Economic Policy, vol. 3, 499-559

* If wage rigidities are at the origin of disequilibrium within the labour market, economic theory has to explain wage stickiness: efficiency wages (Solow and Stiglitz), insider-outsider approach (Lindbeck and Snower) and the implicit contract framework (Rosen) are alternative theoretical explanations of wage viscosity.

Greenwald, B. and Stiglitz, J. 1993. New and Old Keynesian, Journal of Economic Perspective, vol. 7, 23-44

Lindbeck, A. and Snower, D.J. 1986, Wage Setting, Unemployment and Insider-outsider Relations, American Economic Review, papers and proceedings, vol.76, 235-39.

Lindbeck, A. and Snower, D.J. 1987, Efficiency Wages versus Insider and Outsiders, European Economic Review, vol. 31, pp. 407-16.

Lindbeck, A. and Snower, D.J. 1988. The Insider-Outsider Theory of Employment and Unemployment, Cambridge (Mass.), MIT Press

Rosen, S. 1985. Implicit Contracts: A Survey, Journal of Economic Literature, vol. 23, 1144-75.

Shapiro, C. and Stiglitz, J. 1984. Equilibrium Unemployment as a Discipline Device, American Economic Review, vol. 74, 433-44

Solow, R. 1979. Another Possible Source of Wage Stickiness, Journal of Macroeconomics, vol. 1, 79-82.

* As far as the long-term inverse relationship between wages and the use of labour, mainstream economics has proposed the so-called induced bias approach. Critiques to this approach can be found in Salter (firms respond to a particular cost increase by saving on all production costs), Schmookler and Scherer (innovation is driven by aggregate demand and not by factor prices) and Malinvaud (a decrease in wages can induce a labour-saving trajectory but has to be huge and permanent and so it collides with other equilibrium conditions, such as a given level of aggregate demand for consumption goods).

Hicks, J.R. 1932. The Theory of Wages, London, Macmillan

Kennedy, C. 1964, Induced Bias in Innovation and the Theory of Distribution, Economic Journal, vol. 74, 541-47

Malinvaud, E. 1982, Wages and Unemployment, Economic Journal, vol.92, 1-12.

Salter, W. 1966. Productivity and Technical Change, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Scherer, F. 1982, Demand Pull and Technological Invention: Schmookler Revisited, Journal of Industrial Economics, vol.30, 225-37

Schmookler, J. 1966, Invention and Economic Growth, Cambridge (Mass.), Harvard University Press

Weizsacker, Von, C. 1966, Tentative Notes on a Two-sector Model with Induced Technical Progress, Review of Economic Studies, vol.33, 245-51

Wicksell, K. 1961. Lectures on Political Economy, London, Routledge & Kegan, first edn 1901-1906

* The main critique to the induced bias approach has to be based on contemporaneous economic analysis of technical change. Technical progress is generally path-dependent (David and Rosenberg) and localized (Dosi, Freeman-Soete, Stiglitz). If such is the case, the degree of responsiveness to market signals and the degree of technical substitution between capital and labour can both be very low.

David, P. 1975. Technical Choice, Innovation and Economic Growth, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Dosi, G. 1982. Technological Paradigms and Technological Trajectories, Research Policy, vol.11, 147-63

Dosi, G. 1988. Source, Procedure and Microeconomic Effects of Innovation, Journal of Economic Literature, vol.26, 1120- 71

Freeman, C. and Soete, L. (eds) 1987. Technical Change and Full Employment, Oxford, Basil Blackwell

Rosenberg, N. 1976. Perspectives on Technology, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Rosenberg, N. 1982, Inside the Black Box: Technology and Economics, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Stiglitz, J.E. 1987. Learning to Learn, Localized Learning and

Technological Progress, in Dasgupta, P. - Stoneman, P. (eds), Technology Policy and

Economic Performance, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press