International

Labour Organization

Your

health and safety at work

Your

health and safety at work

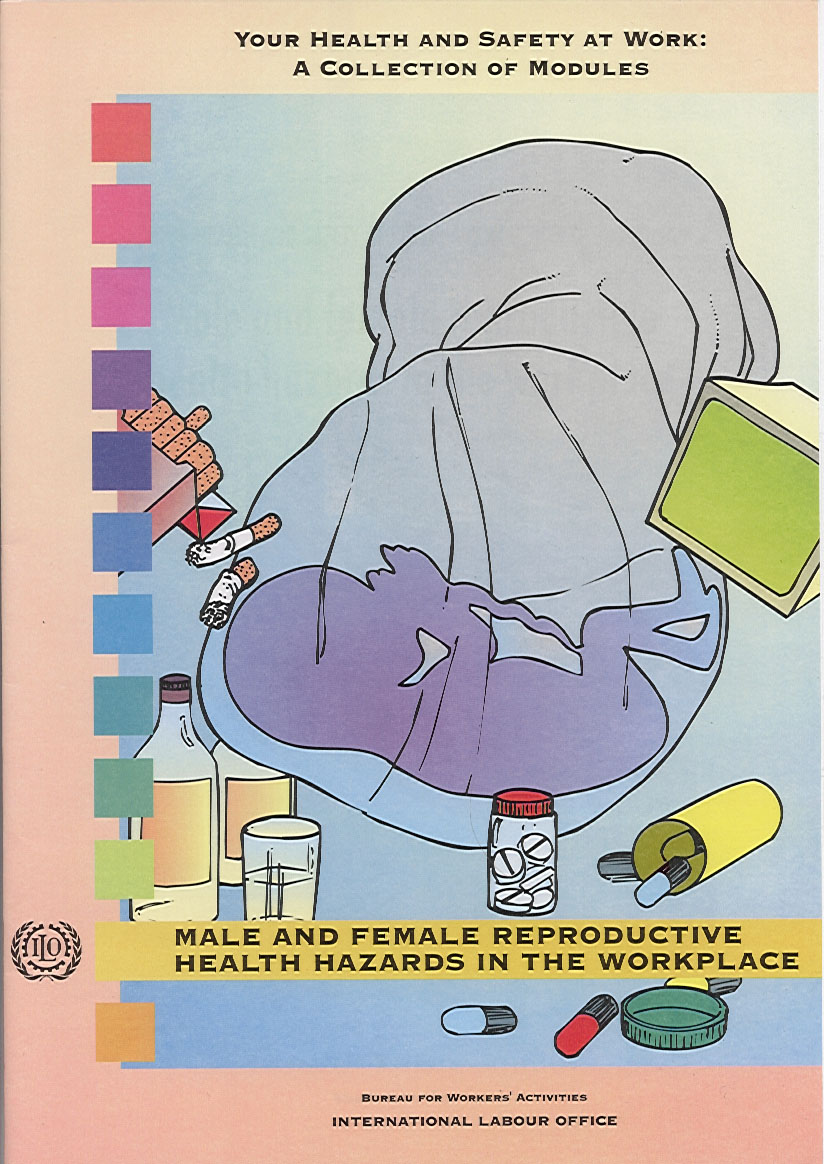

MALE AND FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH HAZARDS IN THE WORKPLACE

Goal of the Module

This Module provides trainees with background information on how occupational hazards can affect the reproductive systems of both men and women. Topics discussed include: when and how reproductive damage occurs, what kinds of reproductive health problems can occur, how a worker can tell if a chemical or work situation is hazardous to his or her reproductive health, how workers are protected, and the role of the health and safety representative.

| Objectives | |

|

At the end of this Module, trainees will be able to: (1) explain when reproductive damage may result from workplace exposures; (2) describe several kinds of reproductive health problems that can occur from exposure to occupational hazards; (3) suggest several ways of protecting workers from reproductive harm. |

What is in this Module

Thousands of hazardous chemicals are produced and used in a wide variety of workplaces, all over the world. Some of these substances can have negative effects on the reproductive health of both male and female workers who are exposed to them. There are also a variety of physical and biological agents (such as radiation and bacteria) used in many workplaces that expose workers to additional reproductive hazards. Additionally, there are many work situations (such as work which is highly stressful, or shift work) that may cause negative effects on the reproductive systems of male and female workers.

To date, most chemical substances and work situations have not been studied for their potential to have damaging effects on the human reproductive system. Despite the lack of information about possible reproductive health effects, many substances are still used in a variety of workplaces.

Many workers are exposed to such hazards everyday at work. Working with particular substances or under certain work situations may cause some workers to experience abnormalities in their sexual or reproductive health. Many workers may not know that such problems can be related to occupational exposures. While the information is minimal, much of what is known about the effects of workplace substances on male and female reproductive systems has been learned, in fact, by studying exposed workers, their spouses and children.

It is important that workers and trade unions learn as much as possible about the substances used in their workplaces, when information does exist. Protective measures should be implemented to ensure that pregnant workers and workers (male or female) who may be planning to have a child are not exposed to known or suspected reproductive health hazards.

Note: If you find some of the terms used here new to you, please check in the glossary at the back of this Module for definitions.

Reproductive system |

|

|

Points to remember |

|

|

II. When and how does reproductive damage occur?

Exposure to certain hazardous substances or hazardous work conditions can affect reproductive health before or after conception takes place. Some occupational hazards, particularly certain chemicals and radiation, can seriously affect a developing embryo or foetus (also written fetus). Appendix I at the back of this Module gives some examples of chemicals that are known to have negative effects on sexual behaviour and reproduction.

Adverse effects due to exposure can also occur after birth, affecting the development of a baby or child. While these effects are not considered reproductive hazards, it is important to know that newborns and children are particularly vulnerable to the effects of hazardous substances.

Some workplace exposures can prevent conception. Exposure to certain substances or combinations of substances can cause changes in the sex drive of either men or women, damage to the eggs or sperm, changes in the genetic material carried by the eggs and sperm, or cancer or other diseases in the reproductive organs of men or women.

Some mutations may cause only minor changes in a child. Other changes may not produce any visible effects at all. However, it is important to remember that although there may not be visible effects of damage in a child, the changes in genetic material are permanent. These permanent changes may be passed on to that child's future offspring, where visible changes may be seen.

A substance that causes changes in genetic material is called a mutagen. There are special laboratory tests which can identify substances as mutagens. Often substances are tested on animals to see if mutations occur.

Make a list of mutagens used in your workplace. This can be done by making a list of the generic names of chemicals you use and checking them against Appendices I and VI at the back of this Module. Most cancer-causing chemicals (except most solvents) are mutagens. |

|

Once fertilization has taken place, some harmful substances can pass through the mother to the developing embryo or foetus. The foetus is generally thought to be at greatest risk during the first 14 to 60 days of the pregnancy, the time when the major organs are being formed. However, depending on the type and amount of exposure, a foetus can be harmed at any time during the pregnancy. For example, exposure to a particular substance at one point in a pregnancy may result in organ damage, but exposure to the same substance at another time in the pregnancy could cause miscarriage.

It is important to remember that the normal incidence of miscarriage and birth defects varies from country to country. When birth defects or miscarriages occur, local norms should be taken into consideration; however, any case which is, or may be, related to workplace exposure should not be ignored.

A substance that prevents the normal development of a foetus is called a teratogen. Teratogens can pass from the blood of the mother to the blood of the foetus, across the placenta. Many people may be familiar with thalidomide, a drug which was used to prevent nausea during pregnancy. Thalidomide is now known to have teratogenic effects. However, this fact was not known when it was first used and as a result, thousands of children were born with deformed or missing limbs because their mothers took this drug during pregnancy. Fortunately, tests are now in place to detect the effects of drugs before they come on the market.

The umbilical cord carries the blood of the foetus to the placenta where it passes close to the blood of the mother and nutrients and wastes are exchanged. It is in the placenta that teratogens can be passed on to the embryo or foetus. |

|

Teratogens are toxic chemicals which can pass from the blood of the mother to the blood of the foetus, where they can have an adverse effect on the development of the foetus. |

|

There are a number of chemicals, biological agents (such as bacteria), and physical agents (such as radiation) used in a variety of workplaces that are known to cause birth defects. (Appendix VII at the back of this Module gives some examples of substances that have been observed to cause adverse reproductive outcomes if exposure occurs during pregnancy. It is important to note, however, that adverse reproductive outcome may or may not include birth defects.) Birth defects can include a wide range of physical abnormalities, such as bone or organ deformities, and behavioural or learning problems such as mental retardation.

In some cases, factors that cause stress, such as repetitive work, lack of breaks and constant demands on pregnant workers, can be directly related to premature births.

Cigarettes, medicines, alcohol, radiation and stress may have bad effects on a developing foetus. |

|

Other factors can also affect the health of a developing foetus, such as stress at home, smoking cigarettes, drinking alcohol, or taking certain drugs and medications. Additionally, these factors can combine with hazardous work situations and increase the dangers to a foetus even more. Pregnant workers who are exposed to certain chemicals, radiation or stress factors at work are also at risk of giving birth to babies with lower than normal birth weight. This can lead to physical and mental development problems.

Occupational exposures can also harm a developing child even after it is born. While this is not directly related to reproductive health, it is important to know that newborns and children are particularly vulnerable to the effects of chemicals or other harmful substances that may be brought into the home on clothing, shoes or even skin and hair. For example, it is well documented that children with long-term exposure to asbestos brought home on clothing have an increased risk of developing asbestos-related lung diseases. Breast milk is another route of exposure for babies. If harmful substances are present in breast milk, then infants can take in those substances while breast-feeding.

Reproductive hazards to men and women

Source: A. Hricko, M.

Brunt: Working for your life: A woman's guide to job health hazards,

joint publication of Labour Occupational Health Programme and Public Citizens'

Health Research Group, Berkeley, California, 1976.

|

Points to remember about |

|

|

III. How can you know if a

chemical, biological agent,

physical agent, or work situation is hazardous

to your reproductive health?

It is very difficult to know exactly which chemical, biological or physical agent, or work situation in a workplace will have negative effects on the reproductive health of male or female workers. Unfortunately, most chemicals, biological or physical agents, and work situations have not been adequately studied for their possible effects on human health and reproduction. In fact, many substances used in a variety of workplaces have not been studied at all.

There are several important factors that determine whether exposure to a chemical, biological or physical agent, or other type of work situation will have negative effects on a worker's health. These factors are:

As a general rule, a worker should assume that regular exposure to any chemical or biological agent is potentially hazardous to his or her reproductive health and to his or her health in general.

Workers and unions should work together with employers to eliminate hazardous exposures altogether, or at least to reduce them to the levels permitted in national or internationally recognized standards, if they cannot be eliminated.

Information about the potential reproductive health effects of occupational hazards is gradually being collected. However, to date, the information that is available about many substances used or produced in many workplaces is still insufficient. Where it is known that exposure to a particular hazard (or combination of hazards) can have an effect on the foetus, no pregnant woman should be exposed to that hazard at all. However, workers and unions should ensure that actions taken or policies implemented to protect workers do not result in discrimination against women workers.

Employers should provide workers with detailed education about any potential hazards with which they work. Workers should be informed about the known hazards of specific chemicals and combinations of chemicals, the recommended exposure limits, and the recommended methods of protection. (For more detailed information see the Modules Chemicals in the workplace and Controlling hazards in this collection).

Education about reproductive health and potential hazards in the workplace is important for all workers. |

|

|

Points to remember about knowing whether a |

|

|

IV. Protecting your reproductive health

To protect the reproductive health of all workers, exposure to chemicals, radiation, biological agents, and stressful working conditions should be eliminated or at least reduced as much as possible. Mutagenic, teratogenic and carcinogenic substances should be completely eliminated or isolated from every worker and from the work environment.

There have been several general approaches taken by some industries to address the issue of protecting workers' reproductive health from workplace exposures. However, many of these approaches are undesirable and are in fact discriminatory.

Allowing workers to be exposed to reproductive health hazards without control or concern is, of course, the most undesirable approach.

Exclusionary policies

Many industries have taken some type of action to protect workers. Often this action is to refuse work to or transfer the workers they consider most susceptible to reproductive hazards, who happen to be women of childbearing age. (It has often been argued that such policies are not designed to protect the worker but are designed to protect the employer from possible future lawsuits.) Policies excluding women from certain jobs are often not applied consistently or uniformly. For example, exclusionary policies are applied in jobs that traditionally have been closed to women anyway, while excluding women from certain jobs is not a policy in industries where women have always been and still are important members of the workforce. In such industries women often are employed despite the potential for exposure to reproductive hazards. For example, although X-ray technicians, beauticians, dry cleaners and launderers, and surgical operating room personnel are exposed to substances that can affect reproduction, women are generally not excluded from these jobs.

One of the biggest problems with exclusionary policies for women is that while they discriminate against fertile women through denial of, or removal from certain jobs, fertile men are still exposed in the same jobs. It is vital that attention also be given to the reproductive problems that affect men. Unfortunately, the effects of hazards on male reproduction have not been well studied to date.

Transfer policies

Some industries have implemented transfer policies that allow women workers to move out of areas with possible exposures when they are pregnant or thinking about becoming pregnant. Such policies can be a sound option until the workplace can be made safe for reproductive health or when hazards cannot be eliminated. However, transfer policies should also be designed to protect men who are planning a child.

If transfer policies are adopted, they should be accompanied by rate retention and with no loss of seniority in position. Rate retention guarantees that the worker is not penalized for becoming pregnant or expressing a wish for protection while planning a child by being forced to move to a job that pays less. Similarly, after the pregnancy, the worker should have the right to have his or her old job back.

The unfortunate reality in many workplaces is that fertile or pregnant women are simply dismissed instead of being given alternative, non-hazardous work. Since her family usually depends on her income, a pregnant or fertile worker often has no alternative but to stay in a job, even at the risk of exposing herself or her unborn child to hazards, when no other job is made available to her. Such a choice is no choice at all for any worker. In the case of male workers, the same applies, although in the latter instance the risks are less “visible” and therefore tend to be minimized.

There is no single answer to solving the problem of reproductive hazards in the workplace and the exclusion of certain groups of workers. In many countries, unions, public interest groups, scientists and government representatives have been fighting these issues for many years. Although some countries have made progress through the establishment of laws, regulations and government agencies, much more needs to be done to ensure the complete protection of all workers' reproductive health.

What needs to be done?

More research is needed on substances and job conditions that are known or suspected to affect reproduction so that adverse effects can be identified and preventive measures adopted.

Governments have a responsibility to take action. They should:

Workers, health and safety representatives, and trade unions also have a responsibility to take action. They can:

Workers and their unions must work towards ensuring that each workplace is a healthy and safe place to work. Only in this way will workers be able to have confidence that exposures in the workplace will not harm their own reproductive health, or the health of their children — born or unborn.

Keeping a record and holding group discussions can help to detect abnormal patterns of sexual behaviour and problems with the reproductive system. |

|

|

Points to remember |

|

|

V. Role of the health and safety representative

As health and safety representative you can play an important role in helping to ensure that work does not jeopardize the reproductive health of any worker — male or female. Your efforts in the areas of worker education, workplace policy development and implementation, monitoring of substances and work conditions, and record-keeping will help to achieve this objective. Here are some steps to help you reach your goals:

Health and safety representative |

|

Work together with the union and the employer to eliminate exposures that are known or suspected to have health effects including reproductive health effects.

Employers should provide workers with detailed information and health and safety training about the chemicals, physical or biological agents, or any other potentially hazardous substances or work situations with which they must work. There are a variety of ways to get information on substances and work situations that may be potentially hazardous to reproductive health. The Module Chemicals in the workplace contains a number of detailed recommendations on this point.

Encourage workers to keep a record of their work conditions, as well as the names of any chemicals, biological or physical agents, and potentially hazardous situations to which they may be exposed. They should note any irregularities or abnormalities that occur in their sexual functioning, in their menstrual cycle, in their (or their partner's) ability to become pregnant, or in their children's development.

Note: It is important that health and safety representatives are informed about any problems that exist. However, you should be aware that these are sensitive areas for workers to discuss. Many workers will not want to discuss issues related to their sexual functioning, menstrual cycle, ability to conceive, etc. Therefore you will need to determine appropriate methods of gathering information on these delicate issues, taking into consideration the workforce and local customs.

Encourage workers in similar jobs to meet and discuss any work situations that could be dangerous to their health. Any health problem common to two or more workers should be reported and acted on as soon as possible.

Work together with the union and employer to develop and implement policies that allow pregnant workers to transfer for the duration of the pregnancy from work known or suspected to have reproductive health effects. Similar protection should be extended to workers (male and female) who are planning a child.

Work to eliminate or prevent discriminatory practices against hiring certain workers, such as women of childbearing age. A workplace that is safe for all workers is a preferable alternative to refusing to hire certain workers because the work may be dangerous to their reproductive health.

Work together with your union and employer to ensure that workers have facilities where they can wash after work. This will help to prevent bringing hazardous agents home.

| VI. Summary | |

|

|

|

Exercise.

A case of negative male fertility outcome due to chemical exposure at work Source: Occupational health, edited by Barry S. Levy and David H. Wegman, Little, Brown and Company, Boston/Toronto, 1983. Note to the instructor The following is a true case description of the best-documented epidemic of occupational reproductive problems in males. This case was documented in the United States in 1977 among male pesticide production workers. For this exercise, you may want to have a flipchart (or large pieces of paper taped to the wall) and markers or a chalkboard and chalks. Instructions Read the case out loud to the class. Ask the participants to write down key points in the case as you read it to them. When you have finished reading the case, ask the participants to work in small groups of three to five people to discuss the case. Ask the groups to come up with ideas on how they think the case could have been handled once it was realized that the chemical DBCP was the cause of the fertility problems. There are a number of questions following the case which the groups may want to think about and discuss. Groups should discuss their responses with the whole class. You can note the main ideas of each group on the flipchart or chalkboard. There are no right or wrong answers to the questions that follow; they are simply for discussion purposes. After the class has discussed all of the groups' ideas, then read the last paragraph of the case-study to the class. Last paragraph of case-study Action taken Based on the findings of this case, the use of DBCP — but not its manufacture — was banned by the Environmental Protection Agency in the continental United States (it is still used in Hawaii). The only other pesticide found so far to have similar reproductive effects in males is kepone (chlordecone). The case A 30-year old pesticide production worker went to his physician complaining that despite attempts to have a second child his wife had failed to become pregnant. His medical examination showed that there was no sperm in his semen. A medical examination of his wife did not show anything unusual. The worker informed his physician that he was exposed to more than 100 chemicals at work. The physician felt that he (the physician) did not have the expertise or time to evaluate the chemical exposures. When the worker started discussing his problem with his co-workers, he learned that there were also other couples who had also been unable to have children. After discussing the problem with his co-workers, the worker finally convinced five co-workers to volunteer to submit semen samples for analyses. The analyses revealed that all five men had few or no sperm at all. These results were sent to another physician who had previously been a consultant to the local trade union. The physician, who had not seen the men before, examined them and repeated the semen analyses. The results were the same. Further tests were performed on the testes of several of the affected workers. The results indicated that the absence of and the low number of sperm in the affected workers were direct effects of exposure to toxic chemicals in the workplace. Of the 100 chemicals used in the plant, four had been shown in animal studies to be toxic to the male reproductive system. Since 1,2,-dibromo-3-chloropropane (DBCP) was produced in the plant in the largest amounts, it was suspected to be the cause of the men's reproductive health problems. Two other plants that produced DBCP evaluated their workers and found similar results. The association between the fertility problems and exposure to DBCP was strengthened when it was found to be the only chemical exposure that workers at all three plants had in common. Questions

|

Source: Health hazards in the electronics industry, International Metalworkers' Federation, Asia Monitor Resource Centre, Hong Kong, 1985.

conception: the moment at which an ovum is fertilized by a sperm and begins to grow; the beginning of a new life; the beginning of a pregnancy. |

menstrual cycle: a fertility cycle lasting on the average 28 days and controlled by secretion of certain hormones in a woman's body. The cycle begins with a two- to five-day period of menstruation (discharge of blood and uterine lining) followed on or around the 14th day (midpoint) by the release of an egg (ovulation) which travels from one of the ovaries along the fallopian tube to the womb (uterus) where it remains for about a week. If the ovum has not been fertilized by a man's sperm during the few days following ovulation, hormone changes bring about menstruation and a new cycle. |

congenital: describes a problem present or occurring at birth. |

|

embryo: an unborn child from the time of conception until the end of its eighth week of growth in the womb, after which time it is called a foetus until the time of its birth. |

|

foetus: an unborn child after it has developed from its embryonic stage, that is, following the eighth week from the time of conception. |

mutagen: an agent, such as certain chemicals or ionizing radiation, that can bring about a mutation; there are about 2,000 known or suspected mutagens. |

gene: a sequence of “DNA” (deoxyribonu - cleic acid) which, as a single functional unit, carries a specific code which determines how a cell grows. Thus it is the genes of each cell which transmit hereditary characteristics or “traits”. Genes can be damaged (mutated) or destroyed by certain chemicals and by ionizing forms of radiation. DNA alone or in combination with other molecules constitutes a target for cell killing. Because DNA contains genetic information vital to the life of daughter cells, radiation damage to DNA is a key factor in cell death. |

mutation: an irreversible change in a chromosome or a gene structure in a cell caused by a foreign chemical substance or ionizing radiation. This change usually has a negative effect on cell growth and function. Sex cells (sperm or ova) damaged by a mutagen can transmit undesired traits to offspring for an indefinite number of generations. |

ova: female reproductive cells present at birth and normally released one at a time monthly by the ovaries; eggs; (singular, “ovum”). |

|

sperm: male reproductive cells produced continuously in the testes; “seed”; spermatozoa. |

|

teratogen: a toxic substance which is capable of being transported across the placenta from the bloodstream of the mother to the bloodstream of the embryo or foetus and causing miscarriage, congenital birth defects or illness. |

Appendix I. Chemicals that have toxic effects on reproduction

The following list is of substances used or occurring in electronics which threaten the ability of both men and women to have a normal sex life and to have normal children.

Source: Health hazards in the electronics industry, International Metalworkers' Federation, Asia Monitor Resource Centre, Hong Kong, 1985.

| Chemical name | Teratogen | Reduced fertility or sterility | Miscarriage or fetal death | Birth defects, mutations, fetal damage | Cancer of reproductive organ | Menstrual problems |

| Acrylonitrile | A | ? | ||||

| Antimony | A | HA | H | ? | H | |

| Arsenic | H s | H | A | H | ||

| Benzene | A | H si | A | ? | H | |

| Cadmium | H A si | H | H | H | ||

| Carbon dioxide | HA | H/A | ||||

| Carbon disulfide | H A si | H/A | H A | |||

| Carbon monoxide | H si | A | ||||

| Carbon tetrachloride | A | ? | ||||

| Cellosolve chlorinated hydrocarbons H/A ? (several kinds) |

H/A | ? | ||||

| Chlorobenzene | A | A | ? | |||

| Chloroform | A | ? | ||||

| Diglycidyl ether | A | ? | ||||

| Dimethyl formamide | A | |||||

| Epichlorohydrin | H A s | ? | ||||

| Ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid | A | |||||

| Ethylene dibromide | H A s | H/A | H/A | ? | ||

| Ethylene dichloride | H | H | H | ? | ||

| Ethylene oxide | A | A | ? | |||

| Ethylidene chloride | A | |||||

| Freon 31 (chlorofluoromethane) |

A | |||||

| Lead | H A si | H | H | ? | H | |

| Lithium | A | |||||

| Manganese | H si | ? | ||||

| Mercury | H A si | H/A | H/A | |||

| Methyl ethyl ketone | H | |||||

| Methyl methacrylate | A | |||||

| Methylene chloride | H | |||||

| Nickel | A | ? | ||||

| Nitrous oxides | H/A | H/A | ||||

| Perchloroethylene | A | ? | ||||

| Phosphorus | H s | |||||

| Polychlorinated biphenyls | A | H | H | ? | ||

| Selenium | A | |||||

| Telludum | A | |||||

| Toluene | A | A | H | |||

| 1,1,1-trichloroethane | A | A | ||||

| Trichloroethylene | H si | H | H A | ? | ||

| Vinyl chloride | H | H | H | H/A | ? | |

| Xylene | A | A | H | |||

| Zinc chloride | A | ? | ||||

| Radiation | H A | H A | H A | H | ||

| Rotating shifts | H |

H = evidence for humans, A= evidence for animals, H/A= evidence for humans and for animals, s = reported to cause sterility in men, i = associated with male impotence, ? = known to cause cancer in other parts of the body

Sources for Appendix I

Sources for Appendix I. (Cited in primary source).

Chemical Hazards to Human Reproduction, Washington, DC, Council on Environmental Quality (U.S. Government), January 1981.

Dapson, et al: “Effect of methyl chloroform on cardiovascular development in rats”, in Teratology, Vol. 29, No. 2, April 1984, p. 25A.

1979 Registry of toxic effects of chemical substances, Volumes 1 and 2, Publication No. 80-111, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 1980.

Guidelines on Pregnancy and Work, Publication No. 78-118, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, 1978.

“Reproductive hazards in the electronics industry”, in Factsheet No. 2, Project on Health and Safety in Electronics, 1979, Santa Clara, California.

Plunkett, E.R., et al: Occupational diseases: A syllabus of signs and symptoms, Barrett Co., Stamford, Connecticut, 1977.

Stellman, J.: “The effects of toxic agents on reproduction”, in Occupational Health and Safety, pp. 37-43, U.S.A., April 1979.

Appendix II. Reproductive hazards to men and women

Source: Clinical occupational medicine, by L. Rosenstock and M.R. Cullen, W.B. Saunders Company, London, 1986.

Hazard |

Outcome |

Proven reproductive hazards (based on human studies) |

|

Anesthetic

gases |

Miscarriage,

death of newborn |

Suspected reproductive hazards (based on human studies) |

|

Carbon

monoxide |

Slowed

growth |

Suspected reproductive hazards (based on animal studies) |

|

Acrylonitrile |

|

Appendix III. Chemical reproductive hazards affect both men and women

Source: Clinical occupational medicine, by L. Rosenstock and M.R. Cullen, W.B. Saunders Company, London, 1986.

Occupational factors proven to harm sperm |

Chemicals |

Carbaryl |

Other |

Heat |

Chemicals suspected of harming sperm* |

Arsenic |

Appendix IV. Industries with a reported increased risk of adverse reproductive outcome in exposed women, without linkage to specific exposures

Source: Preventing occupational disease and injury, edited by J.L. Weeks, B.S. Levy, G.R. Wagner, American Public Health Association, Washington, DC, 1991.

Industry |

Reported Outcome |

Rubber

industry |

Spontaneous

abortion |

Appendix V. Examples of agents toxic to the male reproductive system

Source: Environmental and occupational medicine, edited by W.N. Rom, Little, Brown and Company, Boston, 1983.

| Chemical hazards | Species effect observed (h = humans, a = animals) |

Examples

of occupations |

| Alcohol | h | Social hazard |

| Alkylating agents | h, a | Chemical and drug manufacturing |

| Anesthetic gases nitrous oxide |

a, h | Medical, dental and veterinary workers |

| Cadmium | h, a | Storage batteries; smelter workers |

| Carbon disulfide | h, a | Viscose rayon manufacture; soil treaters |

| Carbon tetrachloride | a | Chemical laboratories; dry cleaners |

| Diethylstilbesterol (DES) | a, h | DES manufacturers |

| Chloroprene | h, a | Rubber workers |

| Ethylene oxide | a, h | Health care workers (disinfectants), users of epoxy resins |

| Hair dyes | a | Cosmetic manufacturers, hairdressers and barbers |

| Lead | h, a | Storage batteries, policemen; smelter workers |

| Manganese | h | Welders, ore smelters and roasters |

| Nickel | a | Smelters, welders |

| Organic mercury compounds |

a | Pesticide workers |

| Tris (flame retardants) | a, h | Clothing and textile work |

| Pesticides | a, h | Farmworkers; pesticide manufacture, applicators |

| Dibromochloropropane | (DBCP) | Exterminators |

| Kepone | ||

| DDT | ||

| Carbaryl | ||

| DDVP | ||

| Malathion | ||

| Vinyl chloride | h | Polyvinylchloride manufacture and processing |

| Physical hazards | ||

| Elevated carbon dioxide | a | Brewery workers; chemical manufacture |

| Elevated temperatures | h, a | Bakers; glassblowers; foundry and oven workers |

| Microwaves | h, a | Radar operators; air crewmen; transmitter operators |

| X-irradiation | h, a | Health workers; radiation workers |

Appendix VI. Carcinogenic chemicals in electronic manufacturing

Source: Health hazards in the electronics industry, International Metalworkers Federation, Asia Monitor Resource Centre, Hong Kong, 1985.

This is a partial (not complete) list of chemicals used or occurring in electronics manufacturing which, according to medical experts, are known or suspected to cause cancer in humans or animals.

| Chemical | Humans | Animals |

| Acrylonitrile Antimony Aromatic amines (dyes ) Arsenic (and compounds) Arsine Asbestos Benzene Bensidine Benzyl chloride Beryllium (and compounds) Bis(chloromethyl)ether Boric acid Cadmium (and compounds) Carbon tetrachloride Chlorinated diphenyls Chlorinated hydrocarbons Chloroform Chlorotoluene Chromates Chromic acid Chromium (and compounds) Cobalt Dichlorobenzene 3,3'dichlorobenzidine (and salts) a,a-dichloromethyl ether Diepoxy butane Diethyl amine Diglycidyl ether Diglycidyl ether of bisphenol A 1,4-dioxane Diphenyls Epichlorohydrin Ethyl acrylate Ethyl alcohol* Ethylene dibromide Ethylene dichloride Ethylene imine Ethylene oxide Fibreglass (crystalline) Formaldehyde Gold Isopropyl alcohol*** Lead (and compounds) Maleic anhydride Manganese Methyl methacrylate Moca Molybdenum trioxide Nickel (and compounds) Perchloroethylene Phenol Platinum Polychlorinated biphenyls Polymers (plastics): Polyethylene Polystyrene Polytetrafluoro-ethylene Polyurethane Polyvinyl chloride (dust) Propyl alcohol Radiation: Microwaves Radioisotopes Ultraviolet light X-rays Selenium (and compounds) Silica; quartz (crystalline) Silver Styrene Styrene oxide Tetrafluoroethylene Titanium dioxide 1,1,1 trichloroethane Trichloroethylene Triethylene glycol diglycidyl ether Zinc chloride |

Yes S Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes S S Yes S Yes S S S S S Yes Yes Yes S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S Yes S S S S S S S S S Yes Yes Yes S S S S S S S S S |

Yes S Yes S S Yes S Yes Yes Yes Yes S Yes Yes S S Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes S Yes S Yes Yes S Yes Yes S Yes S Yes Yes Yes Yes S S Yes S** S Yes S S S Yes Yes Yes S S S** Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes S Yes S Yes Yes Yes S S** S** S S S S S Yes Yes S |

Yes = sufficient proof of

causing cancer; S = SUSPECTED of causing cancer. (Note: SUSPECTED means either that there

is some evidence but not enough for conclusive proof, or that since there is some evidence

of cancer in animals we must suspect there is also a cancer risk for humans.)

* probably due to contaminants which may act as co-carcinogens.

** by implant only.

*** manufacture of isopropyl alcohol is a definite cancer risk for humans.

Appendix

VII. Examples of substances observed to induce adverse

reproductive outcomes following exposure

during pregnancy

Source: Environmental and occupational medicine, edited by W. N. Rom, Little, Brown and Company, Boston, 1983.

| Substance | Occupations where exposure may occur |

| Alkylating agents | Drug workers |

| Anaesthetic gases* | Operating room personnel (including dental and veterinary workers) |

| Arsenic | Agricultural workers |

| Benzene | Chemical workers, laboratory technicians |

| Carbon monoxide | Outside workers, offices with smokers |

| Chlorinated hydrocarbons | Laboratory workers, craft workers |

| Diethyl stilbesterol* | Drug workers |

| Dimethyl sulfoxide | Laboratory workers |

| Dioxin* | Agricultural workers |

| Infectious agents | Health care workers, social workers, teachers, animal handlers, meat cutters |

| Rubella virus* | inspectors, laundry workers |

| Cytomegalovirus | |

| Herpes virus hominis | |

| Toxoplasma | |

| Syphilis* | |

| Ionizing radiation* | X-ray technicians and technologists, atomic workers, drug workers |

| Organic mercury compounds |

|

| Organophosphate | Agricultural workers |

| pesticides | |

| DFP | |

| Parathion | |

| Captan | |

| Carbaryl | |

| Theram | |

| Polychlorinated biphenyls* | Electrical workers, microscopists (immersion oil) |

* Human effects noted